Giant 'metal cloud' spotted in nearby star system could be hiding a second alien sun

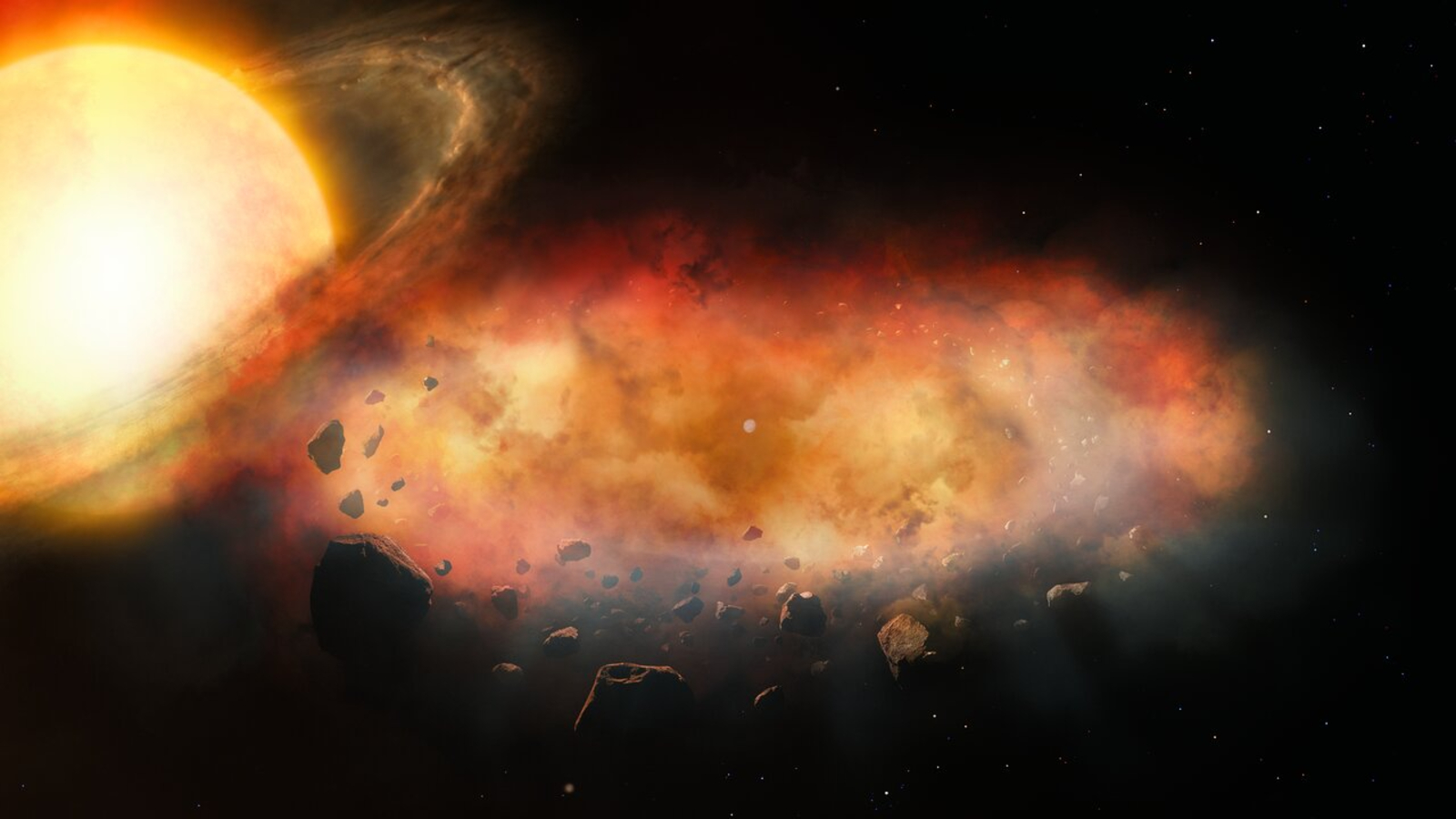

Astronomers suspect that a massive metallic cloud swirling in a nearby star system could be hiding a giant planet or dwarf star from view, after it drastically dimmed a sun-like star for around nine months.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A giant cloud of vaporized metal may be hiding a secret planet or second alien sun in a nearby star system, a new study reveals.

The mysterious cloud is up to 15,000 times wider than our planet, and made its home star almost completely disappear from telescope observations for nearly nine months when the ghostly object oozed between its host star and Earth.

Astronomers were first alerted to the mysterious cloud's presence in September 2024, when they detected a surprise dimming event surrounding the star J0705+0612 (sometimes referred to as ASASSN-24fw) — a sun-like, main sequence star around 3,000 light years from Earth. The star's brightness suddenly fell 40-fold, to around 3% of its original luminosity, and remained that way for just over eight and a half months before returning to full brightness in May 2025.

"Stars like the sun don't just stop shining for no reason," study lead author Nadia Zakamska, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement. "So dramatic dimming events like this are very rare."

In the study, published Jan. 21 in The Astronomical Journal, Zakamska and her team analyzed this strange event using data captured by the Gemini South telescope and the Magellan Telescopes in Chile, and found that a massive object had passed in front of, or occulted, J0705+0612. After ruling out things like giant planets and asteroid belts, which were either too small or too diffuse to block out so much light for so long, the researchers concluded that the occulting object was a thick cloud of molecular gas.

The unnamed cloud is approximately 125 million miles (200 million kilometers) across and is positioned around 13.3 astronomical units (or roughly 13.3 Earth-sun distances) from J0705+0612. For context, that would put it around halfway between Saturn and Uranus if it were located in our solar system. At this distance, it takes about 44 years for the cloud to fully orbit its home star.

Gemini South's newly operational Gemini High-resolution Optical Spectrograph (GHOST) instrument, which captures specific wavelengths of light given off by different molecules, played a key role in the study. It peered deeper into the cloud than other telescopes can, enabling the researchers to probe exactly what the cloud was made of.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results "exceeded all expectations," revealing an abundance of metals, such as iron and calcium, Zakamska said. The GHOST data also enabled the team to track subtle movements within the cloud, which is "something we've never been able to do before in a system like this," she added.

After reviewing the cloud's movements, it quickly became clear that the metallic mass was being held together by a hefty object at its center. Based on the size of the cloud, this could either be a gas giant several times larger than Jupiter, a low-mass star in a binary pair with J0705+0612, or a brown dwarf — a sort of planet-star hybrid that's more massive than Jupiter but not massive enough to sustain nuclear fusion in its core.

If the cloud surrounds a star, then it would be classified as a circumsecondary disk because its host star is the secondary, or smaller, star in its binary pair. But if it is being held together by a planet, then it would be dubbed a circumplanetary disk. The researchers suggest the cloud is more likely held together by a star, due to high levels of infrared radiation glowing from the cloud. However, it is too early to tell for sure.

The next mystery is how the cloud formed. The researchers predict that the cloud is around 2 billion years old, hinting that it is younger than J0705+0612, which is likely closer in age to the sun (around 4.6 billion years old). This would mean that it is not left over from the star system's creation, like most other similar disks.

Instead, the researchers predict that it was birthed by a planetary collision, similar to the one that birthed the moon. This would not only explain the cloud's age but also its surprisingly high metal content, the researchers argue.

"This event shows us that even in mature planetary systems, dramatic, large-scale collisions can still occur," Zakamska said. "It's a vivid reminder that the universe is far from static — it's an ongoing story of creation, destruction, and transformation."

Researchers will likely learn more about this mysterious cloud in 2068, when it will next pass between J0705+0612 and Earth.

Zakamska et al. (2026). ASASSN-24FW: Candidate gas-rich circumsecondary disk occultation of a main-sequence star. The Astronomical Journal, 171(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ae1fd9

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus