2-in-1 COVID-flu vaccine looks promising in trial — but experts say approval may be delayed

Late-stage trial data suggest that a new COVID-flu vaccine offers good protection against both infections, but experts expect the shot's approval may be delayed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two might be better than one: A new vaccine that targets the viruses behind seasonal flu and COVID-19 triggers a stronger immune response than flu and COVID shots given separately, trial data suggest.

The combination shot, dubbed mRNA-1083, is made by the pharmaceutical company Moderna. The promising results of the Phase 3 clinical trial of the vaccine were published May 7 in the journal JAMA. This late-stage trial included two groups of adults ages 50 and older who were given either the new vaccine or a combination of previously approved flu and COVID-19 vaccines.

The trial runners looked at the quantity of antibodies, or protective immune proteins, made in response to each vaccine regimen. Antibody levels correlate with how well a shot should protect against a disease and how long that protection might last. They do not provide direct data on how well a shot drives down infection rates in real life — but ethically, such real-world data is difficult to gather when effective vaccines against an illness already exist.

While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet given mRNA-1083 a final stamp of approval, experts told Live Science that the trial results are largely positive. However, political factors could hinder the shot's approval, some say.

Why do we need a combination vaccine?

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) already recommends that people get both their annual flu and updated COVID-19 vaccines at the same time. But at the moment, that requires two separate shots to be given at the same appointment.

The combination vaccine would be "a one-stop shop," said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious-disease doctor at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) who was not involved in the Moderna trial. "A lot of times, people are not excited about needles. I mean, who likes getting a shot?" he told Live Science. With the decline in vaccination rates in the United States, a combination vaccine offers more convenience and helps people get on top of their immunization, he said.

The idea of combining multiple immunizations into one shot is not new.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It is a very commonly used strategy, especially in children," said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious-disease doctor at UCSF who was not involved in the study. An example of this is the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is a combination of three vaccines in one shot.

What is in mRNA-1083?

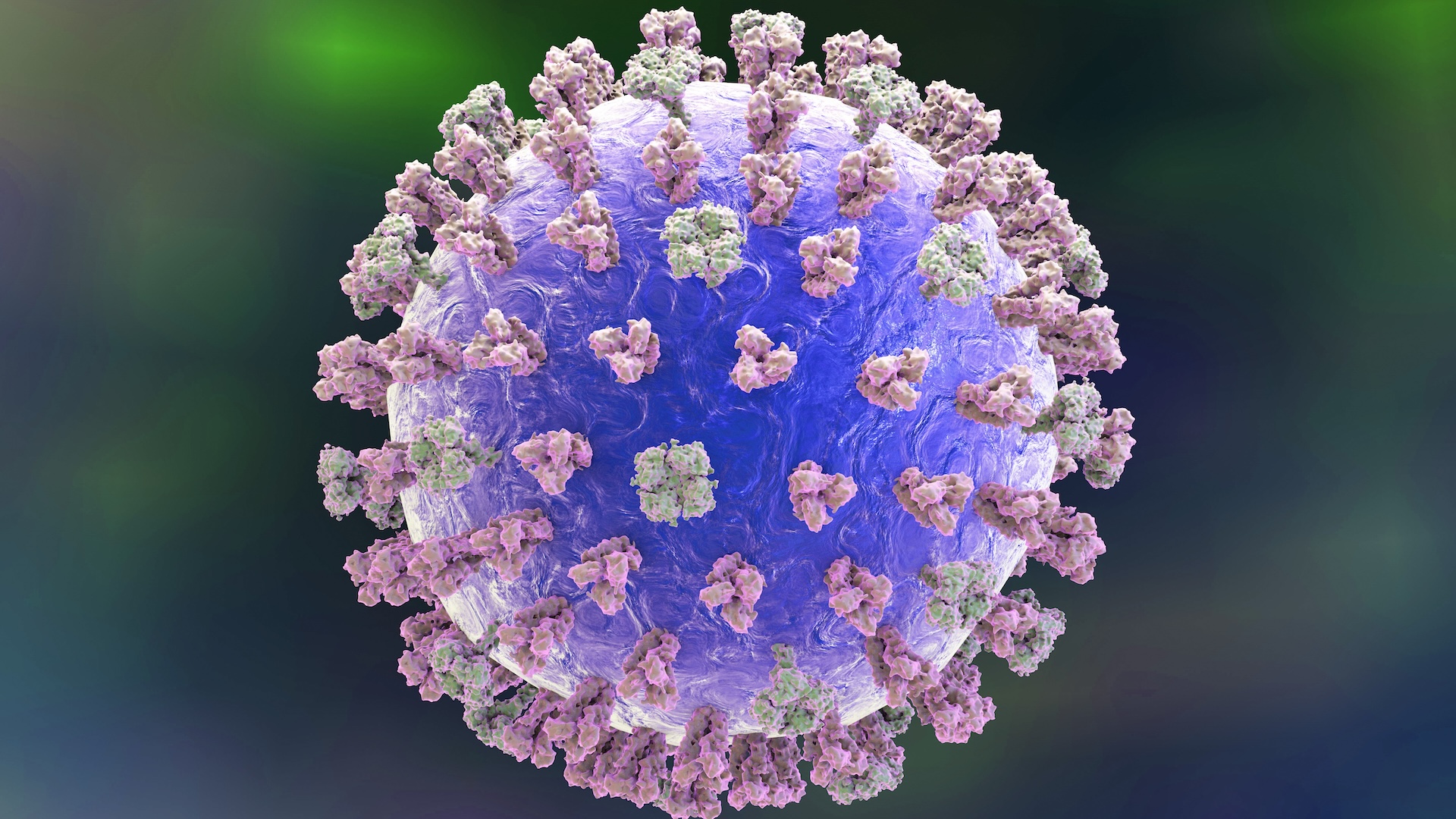

The new mRNA-1083 vaccine is based on the same messenger RNA (mRNA) technology that Moderna used in its FDA-approved vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19. mRNA is a genetic molecule that relays instructions for cells to build different proteins.

The new COVID-flu shot combines the company's updated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, called mRNA-1283, and its newly developed flu vaccine, mRNA-1010. As of yet, there is no FDA-approved flu shot that contains mRNA, so this could be the first.

The culprits behind seasonal flu are influenza A and B viruses, which can be further classified into subtypes and lineages. Current flu vaccines in the U.S. guard against two subtypes of influenza A viruses, called H1N1 and H3N2, and one influenza B virus lineage, known as the Victoria lineage. (Until very recently, the shots also guarded against a second lineage, called "Yamagata," but it's likely extinct.)

The flu component of the new vaccine contains genetic instructions for human cells to make glycoproteins — molecules of protein and carbohydrate — found in these four flavors of influenza A and B viruses. These glycoproteins, known as hemagglutinins (HA), are located on the surface of flu viruses and enable the viruses to latch onto host cells and initiate infection. Once made, these proteins are shown to the immune system so it can recognize the viruses and fight them off.

Likewise, the COVID component of the new vaccine contains the genetic instructions to make the proteins displayed by SARS-CoV-2, called spike proteins.

"mRNA vaccine is the vaccine of the future, particularly when you want to respond to rapidly changing diseases or new variants," Chin-Hong said. Whereas the molecules in mRNA vaccines can be manufactured very quickly as a virus evolves, conventional flu vaccines take months to make. Chin-Hong described mRNA vaccine production as "cutting and pasting a code"; the mRNA that encodes the virus protein can be conveniently incorporated into the platform.

Moderna has already completed Phase 3 clinical trials for the individual flu and COVID components of its new combo vaccine.

On its own, the flu shot triggered higher immune responses than two conventional flu vaccines — Fluarix and the high-dose Fluzone — against A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) strains. It triggered comparable immune responses against influenza B viruses, based on the trial results. Moderna also showed that its new COVID vaccine induced greater immune responses than Spikevax — the FDA-approved shot — against XBB.1.5, a version of the omicron variant that's been circulating recently. Both vaccines were tested on adults ages 18 and older.

How did the combination vaccine perform?

The purpose of Moderna's latest Phase 3 clinical trial was to measure the robustness of the immune response the mRNA-1083 vaccine triggers in people. The trial runners measured this by looking at the number of antibodies vaccinated people produced against both the flu and the SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Real-world data, which would indicate whether the vaccine effectively lowers rates of hospitalization or emergency visits from the infections, is not yet available.

Consistent with these earlier studies on individual vaccines, the mRNA-1083 combination shot triggered a strong immune response against all four influenza viruses and XBB.1.5.

In the trial, the company recruited two groups of participants: one consisting of adults ages 50 to 64, and another including people 65 and older. Each cohort consisted of about 4,000 adults. The 50-to-64-year-olds received either the new combo shot or a combination of Fluarix and Spikevax. The 65-and-older cohort received either mRNA-1083 or a combination of high-dose Fluzone and Spikevax. (Fluzone, a high-dose flu shot, is approved for adults ages 65 and older and some younger people with weakened immune systems.)

The researchers sampled the trial participants' blood at Day 1 and Day 29 of the experiment to measure the levels of antibodies. They found that the mRNA-1083 vaccine triggered a more robust immune response — as reflected in higher levels of antibodies — than the other vaccine combinations against the SARS-CoV-2 variant.

It also triggered a stronger antibody response against all four influenza strains compared with Fluarix, and three influenza subtypes — H1N1, H3N2 and Victoria — compared with Fluzone.

Will the combo vaccine be tested in younger adults?

While the individual components of the new vaccine have been tested in individuals ages 18 to 49, the latest clinical trial for mRNA-1083 did not include this population.

"It was done in people who are at the highest risk of getting in trouble medically [from both the flu and COVID-19]," said Dr. Robert Schooley, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of California, San Diego. "But it doesn't mean that if you're under 50, you don't want to get a booster shot." Everyone 6 months and older is recommended to get an updated COVID-19 shot when new ones become available, typically on an annual basis.

In a recent statement, Moderna announced that the company is deprioritizing further research on mRNA-1083 testing in adults ages 18 to 49. In the same announcement, the company cited an effort to reduce its operational expenses as a factor in the decision. It is unclear if or when the company might resume testing in this age group.

Does the combo shot have more side effects?

Based on the clinical trial results, the likelihood of mild side effects — such as fever, fatigue and chills — was higher with the combination vaccine than with the currently available vaccines given separately.

"These are expected. The side effect is actually your immune system waking up, and likely shows that you'll get a very durable response," Chin-Hong said.

He also added that serious side effects are very uncommon for both the already-approved COVID and flu shots and in the trials of the new combo vaccine. There were no serious side effects related to the new vaccine, the trial runners reported.

When could the vaccine be approved?

Moderna initially applied for FDA approval back in 2024, using the preliminary results from the same Phase 3 trial. At the time, the FDA asked for more data to show efficacy against the flu. With more data in hand, the company is now "targeting approval" for the vaccine in 2026, according to a recent statement.

However, when it comes to mRNA vaccines, both scientific and political factors are at play, Chin-Hong said.

"The science is unmistakable: it [mRNA] is very nimble; it is durable; it is effective in general," he said. But he pointed out that mRNA vaccine technology itself has been the target of political criticism in the U.S. that traces back to the COVID-19 pandemic, when the vaccines' development was expedited and safety concerns were raised. Even though mRNA vaccines have proved to be very safe and effective, this history may pose a barrier to FDA approval of the new combination vaccine, Chin-Hong said.

In addition, the existence of already-approved separate vaccines for flu and COVID-19 may lessen the urgency in getting the mRNA-1083 approved, he added.

Research funding through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has been widely cut or frozen, and research on vaccine hesitancy and the boosting of vaccination rates was specifically affected. Experts told NPR that they're concerned mRNA research will soon face similar cuts. NIH officials were cautioned to keep the term "mRNA" out of grant applications, KFF reported.

There are also uncertainties about whether mRNA-1083 will be subject to the new framework on vaccine approval. On May 1, a Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson told The Washington Post that "all new vaccines will undergo safety testing in placebo-controlled trials prior to licensure." A placebo is an inert or inactive substance, such as a saline shot, that new vaccines would have to be compared against during a clinical trial.

Many trials of brand-new vaccines already include placebos. But when there are already existing and effective vaccines for a given disease, comparing a new shot against a placebo isn't necessarily helpful or ethical. Scientists want to understand how much better the new shot works compared with the previous one.

"I don't think it's ethical to give someone a shot that is a placebo, that can in no way help them, when you know there's an existing technology that can," said Dr. Paul Offit, a virologist, immunologist and director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Because mRNA-1083 is a modified version of an already-approved vaccine, "I'm not sure whether that counts as new," Offit said. He thinks a placebo-controlled trial would not be appropriate in this case.

Although the new combo shot still awaits approval, Gandhi said the current clinical trial results were "already convincing." The Phase 3 clinical trial demonstrated that the vaccine is safe and triggers a robust immune response, she added.

"I don't see any red flags at this point," Schooley said. "I'd be confident to take the vaccine myself."

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Kristel is a science writer based in the U.S. with a doctorate in chemistry from the University of New South Wales, Australia. She holds a master's degree in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work has appeared in Drug Discovery News, Science, Eos and Mongabay, among other outlets. She received the 2022 Eric and Wendy Schmidt Awards for Excellence in Science Communications.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus