First-ever 'superkilonova' double star explosion puzzles astronomers

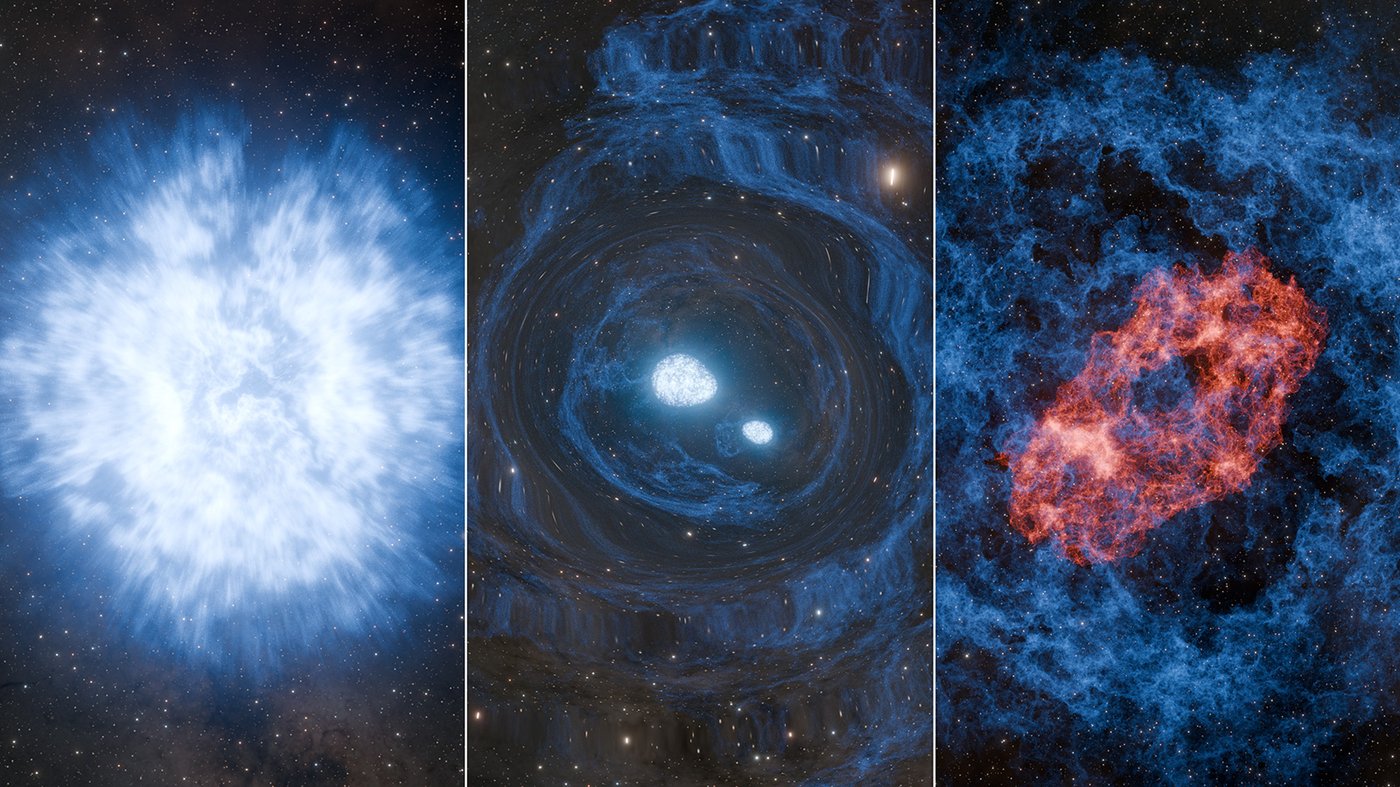

A double explosion, in which a dying star split, then recombined, may be a long-hypothesized but never-before-seen "superkilonova."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists may have witnessed a massive, dying star split in two and then crash back together, triggering a never-before-seen double explosion. The explosion sent ripples through space-time and forged some of the universe's heaviest elements.

Most massive stars reach the ends of their lives by collapsing and exploding as supernovas, seeding the cosmos with elements such as carbon and iron. A different kind of cataclysm, known as a kilonova, occurs when the ultradense remnants of dead stars, called neutron stars, collide, forging even heavier elements like gold.

The newly identified event, named AT2025ulz, appears to combine these two types of cosmic explosions in a way that scientists have long hypothesized but never before observed.

Article continues belowIf confirmed, it could represent the first example of a "superkilonova," a rare hybrid blast in which a single object produces two distinct but equally dramatic explosions.

"We do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova, but the event nevertheless is eye opening," study lead author Mansi Kasliwal, a professor of astronomy at Caltech, said in a statement.

The findings are detailed in a study published Dec. 15 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A two-in-one combo

AT2025ulz first caught astronomers' attention on Aug. 18, 2025, when gravitational wave detectors operated by the U.S.-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and its European partner, Virgo, registered a subtle signal consistent with the merger of two compact objects.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Soon after, the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory in California spotted a rapidly fading red point of light in the same region of the sky, according to the statement. The event's behavior closely resembled that of GW170817 — the only confirmed kilonova, which was observed in 2017 — with its red glow consistent with freshly forged heavy elements such as gold and platinum.

Instead of fading as astronomers typically expect, AT2025ulz began to brighten again, the study reported. Follow-up observations from a dozen observatories around the world, including Hawaii's Keck Observatory, showed the light shifting toward bluer wavelengths and revealing fingerprints of hydrogen, a hallmark of a supernova rather than a kilonova.

That data helped researchers confirm the presence of hydrogen and helium, indicating that the massive star had shed most of its hydrogen-rich outer layers before detonating, the paper noted.

To explain the baffling sequence, the team proposed that a massive, rapidly spinning star collapsed and exploded as a supernova. But instead of forming a single neutron star, its core split into two smaller neutron stars. Those newborn remnants then spiraled together and collided within hours, triggering a kilonova inside of the expanding debris of the supernova.

The combined effect is a hybrid explosion in which the supernova initially masks the kilonova's signature, accounting for the unusual observations, the researchers wrote in the paper.

Clues from the gravitational-wave data bolster this idea. While the signal cannot precisely determine the individual masses of the two merging neutron stars, it does rule out scenarios in which both were heavier than the sun, the new paper noted.

The researchers find a 99% chance that at least one of the objects was less massive than the sun— an outcome that challenges conventional stellar physics, which predicts neutron stars should not weigh less than about 1.2 solar masses. Such lightweight neutron stars can form only when a very rapidly spinning star collapses, matching the scenario proposed for AT2025ulz, according to the statement.

However, the study noted that the complexity of the overlapping signals makes it difficult to rule out the possibility that the signals came from unrelated events that happened to occur close together. Ultimately, the only way to test the theory will be to find more such events using next-generation sky surveys such as those from Vera C. Rubin Observatory and NASA's upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, the researchers said.

"If superkilonovae are real, we'll eventually see more of them," study co-author Antonella Palmese, an assistant professor of astrophysics and cosmology at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania, said in a different statement. "And if we keep finding associations like this, then maybe this was the first."

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Space.com, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus