1,300-year-old skeletons found in England had grandparents from sub-Saharan Africa, DNA studies reveal

A DNA analysis of two people who lived in Britain in the seventh century reveals they had recent African ancestry.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two people who lived in England during the Early Middle Ages had recent sub-Saharan African ancestry — likely from a grandparent, a new DNA analysis reveals.

"The DNA shows that there is human, as well as material, connection and that it extends into West Africa," study co-author Duncan Sayer, a historical archaeologist at the University of Lancashire in the U.K., told Live Science in an email.

Archaeologists discovered the burial of an adolescent girl at Updown cemetery in Kent and the burial of a young man at Worth Matravers cemetery in Dorset. Both cemeteries, located in southern Britain, were dated to the seventh century, after the fall of the Roman Empire, when Anglo-Saxon peoples occupied the island.

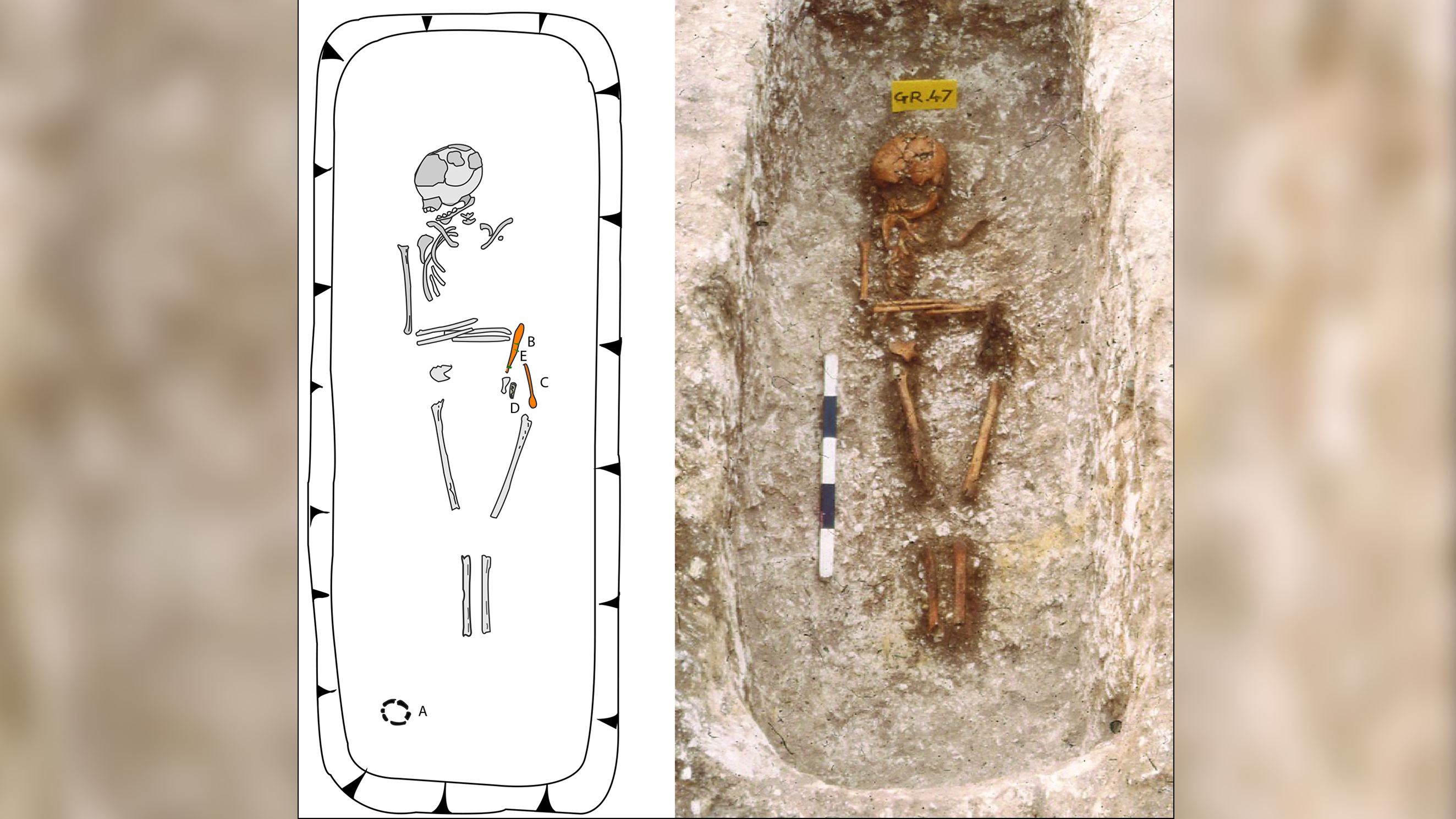

DNA analysis of five people buried at Updown and 18 people buried at Worth Matravers found that most of these individuals had Northern European or western British and Irish ancestry, researchers reported in 2022. But when they sequenced the DNA of the girl buried in grave 47 at Updown, they realized her ancestry came from an entirely different continent.

In two studies published Wednesday (Aug. 13) in the journal Antiquity, researchers detailed the unusual genetic backgrounds of the girl from Updown and the young man from Worth Matravers.

Analysis of the young people's mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mother to child, revealed that both had mothers who were likely from Northern Europe. But their autosomal DNA, which comes from chromosomes that do not code for biological sex, showed clear signals of non-European ancestry.

Related: Archaeologists discover rare liquid gypsum burial of 'high-status individual' from Roman Britain

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Both individuals thus show genetically and geographically mixed descent," and had an estimated 20% to 40% ancestry characteristic of sub-Saharan Africa, Sayer and colleagues wrote in the study. Updown girl's DNA had affinity to that of present-day Yoruba, Mende, Mandenka and Esan groups, the team found.

Based on a statistical model, the researchers propose that both people had a grandparent with African ancestry, possibly from similar groups that left sub-Saharan Africa between the mid-sixth and early seventh centuries.

The fact that these individuals were buried with their communities suggests they were valued by their peers, the authors wrote in the study.

The Updown girl was buried with a knife, a spoon, a bone comb near her left hip, and a decorated pot from Frankish Gaul at her feet. DNA analysis also revealed that she had biological relatives in the same cemetery. The Worth Matravers young man, on the other hand, was buried in a double grave with an older man he was not biologically related to.

Tracy Prowse, a bioarchaeologist at McMaster University in Ontario who was not involved in the studies, told Live Science in an email that the researchers "do a good job of discussing the historical evidence for trade between parts of Africa and northern countries."

Given previous discoveries of diverse individuals dating back to the Roman Empire — including the Ivory Bangle Lady found in York, who may have had North African ancestry — "the presence of these individuals at Updown and Worth Matravers in 7th century Britain isn't terribly surprising," Prowse said.

But Sayer does not think there is continuity between the Roman period people with African ancestry and the seventh-century people found in southern Britain. After the Germanic Vandals sacked Rome in A.D. 455, they founded a kingdom in North Africa. But then the Byzantine Empire conquered them in A.D. 534.

"At the end of the Roman period, North Africa was conquered by the Vandals," Sayer said. "It is the reconquest in the middle sixth century AD — around 533 to 535 — which seems to be the significant event here."

The DNA data showing African ancestry is "unexpected but congruent" with archaeological and historical evidence, the researchers wrote in the study, and is shedding new light on the early medieval period in Britain.

Roman Britain quiz: What do you know about the Empire's conquest of the British Isles?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus