Master regulator of inflammation found — and it's in the brain stem

Research in mice suggests that specific neurons within the brain stem act like the dial on a thermostat — fine-tuning inflammation as and when required.

Scientists have found a master regulator of inflammation — and it's in the brain stem.

New research in mice has revealed that the neurons in the brain stem act like a thermostat, ramping up or down inflammation in response to signals sent by the vagus nerve, which connects the brain to other organs in the body.

In the early stages of an infection, these neurons might encourage a helpful, proinflammatory response to thwart invading pathogens. However, once an infection is cleared, the neurons tamp down this response to prevent unwanted damage to healthy cells. Researchers described this feedback system in a new study published May 1 in the journal Nature.

If a similar feedback loop is found in humans, scientists could one day identify drugs that regulate it. For instance, drugs that target this brain stem thermostat could be used to reduce inflammation in diseases where it goes out of whack, such as autoimmune diseases, the researchers said.

"If we can come up with small molecules that go into these neurons and turn them on, now you may have a way of regulating the circuit and therefore changing the way they are modulating body immunity and the inflammatory state," Charles Zuker, head of the laboratory where the study was carried out and a professor of biochemistry, molecular biophysics and neuroscience at Columbia University, told Live Science.

The brain stem connects the main part of the brain, the cerebrum, to the cerebellum and the spinal cord, and it regulates key involuntary functions such as breathing and heart rate. Researchers already knew that the brain and the immune system communicate closely with one another, but the role of the brain stem in that process wasn't clear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists also knew that the vagus nerve plays a key role in inflammation; stimulating the nerve has been shown to work in several inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and rheumatoid arthritis. However, exactly how all these players interact wasn't clear.

To elucidate that relationship, in the new study, Zuker and colleagues stimulated an infection in mice using bacterial molecules that normally trigger an inflammatory response.

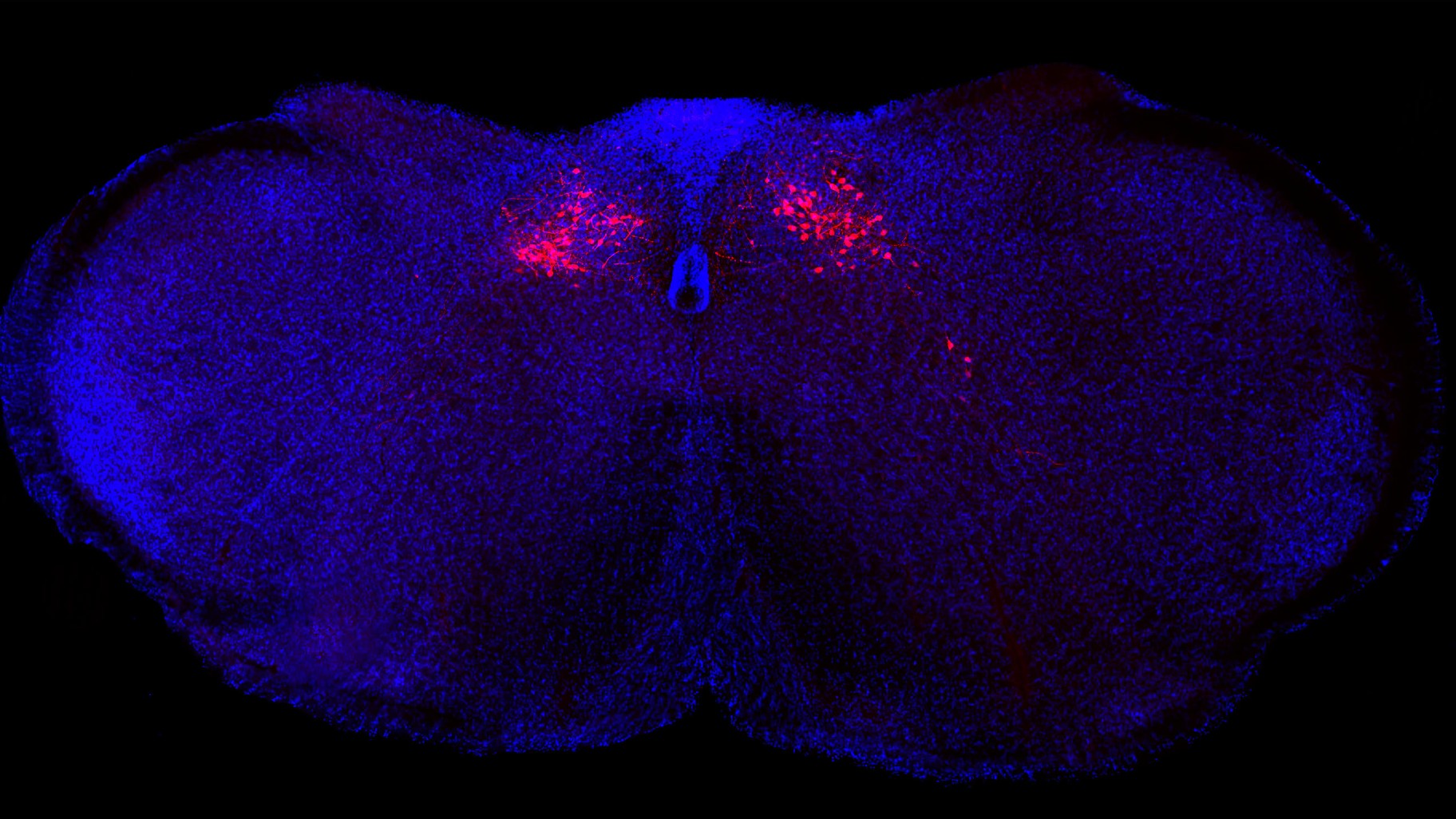

The molecules triggered the vagus nerve to send signals to neurons in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (cNST) in the brain stem.

In a separate experiment, quieting these cNST neurons triggered a heightened inflammatory response, causing the body to crank out three times more pro-inflammatory molecules and three times less anti-inflammatory molecules than is typical in healthy mice.

Stimulating these neurons, meanwhile, had the opposite effect — levels of pro-inflammatory molecules declined by nearly 70% while anti-inflammatory molecules soared by almost 10-fold. This suggests that cNST neurons may control the body's inflammatory response to infection, the team said.

Despite these promising initial findings, many questions remain. For instance, more research will be needed to understand the nature of the signals that pass from the brain stem to immune cells in the rest of the body, Tamar Ben Shaanan, a postdoctoral scholar in microbiology and immunology at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email.

It would also be important to decipher how the complex immune "picture" is being seen in the brain, said Jonathan Kipnis, a professor of pathology and immunology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who was also not involved in the research.

For example, future research could investigate whether the brain knows that an infection has taken place, can identify which exact infection it is or develop memory of it in case of subsequent reinfection, he told Live Science in an email.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus