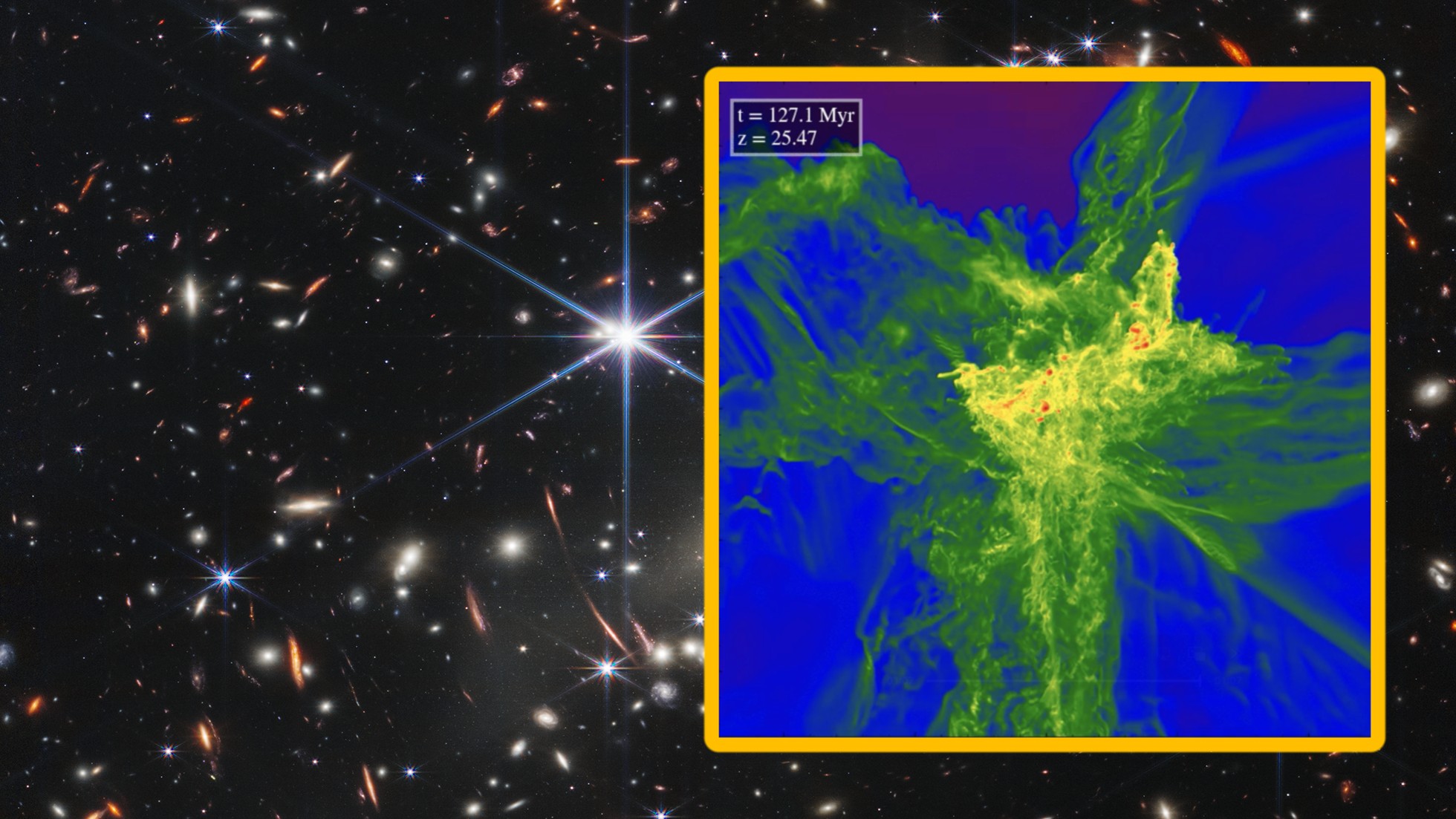

James Webb telescope spots 'monster stars' leaking nitrogen in the early universe — and they could help solve a major mystery

Researchers using the James Webb Space Telescope spotted huge stars leaking nitrogen in an early galaxy, hinting that such 'monster stars' might have been the source of ancient supermassive black holes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have spotted the first evidence of "monster stars" in the early universe — offering new clues to how supermassive black holes grew so big after only a billion years of the universe's history.

The team spotted these gargantuan stars — each with a mass of between 1,000 and 10,000 times our sun — in a galaxy called GS 3073, which formed roughly about a billion years after the Big Bang. It is believed that monster stars like these led to the formation of these early supermassive black holes.

The study was co-led by scientists from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the University of Portsmouth in the U.K., and was published Nov. 12 in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"Our latest discovery helps solve a 20-year cosmic mystery," study co-author Daniel Whalen, from Portsmouth's Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, said in a statement. "These cosmic giants would have burned brilliantly for a brief time, before collapsing into massive black holes, leaving behind the chemical signatures we can detect billions of years later."

"A bit like dinosaurs on Earth, they were enormous and primitive," Whalen added. "And they had short lives, living for just a quarter of a million years, a cosmic blink of an eye."

The research's implications include learning about the first generation of stars, as well as literally shedding light on the "cosmic dark ages", or the period of time when the first stars came to light and the chemistry of the universe began to change.

A peculiar signature

The stars in GS 3073 had an unusual and "extreme" imbalance of nitrogen to oxygen (a ratio of 0.46) not usually found in stars or stellar explosions, according to the team. The signature, however, matched something predicted in models: "primordial stars thousands of times more massive than our sun," study co-author Devesh Nandal, a postdoctoral fellow at the CfA's Institute for Theory and Computation, said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

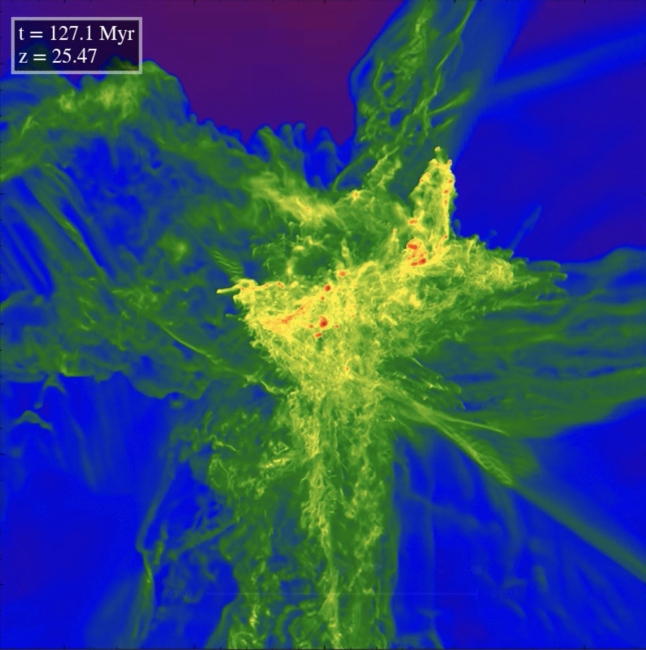

How did these stars produce so much nitrogen? The researchers said it's a three-step process. Stars are constantly burning elements in their cores. As these large stars in GS 3073 burned helium, the chemical reactions created carbon. Eventually, carbon began to invade an outside shell of material, where hydrogen was burning. In that outside shell, the carbon and hydrogen then mixed to create nitrogen.

As the nitrogen was produced, convection currents within the star began to distribute it throughout the star's body. Over time, the nitrogen left the star and flowed into space. In the case of GS 3073, this process lasted millions of years.

"The study also found that this nitrogen signature only appears in a specific mass range," the researchers noted. "Stars smaller than 1,000 solar masses, or larger than 10,000 solar masses, don't produce the right chemical pattern for the signature, suggesting a 'sweet spot' for this type of enrichment."

The big black hole mystery

Based on their models, the researchers further suggested that when these monster stars reach the end of their lives, they don't explode into supernovas. What happens next is instead a big collapse, generating some of the universe's earliest supermassive black holes.

Adding more fuel to this idea: GS 3073 does appear to have an actively feeding black hole at its center, "potentially the very remnant of one of these supermassive first stars," the statement noted. "If confirmed, this would solve two mysteries at once: where the nitrogen came from and how the black hole formed."

The origin of the universe's first supermassive black holes remains one of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics. Some theories suggest they collapsed directly from ultra-dense clouds of gas shortly after the Big Bang and then formed galaxies around them; other theories point to more exotic explanations, such as dark matter interactions or the collapse of monster stars. Ultimately, more research is needed to solve this ancient puzzle.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus