You may not really be allergic to penicillin. Here's how to find out if you are.

As many as 1 in 5 Americans believe they have a penicillin allergy, but just a tiny fraction actually do. In recent years, it's gotten a lot easier to find out.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Imagine this: You're at your doctor's office with a sore throat. The nurse asks, "Any allergies?" And without hesitation you reply, "Penicillin." It's something you've said for years — maybe since childhood, maybe because a parent told you so. The nurse nods, makes a note and moves on.

But here's the kicker: There's a good chance you're not actually allergic to penicillin. About 10% to 20% of Americans report that they have a penicillin allergy, yet fewer than 1% actually do.

I'm a clinical associate professor of pharmacy specializing in infectious disease. I study antibiotics and drug allergies, including ways to determine whether people have penicillin allergies.

I know from my research that incorrectly being labeled as allergic to penicillin can prevent you from getting the most appropriate, safest treatment for an infection. It can also put you at an increased risk of antimicrobial resistance, which is when an antibiotic no longer works against bacteria.

The good news? It's gotten a lot easier in recent years to pin down the truth of the matter. More and more clinicians now recognize that many penicillin allergy labels are incorrect — and there are safe, simple ways to find out your actual allergy status.

A steadfast lifesaver

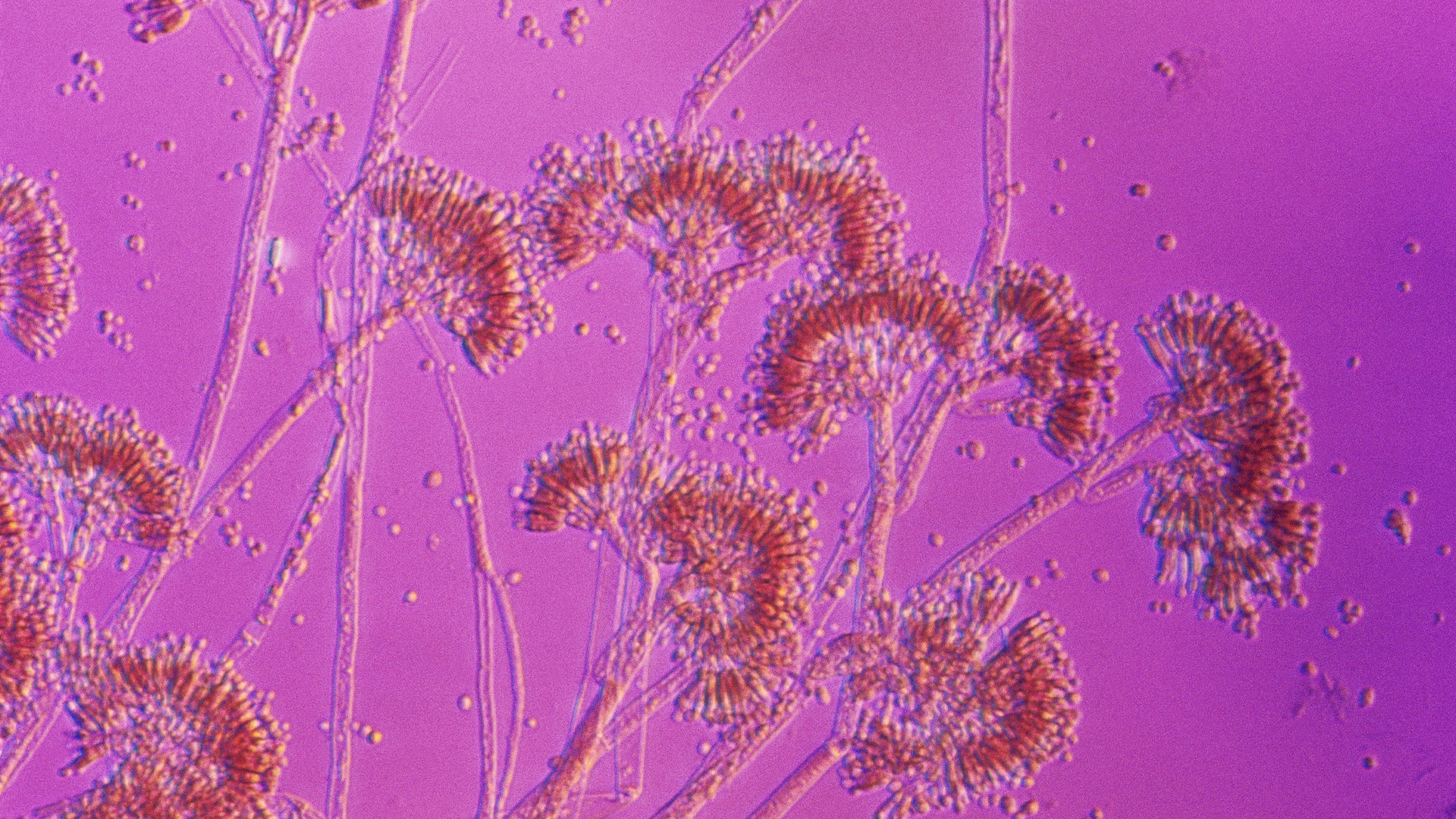

Penicillin, the first antibiotic drug, was discovered in 1928 when a physician named Alexander Fleming extracted it from a type of mold called penicillium. It became widely used to treat infections in the 1940s. Penicillin and closely related antibiotics such as amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, which goes by the brand name Augmentin, are frequently prescribed to treat common infections such as ear infections, strep throat, urinary tract infections, pneumonia and dental infections.

Related: Mold that led to penicillin discovery revived to fight superbugs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Penicillin antibiotics are a class of narrow-spectrum antibiotics, which means they target specific types of bacteria. People who report having a penicillin allergy are more likely to receive broad-spectrum antibiotics. Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill many types of bacteria, including helpful ones, making it easier for resistant bacteria to survive and spread. This overuse speeds up the development of antibiotic resistance. Broad-spectrum antibiotics can also be less effective and are often costlier.

Why the mismatch?

People often get labeled as allergic to antibiotics as children when they have a reaction such as a rash after taking one. But skin rashes frequently occur alongside infections in childhood, with many viruses and infections actually causing rashes. If a child is taking an antibiotic at the time, they may be labeled as allergic even though the rash may have been caused by the illness itself.

Some side effects such as nausea, diarrhea or headaches can happen with antibiotics, but they don't always mean you are allergic. These common reactions usually go away on their own or can be managed. A doctor or pharmacist can talk to you about ways to reduce these side effects.

People also often assume penicillin allergies run in families, but having a relative with an allergy doesn't mean you're allergic — it's not hereditary.

Finally, about 80% of patients with a true penicillin allergy will lose the allergy after about 10 years. That means even if you used to be allergic to this antibiotic, you might not be anymore, depending on the timing of your reaction.

Why does it matter if I have a penicillin allergy?

Believing you're allergic to penicillin when you're not can negatively affect your health. For one thing, you are more likely to receive stronger, broad-spectrum antibiotics that aren't always the best fit and can have more side effects. You may also be more likely to get an infection after surgery and to spend longer in the hospital when hospitalized for an infection. What's more, your medical bills could end up higher due to using more expensive drugs.

Penicillin and its close cousins are often the best tools doctors have to treat many infections. If you're not truly allergic, figuring that out can open the door to safer, more effective and more affordable treatment options.

How can I tell if I am really allergic to penicillin?

Start by talking to a health care professional such as a doctor or pharmacist. Allergy symptoms can range from a mild, self-limiting rash to severe facial swelling and trouble breathing. A health care professional may ask you several questions about your allergies, such as what happened, how soon after starting the antibiotic did the reaction occur, whether treatment was needed, and whether you've taken similar medications since then.

These questions can help distinguish between a true allergy and a nonallergic reaction. In many cases, this interview is enough to determine you aren't allergic. But sometimes, further testing may be recommended.

One way to find out whether you're really allergic to penicillin is through penicillin skin testing, which includes tiny skin pricks and small injections under the skin. These tests use components related to penicillin to safely check for a true allergy. If skin testing doesn't cause a reaction, the next step is usually to take a small dose of amoxicillin while being monitored at your doctor's office, just to be sure it's safe.

A study published in 2023 showed that in many cases, skipping the skin test and going straight to the small test dose can also be a safe way to check for a true allergy. In this method, patients take a low dose of amoxicillin and are observed for about 30 minutes to see whether any reaction occurs.

With the right questions, testing and expertise, many people can safely reclaim penicillin as an option for treating common infections.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elizabeth W. Covington is a professor in the department of pharmacy practice at Auburn University Harrison College of Pharmacy. She obtained a bachelor of science degree in chemistry from Furman University in 2012 and completed her doctor of pharmacy at the Harrison College of Pharmacy in 2016. She went on to complete an ASHP-accredited post-graduate residency at DCH Regional Medical Center in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. In 2019, she became a Board-Certified Infectious Disease Pharmacist. Dr. Covington’s expertise includes antimicrobial stewardship and infectious diseases, with particular emphasis on improving antibiotic prescribing in transitions of care and antibiotic allergies.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus