James Webb telescope reveals sharpest-ever look at the edge of a black hole — and it could solve a major galactic mystery

The James Webb Space Telescope snapped its sharpest image of the area around a black hole, solving a long-standing galactic mystery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have revealed the James Webb Space Telescope's (JWST) sharpest-ever image of the area around a black hole. The spectacular view could help solve a decades-long mystery while reversing a long-held belief about space's most extreme objects.

Since the 1990s, astronomers have observed a curious brightness in infrared wavelengths surrounding the active supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the centers of some galaxies. Previously, they attributed these excess infrared emissions to the outflows — superheated streams of matter blasted from black holes.

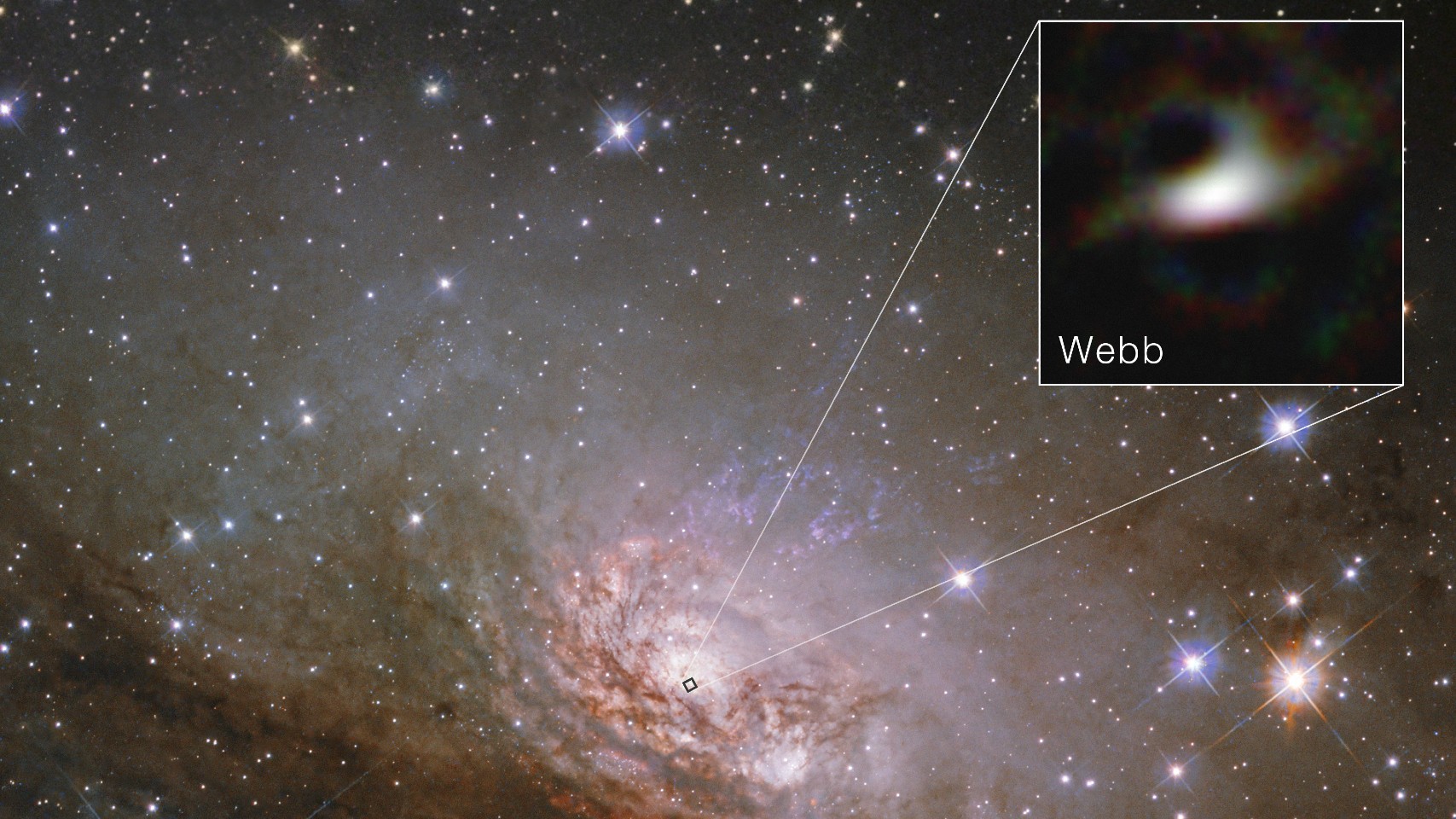

But in a new study published Jan. 13 in the journal Nature Communications, an international team of researchers used JWST to look into the heart of the nearby Circinus galaxy, located only about 13 million light-years from Earth, to reveal the area around the galaxy's SMBH.

The data from JWST, paired with numerous ground-based observations, reveal that the infrared excess is coming from the disk of dusty material that's falling into the Circinus galaxy's central SMBH, rather than from material flowing away from it.

This galactic revelation can help astronomers better understand the growth and evolution of SMBHs, as well as these massive dark monsters' influence on their host galaxies.

Of doughnuts and disks

Active black holes like those at the centers of galaxies are fed by a giant ring of infalling gas and dust. As a black hole draws material from the inner wall of this "doughnut," known as a torus, the material forms a thinner accretion disk that spirals into the black hole like water spiraling into a drain.

The black hole's tidal forces accelerate the infalling matter to great speeds. The resulting friction within the disk causes the swirling matter to emit light that glows so brightly that it obscures astronomers' view of the inner region around the black hole.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Yet black holes are not vacuum cleaners, and even they have a feeding limit. So they blast some of the swirling material back into space, in the form of jets or "winds." Therefore, an understanding of the nature of a black hole's torus, accretion disk and outflows is key to knowing how black holes of various sizes accrete and expel matter to potentially shape their host galaxies by quenching or enhancing star formation across galactic scales.

Resolving a long-standing mystery

The dense gas and bright starlight in Circinus previously prevented astronomers from viewing the galaxy's central region and SMBH in detail.

"In order to study the supermassive black hole, despite being unable to resolve it, they had to obtain the total intensity of the inner region of the galaxy over a large wavelength range and then feed that data into models," lead study author Enrique Lopez-Rodriguez, a galaxy evolution researcher at the University of South Carolina, said in a NASA statement.

Earlier models separately fit the observed spectra of the torus, accretion disk and outflows, but they couldn't resolve the region in its entirety. As a result, astronomers could not explain which part of the SMBH's surroundings caused the excess emissions in infrared light.

JWST's advanced capabilities allowed astronomers to peer through the dust and starlight of Circinus so they could get a sharper view of the SMBH's environment. To do so, they used an imaging technique known as interferometry.

Ground-based interferometry generally requires an array of telescopes or mirrors that work together to gather and combine light from a celestial object over a large area. By combining light from multiple sources, this method causes the electromagnetic waves that form that light to create interference patterns that astronomers can analyze to reveal the sizes, shapes and other characteristics of those objects.

Unlike these terrestrial facilities, however, the space-based JWST can operate as its own interferometer array via its aperture masking interferometer (AMI), a component of the telescope's Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) instrument. Like a camera aperture, AMI is an opaque physical mask with seven small, hexagonal holes that control the amount and direction of light entering JWST's detectors.

Overall, AMI effectively doubles JWST's resolution. "This allows us to see images twice as sharp," Joel Sanchez-Bermudez, an astrophysicist at the National University of Mexico and co-author of the study, said in the statement. "Instead of Webb's 6.5-meter [21 feet] diameter, it's like we are observing this region with a 13-meter space telescope."

By doubling its resolution, JWST captured its sharpest-ever view of a 33-light-year-wide area at the center of Circinus. This unprecedented image allowed researchers to calculate that the majority — around 87% — of the excess infrared emissions come from the dusty disk that's actively feeding the central black hole; "the inner surface of the hole of the doughnut," Lopez-Rodriguez said via email. Whereas previous research had suggested that the excess may have come from hot dusty winds, or even the galaxy’s residual starlight, the team found that less than 1% of these emissions come from the energetic outflows streaming away from the SMBH.

The accretion may be extinguishing star formation in the center of Circinus, but confirming this will require a different type of JWST-based observation, Lopez-Rodriguez said.

An invaluable perspective

In addition to revealing previously hidden SMBH mechanics, this research highlights the potential of JWST-based interferometry for studying various celestial objects, including other active SMBHs at the cores of nearby galaxies. By increasing the sample size, astronomers hope to determine whether the infrared emissions from other SMBHs are due to their dusty disks or to their hot outflows.

"AMI has to be used — in order to get precious JWST time — on targets which cannot be done from the ground, or at wavelengths that are blocked by the Earth's atmosphere," study co-author Julien Girard, a senior research scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, told Live Science via email.

AMI-based observations can better illuminate our own solar system; they recently offered a detailed look at the volcanoes on Jupiter's hellish moon Io, Girard added. So AMI can observe diverse cosmic objects of varying shapes and sizes, from moons oozing with lava to black holes obscured by dust. In the future, it could help astronomers detect moons around prominent asteroids or reveal the orbits and masses of multistar systems, Girard added.

Ivan is a long-time writer who loves learning about technology, history, culture, and just about every major “ology” from “anthro” to “zoo.” Ivan also dabbles in internet comedy, marketing materials, and industry insight articles. An exercise science major, when Ivan isn’t staring at a book or screen he’s probably out in nature or lifting progressively heftier things off the ground. Ivan was born in sunny Romania and now resides in even-sunnier California.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus