Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

People with anxiety or insomnia tend to have weaker immunity. The decline of a key immune cell may be a culprit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Stress, anxiety and sleepless nights do more than erode peace of mind — they can also weaken the body's defenses, making people more susceptible to infections, cancers and autoimmune disorders. Now, scientists have uncovered a potential mechanism that may link these psychological factors and immunity issues.

In a new study, published Dec. 10 in the journal Frontiers in Immunology, researchers zeroed in on a type of immune cell called natural killer (NK) cells that may play a key role.

The research was partly inspired by a 2022 national screening study conducted in Saudi Arabia that showed generalized anxiety order (GAD) was on the rise, and that the trend was most pronounced in women. People with GAD experience constant, uncontrollable worrying, and their concern is typically more intense than the situation calls for; this can cause an array of related symptoms, including sleep problems.

Article continues belowThis finding led immunologist and lead study author Renad Alhamawi at Taibah University in Medina, Saudi Arabia, to explore how anxiety might affect immunity among women.

Alhamawi and her colleagues recruited 60 female students between ages 17 and 23 and asked them to fill out a questionnaire about their mental health. The responses showed that 75% reported symptoms consistent with GAD — such as feeling nervous, being so restless that it's hard to sit still, or becoming easily irritable— including 13% with severe symptoms. (Although the participants were screened for GAD symptoms, none were officially diagnosed as part of this study.)

About 53% of the cohort, or 32 students, reported not getting enough sleep.

Next, the researchers took blood samples from the participants and surveyed the levels of various immune cells, which revealed that those who experienced anxiety-like symptoms had 38% fewer NK cells than those without symptoms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

NK cells are one of the first types of immune cells to respond to an infection or to the presence of cancer in the body, and immunologists split them into two subsets. The first subset secretes enzymes that break down and "kill" diseased cells. The second subset works by secreting protein signals, called cytokines, that regulate other immune cells. A reduced abundance of these dual-action cells could potentially predispose individuals to disease.

The participants who reported anxiety symptoms had reduced levels of both subsets of NK cells, while people reporting insufficient sleep had 40% fewer of the immune-regulating subset of cells only.

Importantly, this study found only a correlation between these anxiety symptoms, sleep and reduced NK cell levels; the researchers have yet to explore a causal link, let alone investigate whether this drop in NK cells could lead to markedly higher rates of disease.

It is not yet clear what factors might be behind this change in NK cell abundance in the bloodstream. For example, it could be that the cells die off or that the body renews them at a slower rate.

Also, "focusing on circulating NK cells [in the blood] does not allow investigation of NK cells infiltrating the nervous system," Stefano Garofalo, an immunologist at the Sapienza University of Rome who was not involved with the work, told Live Science in an email. He speculated that the drop in NK cells could happen if they migrate from the bloodstream into nerve tissue in people who have anxiety or insomnia. His research focuses on how NK cells help regulate brain function and shape behavior in mice.

These findings are consistent with those from other research, such as a study on chronic tinnitus, wherein participants who reported higher stress levels had fewer cell-killing NK cells. Alhamawi said that the stress hormone cortisol may drive down NK cell populations because it is known to exert other immune-suppressing effects. For instance, cortisol can hinder antigen-specific T cells, a type of immune cell that recognizes features of specific threats, like viruses.

"Anxiety increases the level of cortisol, so we think it might affect the number of NK cells in an indirect way," Alhamawi said.

The current research has a few caveats. "The main limitation of the study is the very small participant group, consisting exclusively of women under 25 years of age and belonging to a single ethnic background," Garofalo said. Future studies could determine if the correlation is more generalizable, using a larger mixed-sex population of individuals from different backgrounds.

Alhamawi noted that she would like to perform a long-term study, in which researchers track how anxiety, sleeping patterns and NK cell levels change over time in the same cohort of participants. That could provide a clearer picture of the relationship between these psychological factors and immunity, as well as the incidence of disease.

"We can see if there is [an] effect by testing if they develop more infectious disease or chronic disease," she added.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

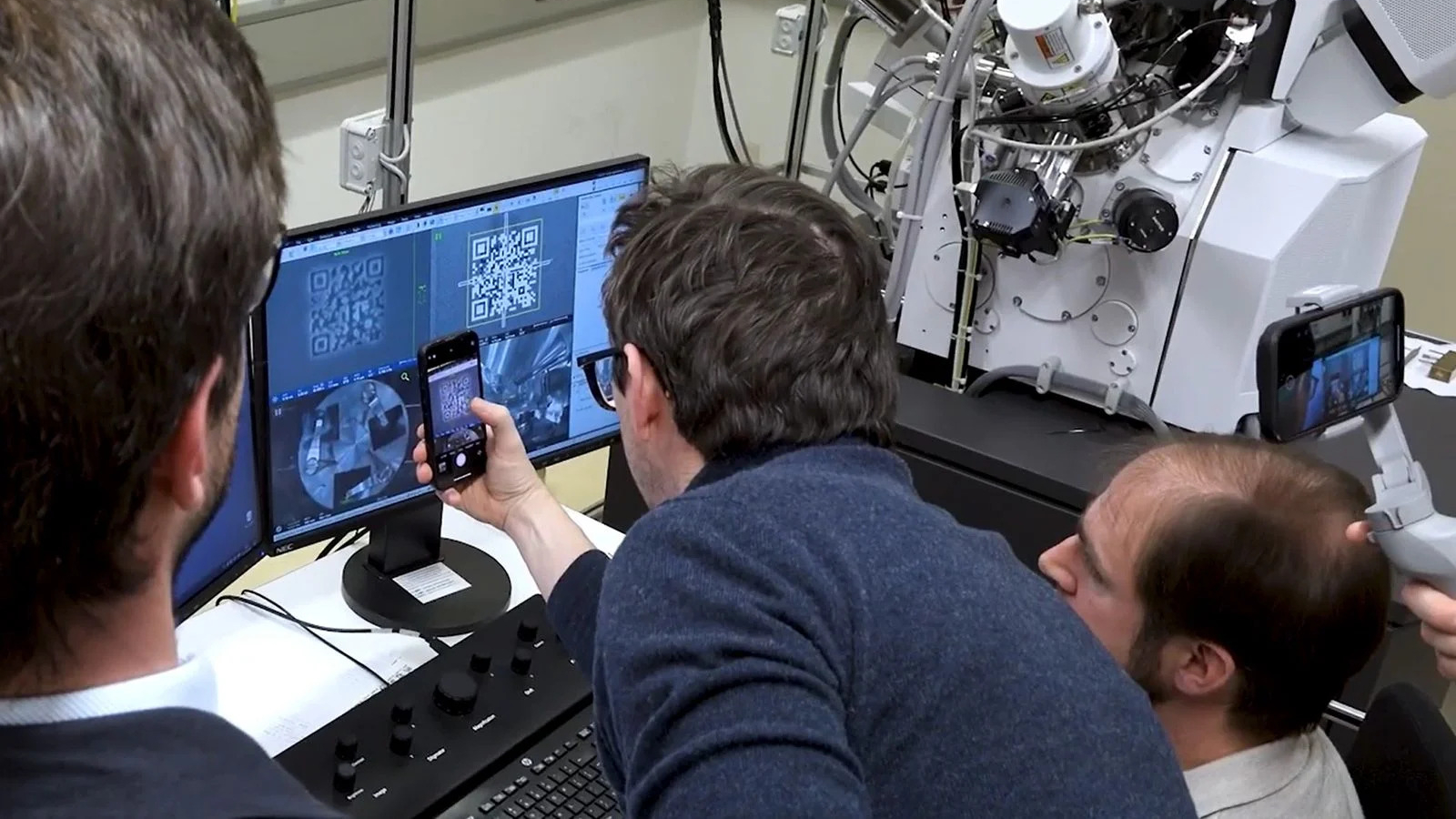

Kamal Nahas is a freelance contributor based in Oxford, U.K. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science and The Scientist, among other outlets, and he mainly covers research on evolution, health and technology. He holds a PhD in pathology from the University of Cambridge and a master's degree in immunology from the University of Oxford. He currently works as a microscopist at the Diamond Light Source, the U.K.'s synchrotron. When he's not writing, you can find him hunting for fossils on the Jurassic Coast.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus