'Loose Tooth' Iceberg Calves Off East Antarctica in Surprising Spot

Scientists have been watching this chunk of ice for years.

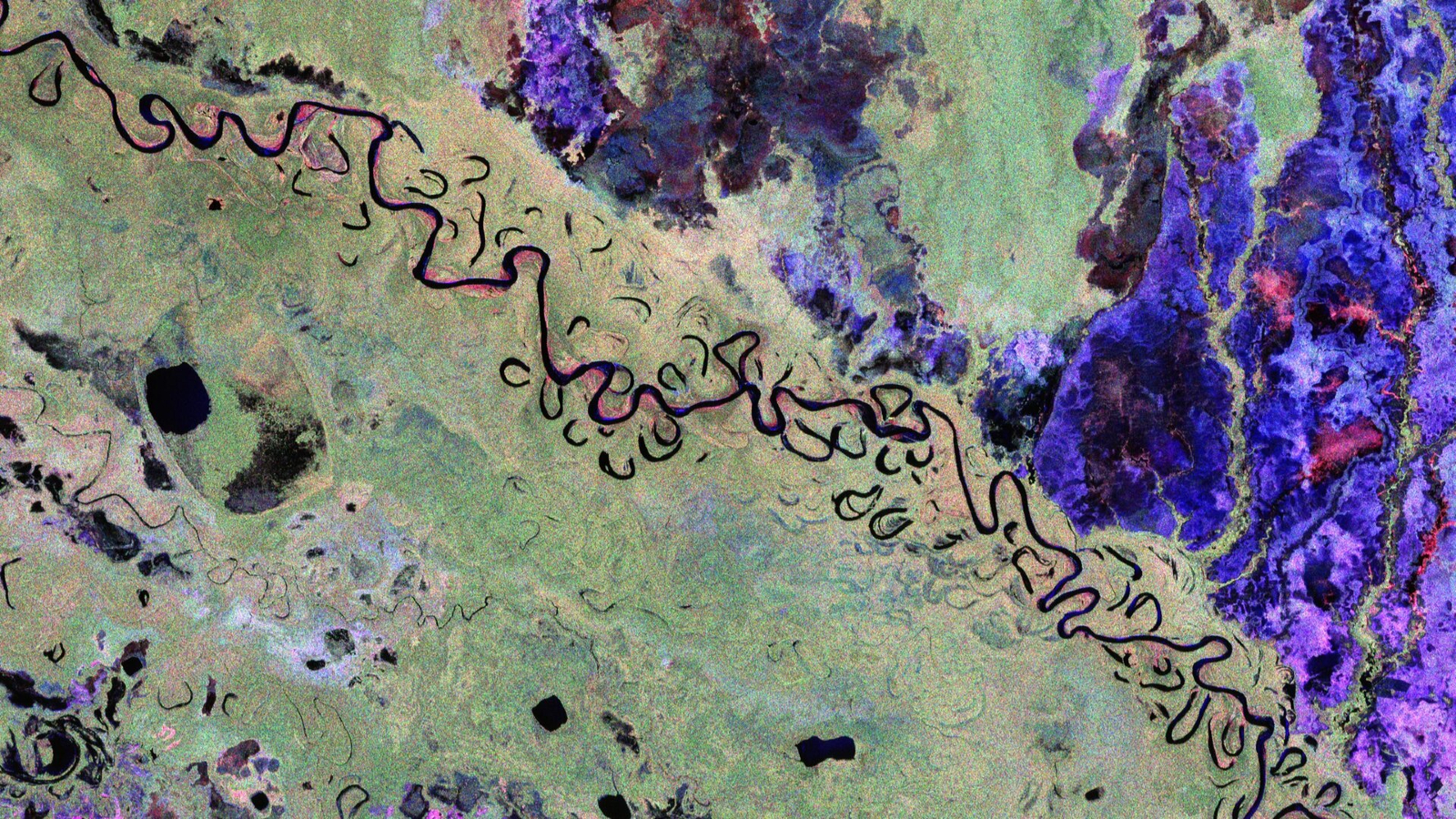

An enormous iceberg that had been hanging onto Antarctica's Amery Ice Shelf by a thread has broken free, though not precisely where scientists had expected it to rift.

The iceberg broke off the East Antarctic ice shelf on Sept. 26, ending a waiting game that had been going on for almost two decades. The 'berg broke near a spot called the "loose tooth" because the ice there is extensively cracked. It just didn't break along the rift that looked most precarious.

"We first noticed a rift at the front of the ice shelf in the early 2000s and predicted a large iceberg would break off between 2010 - 2015," Helen Amanda Fricker, a glaciologist at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. "I am excited to see this calving event after all these years. We knew it would happen eventually, but just to keep us all on our toes, it is not exactly where we expected it to be."

Related: In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time

Cracking ice

The new iceberg is 632 square miles (1,636 square kilometers) in size, approximately the size of Scotland's Isle of Skye, or large enough to cover all of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, with a little room left over. The calving appears to be part of the natural life cycle of the Amery Ice Shelf, which sheds large icebergs every 60 to 70 years, Fricker said.

"We don't think this event is linked to climate change," she said. "It's part of the ice shelf's normal cycle."

While West Antarctica has been losing ice rapidly as the global climate warms, East Antarctica has been more resilient, even gaining ice between 1992 and 2017. However, recent research suggests that this resilience could be reaching its limits. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2019 suggested that 30% of the sea-level rise from melting Antarctic ice since 1979 came from East Antarctica.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new iceberg won't contribute to sea-level rise because it was previously part of a floating ice shelf.

"The calving will not directly affect sea level, because the ice shelf was already floating, much like an ice cube in a glass of water," Ben Galton-Fenzi, a glaciologist with the Australian Antarctic Program, said in the statement. However, the research team will now be watching to see whether the ice loss allows more ocean water to penetrate under the Amery Ice Shelf, which could accelerate the loss of the ice shelf.

Antarctic retreat

Floating ice shelves act like dams, holding back Antarctica's mighty land-based glaciers and slowing their march into the sea. Current estimates peg the amount of ice lost from Antarctica at 3 trillion tons in the last 25 years, translating to 0.3 inches (8 millimeters) of sea-level rise.

That same research estimated that in Earth's previous interglacial periods, when the planet became relatively cozy and ice-free, Antarctic ice retreated at about 164 feet (50 meters) per year. It's currently shrinking at a rate of 3,200 feet (1 kilometer) per year.

The rate of ice loss is speeding up. According to a study published in January 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Antarctica lost 252 gigatons of ice each year between 2009 and 2017. (A gigaton is a billion metric tons.) Between 1979 and 1990, that rate was only 40 gigatons per year. East Antarctica is no exception, according to the study authors. East Antarctica's Wilkes Land (which is south of the Amery Ice Shelf) is of particular concern, because it hosts more ice than all of West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula.

- Photos: Diving Beneath Antarctica's Ross Ice Shelf

- Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice

- Icy Images: Antarctica Will Amaze You in Incredible Aerial Views

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus