Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier Just Lost Enough Ice to Cover Manhattan 5 Times Over

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

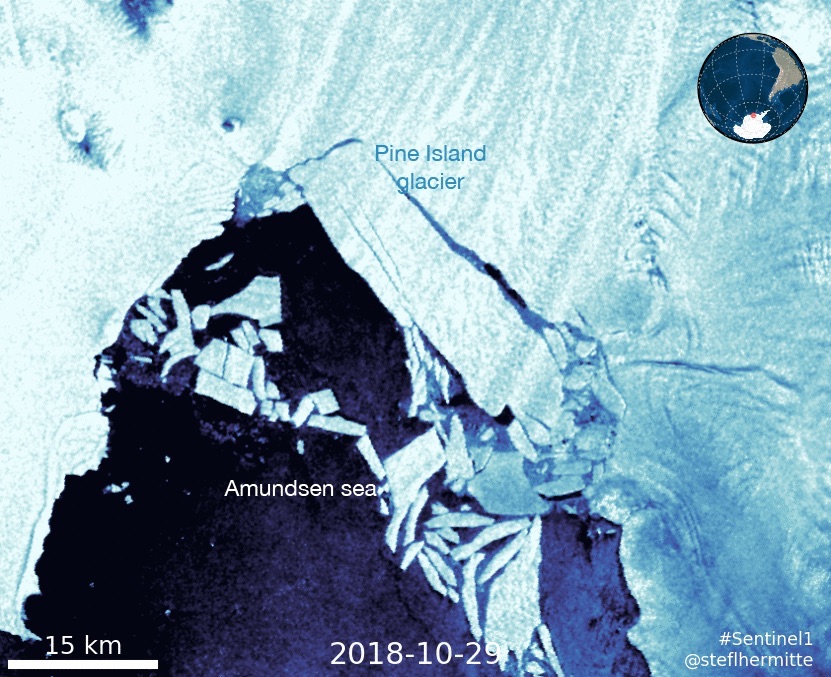

An enormous iceberg about five times the size of Manhattan broke off Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier yesterday (Oct. 29), a mere month after a crack first appeared, satellite imagery shows.

"I was a bit surprised" it broke off that quickly, said Stef Lhermitte, an assistant professor in the Department of Geoscience and Remote Sensing at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

Since spotting the crack in early October, Lhermitte had guessed that the icebergs would take weeks or months to calf, "but it turned out to be on the quick side," he told Live Science. [Photo Gallery: Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier Cracks]

At 115 square miles (300 square kilometers), the enormous amount of ice that calved off the glacier's ice shelf is even larger than the mass that broke off last year, Lhermitte said.

However, the newborn iceberg didn't stay in one piece for long. Within a day, it had splintered into smaller pieces, with the largest piece measuring a substantial 87 square miles (226 square km) before it later broke apart even more, Lhermitte said.

The biggest iceberg was large enough to receive a name, but it's not yet clear whether this will happen, given that it existed for such a short time. But, if it does get a moniker, it will likely be called B-46 by the U.S. National Ice Center, Lhermitte said.

Lhermitte first noticed the crack that led to this giant calving event while looking at an Oct. 3 satellite image. Lhermitte said he gets a satellite image of the Pine Island Glacier in his inbox every day, "and all of a sudden I saw something I didn't see the day before," he told Live Science at the time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But, after going back and looking at images from Sentinel-1, a satellite run by the European Space Agency, Lhermitte found that the crack actually appeared the last week of September, between Sept. 25 and 30. By compiling satellite images together, Lhermitte made a GIF showing how rapidly the iceberg cracked off from the ice shelf.

Even more dramatic is a time-lapse from 1972 to 2018, showing how the ice shelf has retreated over the years. It's natural for ice sheets to grow and shrink over time, as this time-lapse shows. But in 2015, the ice sheet dramatically retreated, and then continued to retreat until present day without showing any growth, Lhermitte said.

For years, the ice sheet was hitting a shallow point on the ocean floor, called a pinning point, which might have kept it from regressing too far back, Lhermitte said. "After 2015, it lost the connection with this pinning point, which could explain the retreat in 2015 and 2017," Lhermitte said. "And now this [ice shelf break] is about 5 kilometers [3.1 miles] farther inland."

Moreover, Pine Island Glacier appears to be calving icebergs more frequently than it used to. In early 2000, the glacier birthed icebergs about once every six years, with calving events happening in 2001, 2007 and 2013. But since 2013, there were four of them: in 2013, 2015, 2017 and 2018, Lhermitte said.

"The retreat we see now is outside of what we have observed [in modern times]," Lhermitte said. And that's concerning because ice shelves are key structural elements for glaciers; they slow the flow of ice into the ocean, much like dirt in a clogged drain impedes the flow of water, he said.

It's unclear exactly why Pine Island Glacier is calving icebergs more frequently than before. Warm, deep ocean water is melting the ice shelf from beneath. "That depends on climate, but this warm water getting there is also driven by how the wind patterns change," Lhermitte said. "It's very difficult to say that this is climate change because we're still figuring out how it all works."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus