'Universal' cancer vaccine heading to human trials could be useful for 'all forms of cancer'

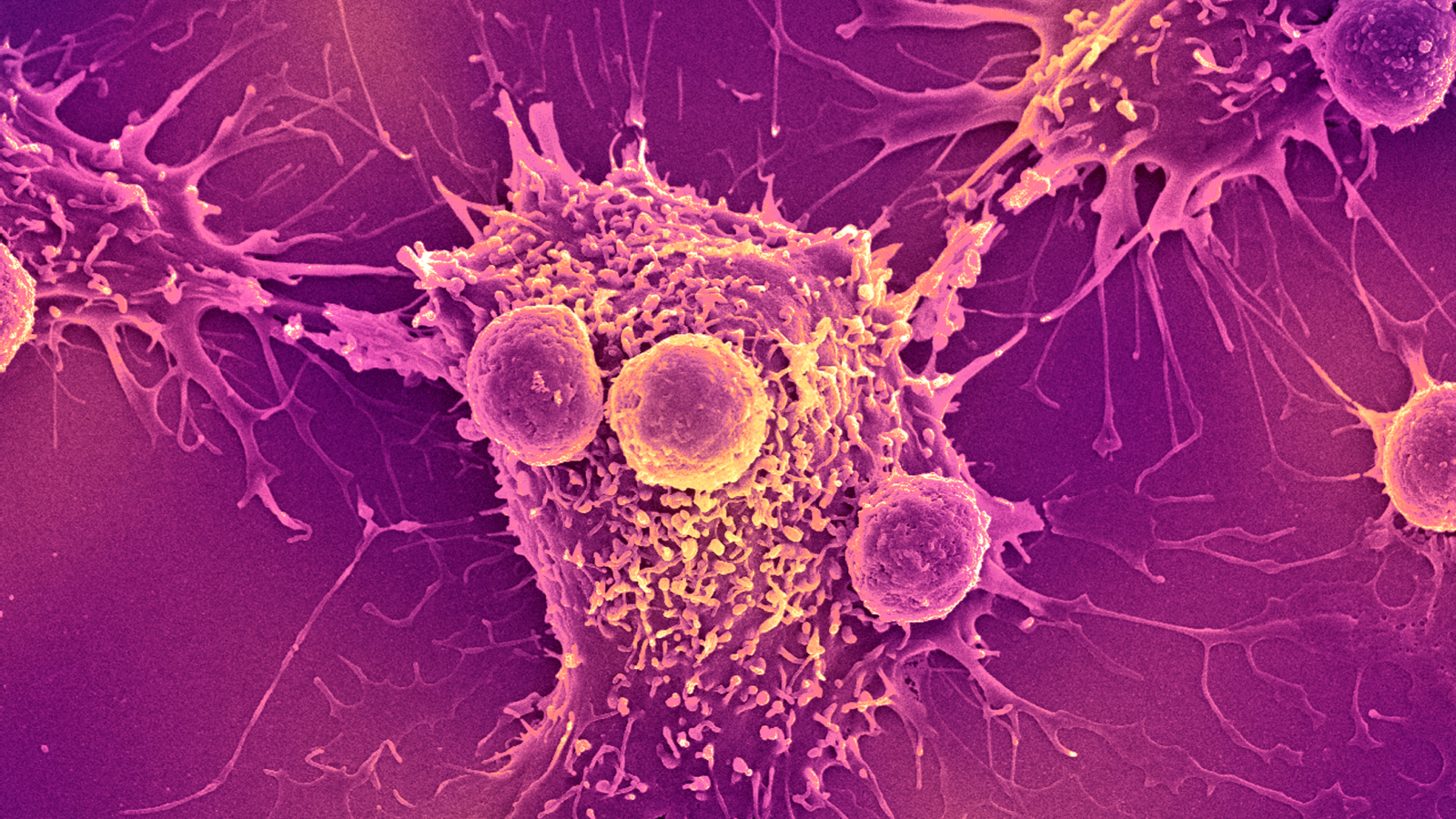

A new mRNA-based vaccine triggers a response from the innate immune system to help arm the body against cancer, a mouse study finds. It's now in early human trials.

A universal cancer vaccine in development could help rev up the immune system against tumors and supercharge the effects of existing cancer therapies, an animal study suggests.

Similar to vaccines for viral infections like the flu, many cancer vaccines are designed to help the immune system recognize specific proteins. However, while conventional vaccines aim to prevent disease, cancer vaccines are currently being developed to clear away cancers already growing in the body and to help prevent treated cancers from coming back.

Nonetheless, conventional vaccines and cancer vaccines often work similarly. The flu shot trains the immune system to look for unique proteins found on the surface of influenza viruses, while cancer vaccines typically teach immune cells to spot unique features of cancer cells.

But there's a challenge: These cancer proteins of interest can often be unique to individual patients, meaning each cancer vaccine may need to be specially formulated for each patient. Although it's possible to craft such personalized vaccines, they take time to make — and, in the interim, the patient's cancer mutates, potentially causing the vaccine to be less effective.

"It can be months from the time you get a patient's specimen to when they actually have a personalized therapy," said study senior author Dr. Elias Sayour, a pediatric oncologist at University of Florida Health. Sayour and colleagues wondered if they could design a cancer vaccine that would not require this personalization and instead ignite a general immune response to keep cancer at bay.

"The idea that something could be available immediately, albeit in a nonspecific way … could be revolutionary for how we bridge therapy and how we manage patients," Sayour told Live Science.

Related: New mRNA vaccine for deadly brain cancer triggers a strong immune response

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An "off-the-shelf" cancer vaccine

The experimental vaccine, described in a report published July 18 in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering, is built upon messenger RNA (mRNA), which also formed the basis of the first COVID-19 vaccines that continue to be updated now.

mRNA acts as blueprints that cells then base new proteins on. In the COVID-19 vaccines, the molecule contains instructions for a bit of the coronavirus; in the new cancer vaccine, it carries instructions for a substance that raises the body's first-line immune defenses, poking the "innate" immune system rather than the "adaptive.".

In particular, the vaccine aims to boost the body's production of type-I interferons — immune messengers that play important roles in controlling inflammation and spotting cancerous tumors in order to eliminate them. In a series of experiments in lab mice, the researchers demonstrated that this signaling is key to snuffing out tumors early in their development. The signals help rally the immune system to attack the tumors and hinder the cancer's growth, and if you block them, tumor growth goes haywire.

Additionally, these experiments showed that this early interferon activity is vital to a common form of cancer treatment, called immune checkpoint inhibitors. These treatments rip the breaks off of immune cells so they maintain a high level of activity and kill off cancer efficiently.

Cancer has ways of hijacking interferon signals and thus thwarting the anti-cancer immune response that follows — so the cancer vaccine acts as a kind of immune "reset," Sayour explained.

The researchers used the vaccine in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor in a mouse model of melanoma, a type of skin cancer. In mice with treatment-resistant tumors, the combo of treatments worked better than checkpoint inhibitors alone, the team found. They also tested the vaccine on its own in mouse models of other cancers, including glioma (a brain cancer) and pulmonary osteosarcoma (bone cancer that's spread to the lungs). It showed promising anti-cancer effects when applied by itself, as well.

For this early work, the team tested a few different mRNA formulations to stir up the interferon response and found that each did so effectively. More work is needed to understand if the mRNA molecules themselves or the proteins they're used to make are more important for triggering this generalized response, Sayour noted.

The current study focused on solid tumors, which tend to be more resistant to immunotherapy than blood cancers are, Sayour said. But "I personally think this can be used for all forms of cancer," he added. "I believe this is a universal paradigm that can be used to treat cancer." In particular, he could see it being applied as secondary prevention, to help stop treated cancers from coming back.

"This exciting and novel paper shows promising evidence that giving the immune system a short, targeted boost at just the right time can help previously unresponsive tumors respond to immunotherapy," said Diana Azzam, an associate professor and scientific director at the Center for Advancing Personalized Cancer Treatments at Florida International University.

"This approach could be especially helpful for 'cold' tumors — types of cancer that usually don't trigger a strong immune response, like pancreatic, ovarian, and some types of breast cancer," Azzam, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. These tumors hide from the immune system and can be difficult to target with immunotherapy, so it's possible that this type of vaccine could help expose these cancers to attack.

"While more research is needed to confirm how well this approach will work in people, the encouraging results in mice offer a strong foundation," Azzam said. In people, you'd want to ensure that the vaccine mounts a helpful immune response without sparking unwanted inflammation in the long run, for instance. "Future studies will address key questions around safety, consistency, and long-term effectiveness in real-world cancer patients," she concluded.

Meanwhile, Sayour and his colleagues have launched a human trial testing a two-hit approach: an off-the-shelf cancer vaccine followed by a personalized one. They're working with patients with two types of recurrent cancers: either pediatric high-grade glioma or osteosarcoma.

"This approach saves valuable time needed for personalized vaccinations and may induce rapid immunity that can be further seized upon by personalized therapy," Sayour said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus