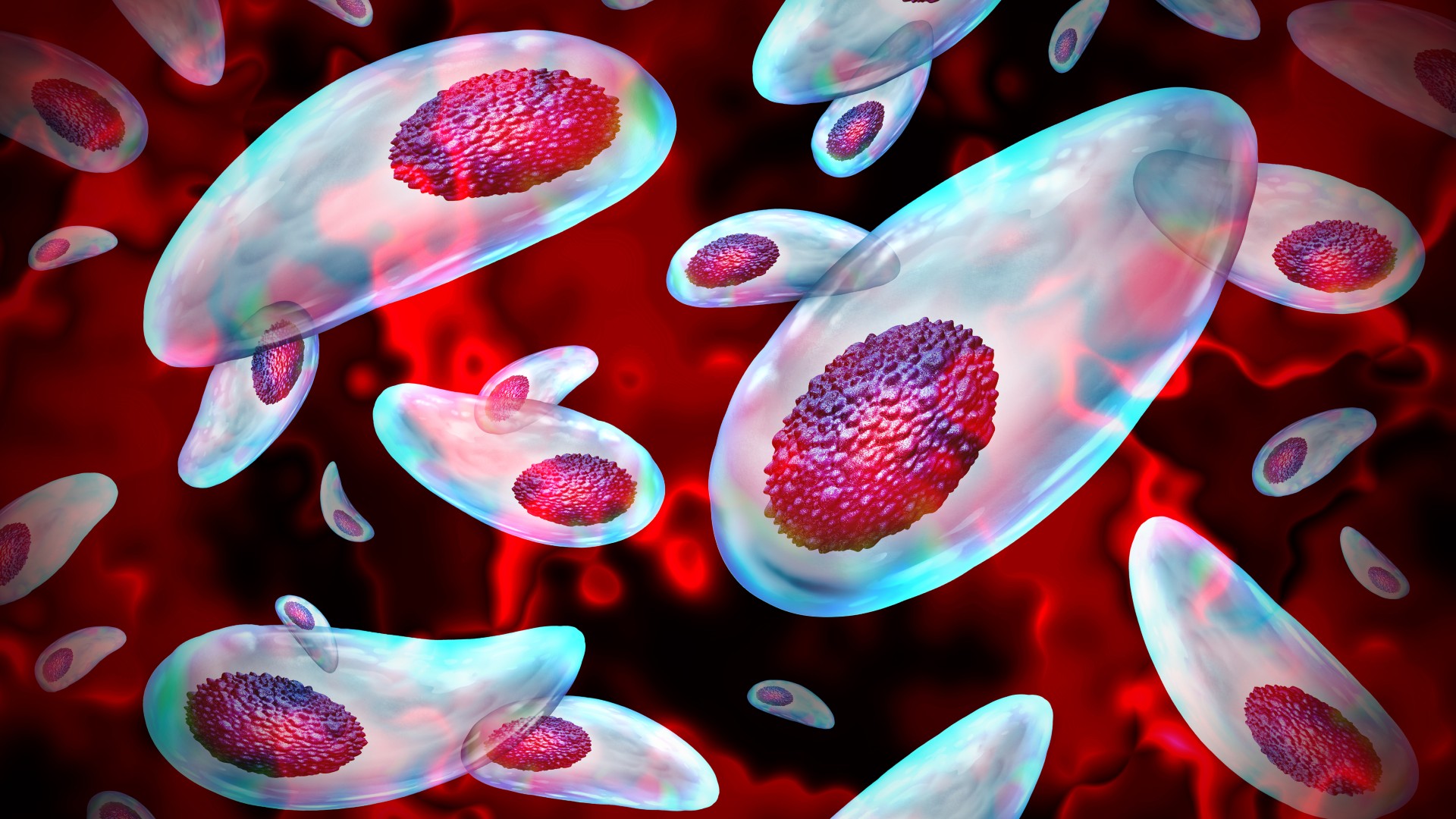

Infection with cat parasite Toxoplasma may drive 'inflammation aging' in older adults

A small study of older adults in Iberia suggests that infection with the common parasite Toxoplasma may be linked to 'inflammaging' and frailty in older adults.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Older people who have had chronic infection with the "cat parasite" Toxoplasma gondii may have a higher risk of inflammation and frailty, a small study suggests.

In an analysis of more than 600 people over age 65, scientists found that almost 70% had been infected with T. gondii — a single-celled parasite that normally lives in cats but can infect humans.

The more parasite-attacking antibodies people had in their blood, the more likely they were to show signs of frailty, such as losing weight unintentionally or being physically weaker. They also tended to have higher levels of blood chemicals tied to frailty and inflammation as we age.

"Our study described for the first time, the intersection between the parasite Toxoplasma gondii and frailty," study co-senior author Blanca Laffon Lage, a psychobiologist at the Universidade da Coruña in Spain, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 10 surprising facts about the 'mind-control' parasite Toxoplasma gondii

"The results showed that, among older adults infected with the parasite, those with higher 'serointensity' (higher concentration of antibodies to the parasite) were significantly more likely to be frail," she said.

However, the study, published Nov. 6 in The Journals of Gerontology, Series A, did not have a control group. Therefore, the authors can't conclude whether T. gondii infection causes frailty or whether other risk factors for frailty, such as depression, contribute to T. gondii infection by making people more likely to neglect themselves or their food prep hygiene, the authors wrote in the paper.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nevertheless, these initial findings may encourage more studies on other "unexplored targets" that may "exacerbate frailty" Laffon Lage said.

As we age, our bodies are exposed to persistent, low levels of inflammation in the absence of infection, known as "inflammaging," which can contribute to frailty in later life and be exacerbated by chronic infections.

Infection with T. gondii triggers the immune system to produce antibodies to fight off the infection, called toxoplasmosis. Most people, except those who have weakened immune systems or are pregnant, can easily control toxoplasmosis and subsequently don't develop any symptoms. In fact, more than 40 million adults in the U.S. are estimated to be infected with T. gondii, though the vast majority don't know it. However, the parasite often remains in the body — for example, as slow-growing cysts in muscle and brain tissues that trigger low levels of chronic immune activation and the upregulation of pro-inflammatory molecules called cytokines.

With this in mind, the study authors hypothesized that chronic T. gondii infection may be associated with inflammaging and frailty in older adults. They took blood samples from 601 people in Spain and Portugal, 403 of whom had T. gondii antibodies, meaning they'd previously been infected with the parasite. They also measured the people's frailty using a five-point scale and considered other potential influential factors, such as having depression or being cognitively impaired.

Even after considering these possible confounders, the authors found that people who had a stronger antibody response to previous T. gondii infection were more likely to be frail. Two types of immune-mediated biomarkers that had previously been linked to frailty — kynurenine/tryptophan and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor II — were also more common in their blood.

If the findings are validated in future studies, they could be used to develop new "preventative and treatment approaches" for frailty that target specific inflammatory biomarkers, the authors wrote in the paper. Further work could also investigate whether dampening the immune response to T. gondii infection could prevent frailty, Laffon Lage said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus