10 Ways Earth Changed Forever in 2018

How Earth Changed in 2018

Earth is always changing, and 2018 — a year filled with hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes — was no exception. Here are 10 ways Earth changed these past 12 months.

Kilauea's Eruption

Kilauea's stunning 2018 eruption was its largest in at least 200 years, according to a 2018 report in Science magazine . From late April to early August, the Hawaiian volcano spewed out enough lava to fill 320,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. The lava covered about 13.7 square miles (35.5 square kilometers), scorching Hawaii's Big Island and adding over a square mile (2.5 square km) of land off the coast.

The volcano's lava evaporated an entire lake, left glass strands known as Pele's hair around the island and even created a new island off the coast. [Read more about the Hawaii eruption]

New Zealand's moving islands

New Zealand's South Island is now more than a foot closer to its North Island, researchers learned in 2018. The catalyst was the magnitude-7.8 earthquake that shook the nation in 2016. Since then, the Earth's crust has continued to shift, which is why the two islands have moved nearly 14 inches (35 centimeters) closer to each other than they were before the earthquake. [Read more about the moving islands]

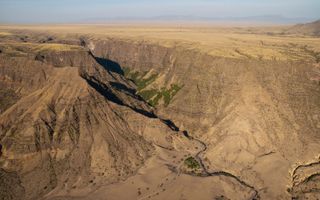

Africa's Great Rift

The Great Rift Valley in East Africa has been on the move for millions of years. Even so, an enormous crack that appeared in southwestern Kenya in March completely surprised people when it split across a busy road and tore houses in two. The gaping, 50-foot-long (15 meters, and still growing) hole appeared on March 19, following a period of heavy rains and seismic activity. The chasm is part of a much larger process that will split East Africa from the rest of the continent in tens of millions of years, thanks to the busy tectonic plates in the region. [Read more about the unexpected split]

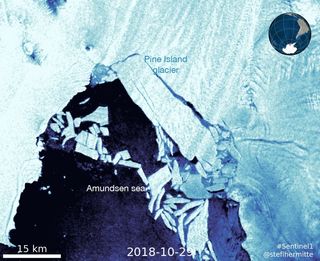

Goodbye, glacier

In October, an iceberg about five times the size of Manhattan broke off of Pine Island Glacier in Antarctica, merely a month after a crack appeared. At 115 square miles (300 square kilometers), the iceberg is even larger than another iceberg that broke off Pine Island Glacier in 2017. Pine Island Glacier is calving icebergs a lot more frequently than it used to. While these bergs used to lop off the glacier about once every six years, now every other year, or even every year, one will calve.

It's unclear why this is happening, but climate change may be a factor, said Stef Lhermitte, an assistant professor in the Department of Geoscience and Remote Sensing at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. [Read more about the giant iceberg]

California wildfires

California had more than its fair share of devastating wildfires this year. Its most deadly in history, the Camp Fire, raged from Nov. 8 until its containment on Nov. 25. It burned 153,336 acres (620 square kilometers) and led to the deaths of 86 people. The Camp Fire, along with others in the state this year, such as the Carr, Woolsey, Hirz and Mendocino Complex, also killed countless wildlife, including a mountain lion that had survived the Woolsey Fire.

Breathing in smoke from these fires is bad for human health, and so doctors asked people (even healthy folks) to stay inside. [See photos of these destructive fires]

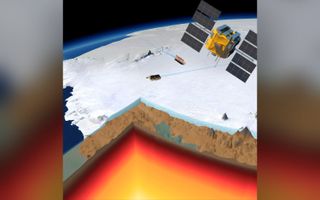

Antarctica inching upward

Teenagers aren't the only ones having growth spurts. Bedrock under Antarctica is also rising — about 1.6 inches (41 millimeters) annually, researchers learned in 2018. This growth rate, the fastest for the continent on record, is likely due to Antarctica's thinning ice.

As vast quantities of ice melt, the continent is less weighed down. This is both good and bad. It's good because this uplift could make the remaining ice sheets more stable. But the bad news is that the rising Earth likely skewed ice-loss estimates, meaning that scientists overestimated the amount of ice left in Antarctica. [Read more about this 'uplifting' news]

Vanishing island

A tiny island in Hawaii's Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument pulled a fast one and disappeared in October. That's bad news for the threatened Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) and the critically endangered Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi), which used the island as a nesting ground.

So what wiped out the small, 11-acre (0.04 square km) East Island? It was Walaka, an intense hurricane that reached Category 5 status with 160 mph (257 km/h) winds. [Read more about the vanishing island]

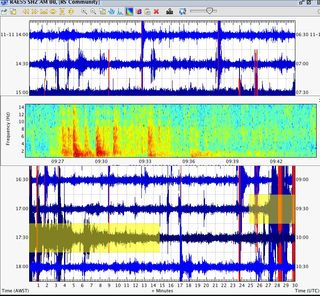

Sliding island

A seismic event on Nov. 11 off the coast of Mayotte, a small island between Madagascar and Mozambique, is filled with mystery and intrigue. For starters, it moved the island 2.4 inches (6 cm) to the east and 1.2 inches (3 cm) to the south. Then, it set off a hum that circled the world, but that nobody heard.

This hum rang at a single ultralow frequency, which is strange because seismic waves typically involve many frequencies. Scientists are still trying to figure it out. [Read more about the sliding island]

Hurricanes and typhoons galore

It was a busy year for hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones. (By the way, these are names for essentially the same thing: high winds that form over warm waters.) The 2018 season included eight hurricanes in the Atlantic, including hurricanes Michael and Florence, while the Pacific had 13 hurricanes, including Hurricane Walaka that affected Hawaii.<br>

Hurricanes Michael and Florence both dumped loads of water on the American Southeast. Florence dumped more than 20 inches (50 cm) of rain in South Carolina and 35 inches (89 cm) in North Carolina — so much that meteorologist Ryan Maue tweeted that the hurricane dropped 11 trillion gallons of rainfall in all on both states.

Gurgling, creeping mudpit

A muddy geyser carved out a huge gash in Southern California. And it's threatening the region's infrastructure like a geologic poltergeist.

These mysterious mud bubbles have created an approximately 24,000-square-foot (2,230 square meters) basin that's about 18 feet deep and 75 feet wide (5 by 23 m). And the geyser is slowly getting larger, creeping closer to railroad tracks, Highway 111 and some expensive optic cables owned by Verizon.

The geyser formed when historic earthquakes caused deep cracks underground, which allowed gases (such as carbon dioxide) to bubble upward. It was stagnant for many years, but now there's no stopping it. When Union Pacific built a giant wall out of boulders and steel, the geyser simply slipped under, and went on its merry way. [Read more about the bubbling geyser]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.