Weird swelling of man's fingers and toes revealed cancer had 'completely replaced' the bones with lesions

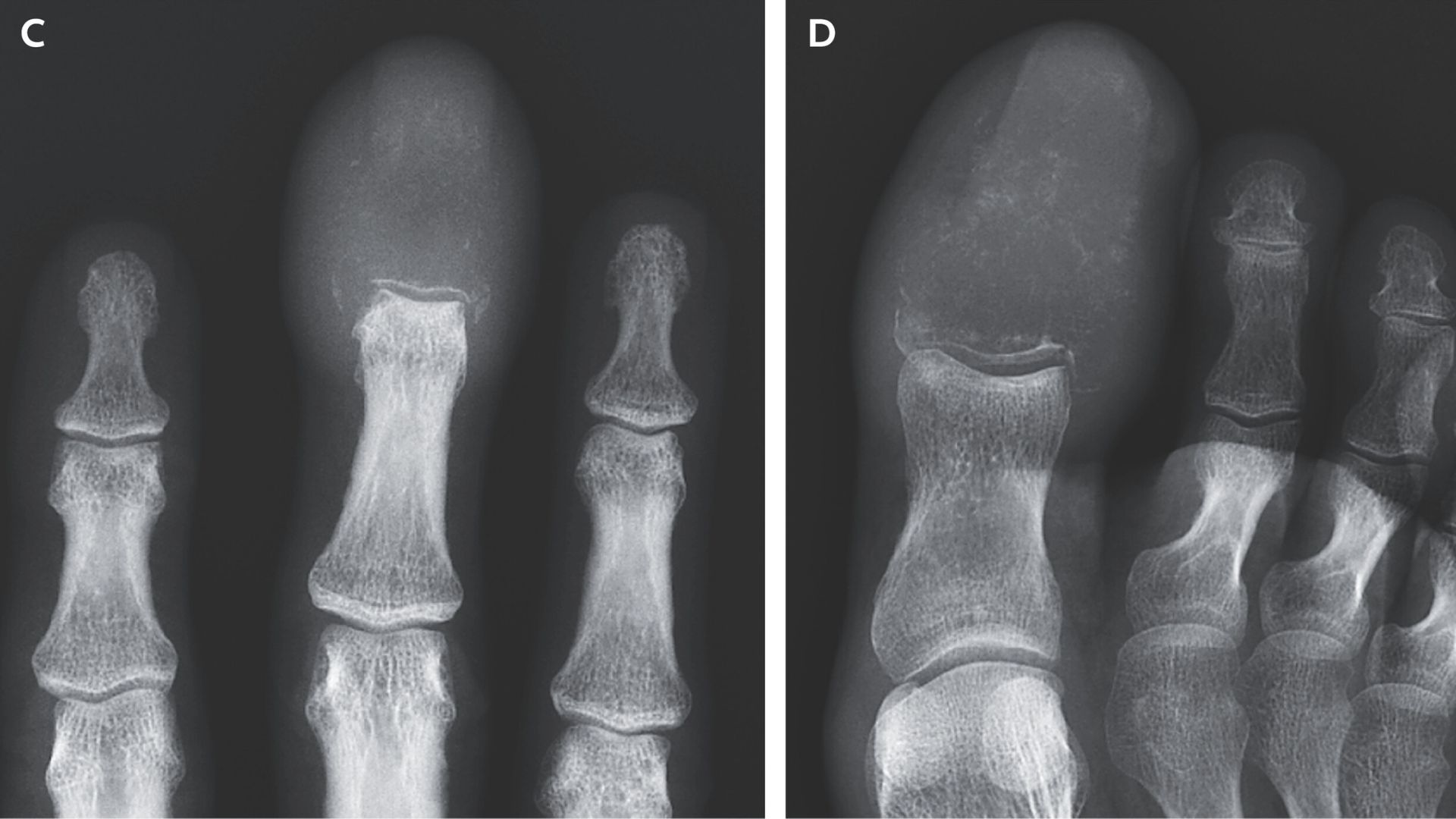

Marked swelling in a man's finger and big toe was a symptom of late-stage cancer.

A man developed painful swelling in his right middle finger and right big toe over the course of six weeks, causing the digits to take on a club-like shape. It turned out that the strange swelling was a rare sign of cancer that had spread through his body.

Prior to developing the swelling, the 55-year-old had been diagnosed with metastatic squamous-cell lung cancer, according to a report of the case published July 16 in The New England Journal of Medicine. This type of cancer starts in the flat, thin cells that line the airways, and in this case, the cancer had reached an advanced stage and spread, or metastasized, to other parts of the body.

After noting the swelling in his finger and toe, the man reported to the hospital for examination. Doctors found that the tip of each affected digit was red and swollen. They also noted that an ulcer was forming near the nail of the affected toe. The swollen areas were firm to the touch and tender, the doctors reported.

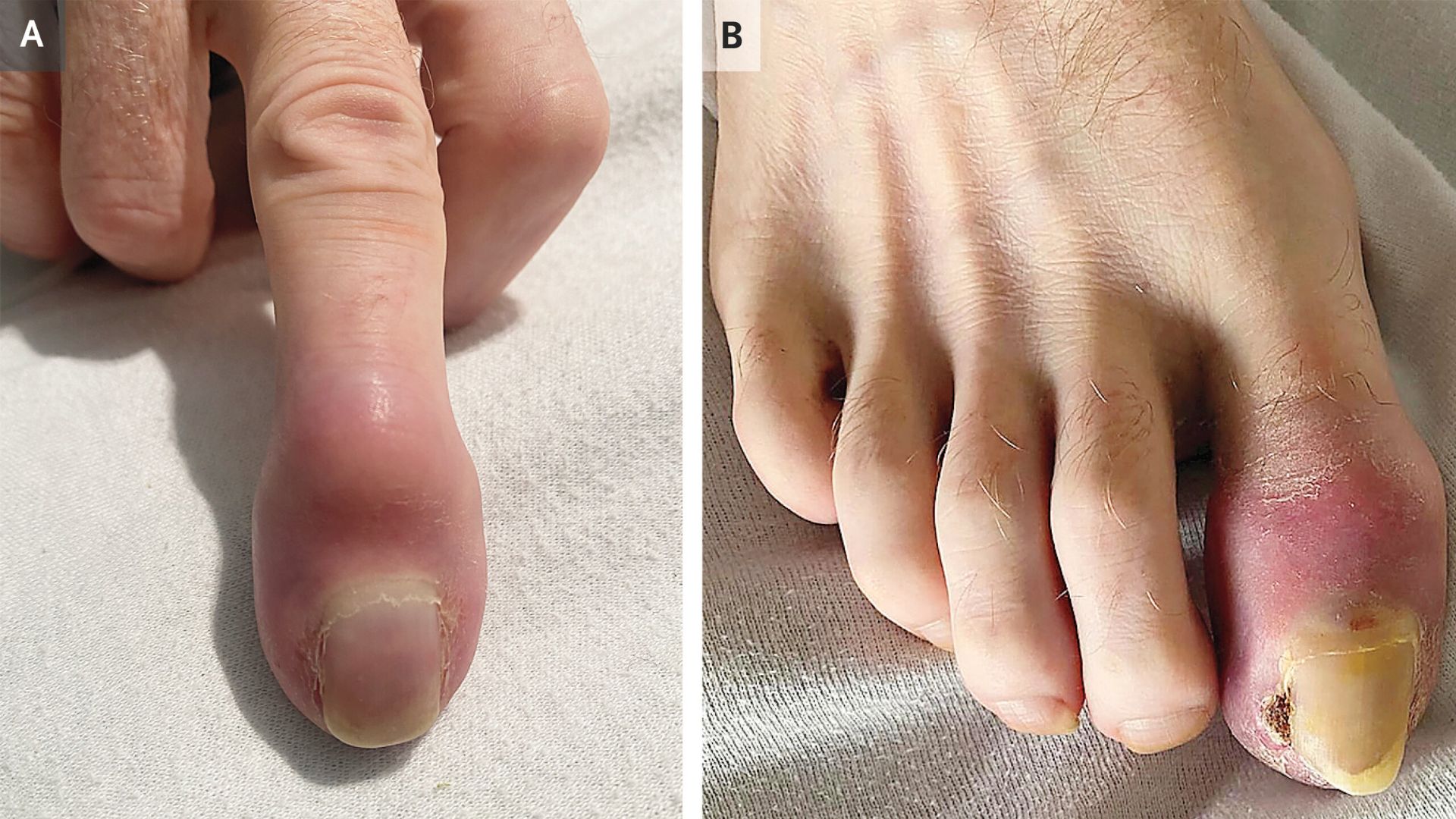

Scans of the man's affected hand and foot revealed "destructive lytic lesions that had completely replaced" the bones in the tips of the middle finger and big toe. Lytic lesions are areas where bone has been destroyed, leaving holes or blank spaces in the skeleton. Such lesions are typically driven by a disease process like cancer.

Cancer that has spread to finger or toe bones may mimic gout or osteomyelitis on a physical examination, but scans called radiographs can help to diagnose the condition, the patient's doctors noted. Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis and osteomyelitis causes inflammation in bones, often due to infection, so both conditions can cause visible redness and swelling.

Based on his radiographs, the man was diagnosed with acrometastasis, a relatively rare form of cancer spread that occurs below the elbow or knee. Acrometastases account for only about 0.1% of cases in which cancer has spread to the bones, according to a 2021 review.

Related: New blood test detects cancers 3 years before typical diagnosis, study hints

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most often, this rare symptom is seen in patients who are already known to have cancer, as in the recent case. But sometimes, the symptoms of acrometastasis are the first sign of a previously undiagnosed cancer. It is most often associated with cancers of the lung, gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary tract, according to the review.

Acrometastases are seen much more often in males than in females, according to the review, which looked at about 250 cases of the conditions that had been published between 1986 and 2020. This sex difference has also been flagged in other reviews of the literature. The bones of the fingers and toes were more likely to be affected than the other bones in the hand and foot, the literature suggests.

Acrometastases are fairly rare because, when cancer spreads to bone, it's usually drawn to the bone marrow, which in adults is found primarily in the long bones of the arms and legs, ribs, backbone, breastbone and pelvis. By comparison, finger and toe bones contain much less marrow. They also receive less blood flow than bones located closer to the heart, so that also may help to explain why cancer spreads to the fingers and toes less frequently, the review suggests.

Because acrometastases are usually seen in late-stage cancer, they're associated with poor survival time — often less than six months from diagnosis of the condition. As such, treatments are typically focused on relieving the patient's pain and retaining as much functionality of the hand or foot as possible. In the 55-year-old's case, doctors started palliative radiotherapy, which aims to relieve a person's symptoms rather than cure their disease.

The doctors reported that the patient died three weeks later from complications of refractory hypercalcemia — dangerously high calcium levels in the blood that do not fall in response to standard treatments. This condition is often, but not always, tied to cancer.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus