Coronavirus variants: Facts about omicron, delta and other SARS-CoV-2 mutants

Here's a look at the science behind SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the now-dominant omicron and its many defunct relatives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

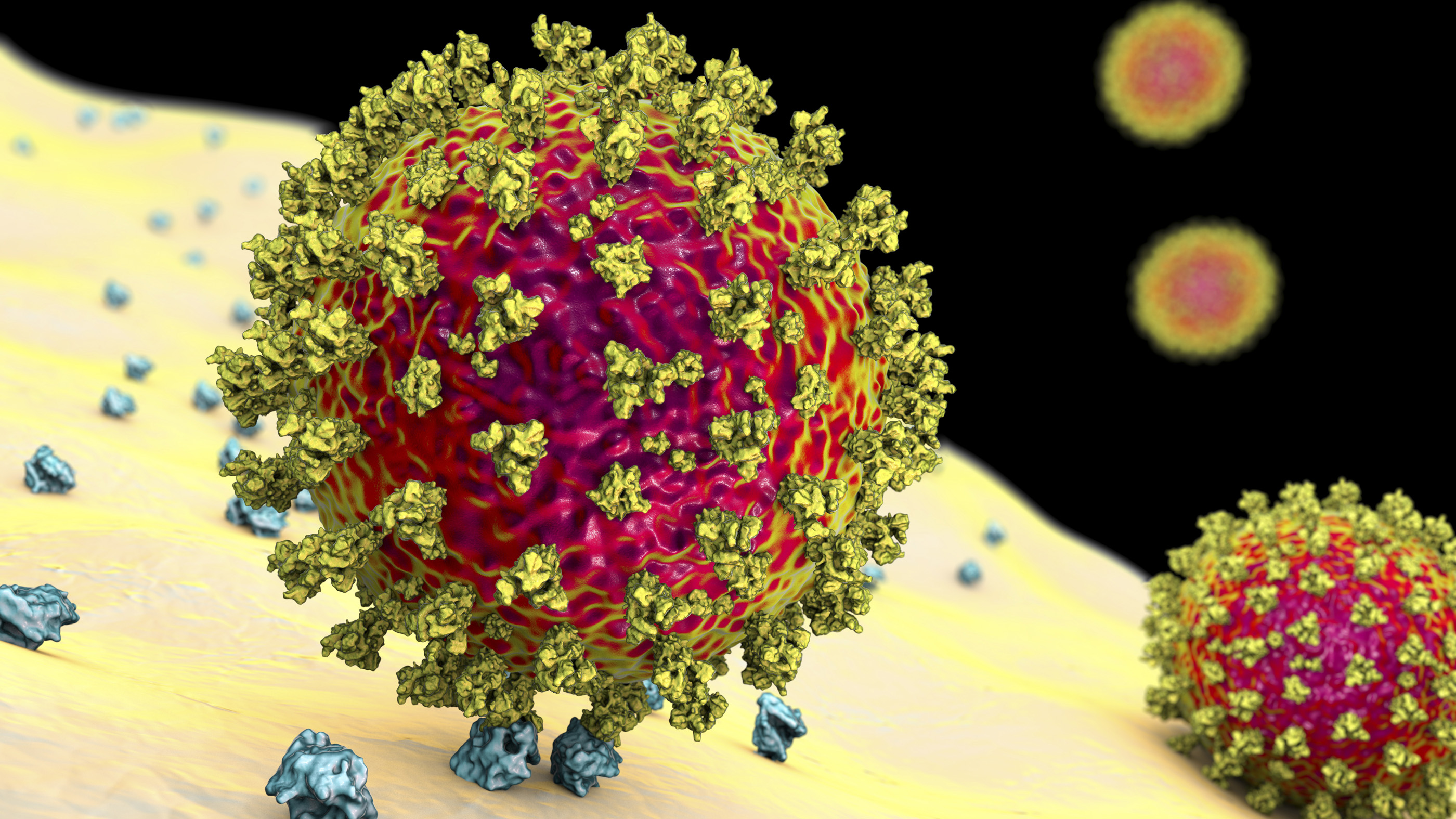

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the pathogen has given rise to a slew of descendants.

By picking up mutations in their genetic code, some of these descendants, known as coronavirus variants, have gained the ability to spread more easily between people, outwit the immune system or trigger more severe disease. These abilities give the variants a competitive edge over their relatives, and in time, the advantaged variants outcompete the disadvantaged for hosts and eventually drive them to extinction.

The omicron variant first emerged in November 2021 and gained global prominence in March 2022. And as of August 2023, the direct descendents of omicron — known as omicron subvariants — only have each other left to compete against, as all other versions of the coronavirus have dwindled away.

The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants in three categories: variants of concern (VOC), variants of interest (VOI) and variants under monitoring (VUM). As of March 15, 2023, there are no circulating VOCs, and all the VOIs and VUMs are different subvariants of omicron.

Related: Do other viruses have as many variants as SARS-CoV-2?

Here's a look at the science of the SARS-CoV-2 variants, including both omicron and past variants that have fallen from prominence.

Currently circulating variants

Omicron variant (B.1.1.529)

Where did the variant emerge? The original version of omicron, formally known as B.1.1.529, was first identified in South Africa in November 2021. The WHO labeled omicron as a variant of concern on Nov. 26, 2021, but it's since been downgraded.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Where is it now? Omicron quickly spread around the world, causing a surge of COVID-19 cases in December 2021 and January 2022. By mid-March 2022, omicron was the dominant coronavirus variant in the world, accounting for 99.9% of coronavirus genome sequences from recent COVID-19 cases in the global database GISAID.

What are key mutations? The original version of omicron had more than 30 mutations in the genes that code for its spike protein, with 10 of those genes coding for parts of the "receptor binding domain," or the part of the spike protein that latches onto human cells.

Some of omicron's other mutations have also shown up in previous variants of concern. For example, omicron has the N501Y mutation, which is also found in the alpha variant, and is thought to make the virus more contagious, according to The New York Times.

The original omicron, B.1.1.529, has since fallen out of circulation, but not before spawning dozens of its own descendents. Each of these offspring comes with its own genetic quirks.

As of August, the WHO's list of VOIs includes XBB.1.5 and XBB.1.16, two branches that stem from the broader XBB lineage of omicron. The majority of VUM are also XBB subvariants, with the exception of BA.2.75 and its offspring CH.1.1.

Why is the variant concerning? Omicron has many mutations in the spike protein that appear to make it more transmissible and allow it to at least partially evade vaccines. Some studies estimated that omicron's BA.1 subvariant is four times more transmissible than the delta variant, according to CNBC. And BA.2 is more contagious still — it's estimated to be 1.5 times more transmissible than BA.1, CNBC reported.

Do vaccines work? Most COVID-19 vaccines, including those used in the U.S., prime the immune system against the spike protein. Because of the high number of mutations that omicron has on its spike protein, scientists expected that vaccines would be less effective against omicron compared with previous variants.

And indeed, there has been an increased number of breakthrough infections with omicron compared with earlier variants. A study published in March in The New England Journal of Medicine found that the vaccine effectiveness of two doses of the Pfizer vaccine was 65%, but this fell to about 9% more than 25 weeks after vaccination. However, with an additional vaccine dose, the shot's effectiveness rose to 67%, and then fell to about 45% after about 10 weeks, the researchers found. A CDC report published in January 2022 also found that an extra dose provided 90% protection against hospitalization with omicron.

In fall 2022, two updated COVID-19 vaccines were released that targeted the omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.5, as well as the original version of SARS-CoV-2. At the time, these two flavors of omicron were responsible for the majority of new COVID-19 cases in the U.S. In 2023, the vaccines will get another update, this time to guard against the XBB lineage of omicron, whose members are currently causing the majority of cases.

(The XBB lineage includes EG.5, which started dominating in the U.S. in late July 2023.)

Previously circulating variants

The following information was last updated in March 2022. Previous sections of this article were last updated in August 2023.

Delta variant (B.1.617.2)

Where did the variant emerge? The delta variant, formerly called B.1.617.2, was first identified in India in October 2020 and labeled as a variant of concern in May 2021, according to the WHO.

Where is it now? Delta rapidly became the dominant variant in the U.S. and worldwide in the summer of 2021, but it would largely be replaced by omicron in mid-December 2021, according to Yale Medicine. Besides omicron, delta remains the only other VOC with a notable level of global circulation, according to WHO. By mid-March 2022, delta accounted for 0.1% of coronavirus genome sequences from recent COVID-19 cases in the global database GISAID.

What are key mutations? The delta variant has several important mutations in the spike protein, including T19R, del157/158, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N mutations, according to outbreak.info. Two of these mutations — L452R and D614G — allow the variant to attach more firmly to ACE2 receptors, Live Science previously reported. Others, such as P681R, may allow delta to evade host immunity.

Why is the variant concerning? The delta variant is potentially up to 60% more transmissible than the alpha variant and perhaps twice as transmissible as the original strain of coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China. In addition, some evidence suggests the variant can more easily evade existing vaccines than earlier variants of the coronavirus.

Do vaccines work? All the vaccines approved in the U.S. likely work against the delta variant, although exactly how well still isn't clear. For instance, Public Health England found the Pfizer vaccine was 88% effective against the delta variant, while health officials in Israel announced the Pfizer vaccine was only 64% effective against delta, The New York Times reported. However, Israel didn't control for differences in people who did and did not get vaccinated, making its data hard to interpret, according to The New York Times. The Pfizer vaccine remained strongly protective against severe disease and hospitalization. In a statement, Moderna said its vaccine neutralized the delta variant, and though it has not yet provided real-world data on infection, it is likely to work similarly to the Pfizer mRNA vaccine. Johnson & Johnson said their vaccine produced a strong neutralizing antibody response against the delta variant, but did not report on how much it reduces the odds of symptomatic disease, Live Science previously reported.

Alpha variant (B.1.1.7)

Where did the variant emerge? The alpha variant, formerly called B.1.1.7, was first seen in the United Kingdom in September 2020, according to WHO(WHO). By December 2020, the variant had shown up in the United States.

Where is it now? Alpha is virtually extinct worldwide. After its emergence in the U.K., the alpha variant soon spread around the world, and became the dominant variant in the U.S. in the spring of 2021, according to The New York Times. But the delta variant replaced alpha as the dominant strain in the U.S. in the summer of 2021, the Times reported. Cases of the alpha variant have since faded in the U.S. and worldwide. By March 2022, few to no genetic sequences from alpha had been reported worldwide, and the variant was designated a "previously circulating VOC," according to WHO.

What are key mutations? The alpha variant has 23 mutations compared with the original Wuhan strain, with eight of those in the virus's spike protein, according to the American Society for Microbiology. (ASM) Three of the spike-protein mutations are thought to be responsible for the biggest impact on the virus's biology: The N501Y mutation seems to boost how tightly the spike protein attaches to the ACE2 receptors — the main entry point into human cells; the 69-70del mutation could, in concert with N501Y, explain the variant's increased transmissibility, some scientists say; and the P681H mutation could also increase transmissibility, as it may be involved in how the virus merges its membrane with that of a human cell in order to deliver its genome into the cell, according to ASM.

Why is the variant concerning? The strain is about 50% more transmissible than the original form of the novel coronavirus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Do vaccines work? Research to date suggests that the two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna vaccines) are effective at preventing symptomatic infections with the alpha variant of the coronavirus. For instance, a study published June 28, 2021 in the journal Nature Communications found that the blood of health care workers who had been vaccinated with the Pfizer shot was effective at neutralizing B.1.1.7. A single dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine also stimulates neutralizing antibodies that protect against the alpha variant, J&J reported in July, 2021.

Beta variant (B.1.351)

Where did the variant emerge? The beta variant, formerly called B.1.351, was first detected in South Africa in October 2020 and was designated a variant of concern in December 2020, according to WHO.

Where is it now? Beta is also nearly extinct. It took off rapidly in South Africa in late 2020 and early 2021, and spread to over 30 countries, Live Science previously reported. But beta was never common in the U.S., and it was later replaced by delta in the places where it was once dominant, according to Nature News. Beta was also designated a "previously circulating VOC" in March 2022, according to WHO..

What are key mutations? The beta variant has eight distinct mutations that may affect how the virus binds to cells, Live Science previously reported. The most notable are N501Y, K417N and E484K. The N501Y mutation, also seen in the alpha variant, may allow the novel coronavirus to bind more tightly to the ACE2 receptor. The K417N mutation may change the shape of the spike protein, making antibodies primed for earlier strains less likely to recognize the spike. The third notable mutation, E484K, also seems to help the virus evade antibodies from the immune system, according to a February 2021 study in the British Medical Journal.

Why is the variant concerning? The beta variant is about 50% more transmissible than the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 that emerged in Wuhan, according to the CDC. Some monoclonal antibodies don't work as well against the strain, according to the CDC. Vaccines are also less effective against the variant. And the variant may lead to slightly more severe disease and slightly higher risk of death than the original coronavirus, according to a July 2021 study in The Lancet Global Health.

Do vaccines work? Most vaccines work with lower efficacy against beta than was seen for earlier strains. For instance, the Pfizer vaccine had a 75% efficacy against the beta variant, which is lower than the 95% efficacy seen in clinical trials when earlier strains were dominant, according to a May 2021 study in The New England Journal of Medicine. The Johnson & Johnson and Novavax vaccines also showed lower efficacy against the beta variant. And the AstraZeneca vaccine did not prevent mild or moderate COVID-19 in trials in South Africa when beta was the dominant strain, according to the Global Virus Network. Data on how well the Moderna shot works against the beta variant is limited, but most experts suspect it will work similarly to Pfizer's mRNA vaccine.

Gamma variant (P.1)

Where did the variant emerge? The earliest documented samples of the gamma variant, also known as P.1, were collected in Brazil in November 2020, according to the WHO. Scientists first found the variant in Japan in early January 2021, when four travelers tested positive for the virus after a trip to Brazil; researchers then found evidence that the variant was already widespread in the South American country, The New York Times reported. Gamma was labeled as a variant of concern on Jan. 11, 2021.

Where is it? Gamma is no longer circulating widely. In July, 2021, gamma had been reported in 74 countries worldwide, according to the United Nations. But cases faded with the rise of delta and omicron, with few to no genetic sequences from gamma reported worldwide by March 2022, according to WHO. Gamma was also designated a "previously circulating VOC" in March 2022.

What are key mutations? Gamma is closely related to beta (B.1.351), and the two variants share some of the same mutations in their spike proteins, the Times reported. These spike protein mutations include N501Y, which helps the virus bind tightly to cells and is also found in the alpha (B.1.1.7) lineage. The spike mutation K417T may also help gamma latch onto cells, while the E484K mutation likely helps the variant dodge certain antibodies. And according to the CDC, in addition to these three mutations, the variant carries eight additional sequence changes in its spike: L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, D614G, H655Y and T1027I.

Why is the variant concerning? Several studies suggest that gamma is about twofold more transmissible than its parent coronavirus lineage, B.1.1.28, and that gamma infections are associated with a significantly higher viral load than other variants. Compared with the original strain of SARS-CoV-2, gamma shows less susceptibility to several monoclonal antibody treatments, including bamlanivimab and etesevimab, according to the CDC. And according to a study, published May 12, 2021 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, the variant also appears relatively resistant to neutralization by convalescent plasma and antibodies drawn from vaccinated people.

Do vaccines work? Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine produces neutralizing antibodies against gamma, although the shot is slightly less effective against the variant than it is against the original strain of the virus, the company announced on June 29. The Pfizer vaccine showed similar levels of protection against gamma in a recent study, Business Insider reported; and the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine also produces neutralizing antibodies against the variant, according to a recent statement from the company.

Lambda variant (C.37)

Where did the variant emerge? The lambda variant, also known as C.37, was first detected in Peru in August 2020, according to WHO. On June 14, 2021, WHO designated C.37 a global variant of interest, and dubbed it lambda.

Where is it now? Lambda spread to a number of countries in the summer of 2021 and had high levels of spread in Peru and Chile, Live Science previously reported. But by March 2022, there was no circulation of the variant reported worldwide in the past 90 days, according to WHO.

What are key mutations? The variant has seven mutations in the virus's spike protein compared with the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 detected in Wuhan. Specifically, these mutations are known as G75V, T76I, del247/253, L452Q, F490S, D614G and T859N, according to the WHO.

Why is the variant concerning? Some of these mutations have the potential to increase transmissibility of the virus or to reduce the ability of certain antibodies to neutralize, or inactivate, the virus. For example, lambda has a mutation known as F490S located in the spike protein's receptor-binding domain (RBD), where the virus first docks onto human cells. A paper published in the July 2021 issue of the journal Genomics identified F490S as a likely "vaccine escape mutation" that could both make the virus more infectious and disrupt the ability of vaccine-generated antibodies to recognize the variant.

Do vaccines work? Data from the time when lambda was circulating did not show that the lambda variant caused more severe disease or reduced vaccine effectiveness, according to Public Health England.

Mu variant (B.1.621)

Where did the variant emerge? The mu variant, also known as B.1.621, was first detected in Colombia in January 2021, according to the WHO. On Aug. 30, WHO classified it as a "variant of interest," and named it mu.

Where is it now? The mu variant caused some large outbreaks in South America and Europe in 2021, according to the WHO. But the mu variant did not out-compete the delta variant in terms of circulation, and by March 2022, there was no circulation of the variant reported worldwide in the past 90 days, according to WHO.

What are key mutations? Mu shares some concerning mutations with the beta variant, including mutations known as E484K and K417N, according to Medpage Today.

Why is the variant concerning? The mu variant "has a constellation of mutations that indicate potential properties of immune escape," WHO officials said in August 2021. Early data in lab dishes show that antibodies generated in response to COVID-19 vaccination or previous infection are less able to "neutralize," or bind to and disable, the mu variant, the report said. However, this finding still needs to be confirmed by future studies.

Do vaccines work? According to Public Health England, there is "no real-world data on vaccine effectiveness" against mu. Studies in lab dishes have found a reduction in the ability of antibodies to neutralize the mu variant that is "at least as great as that seen with the beta variant," according to Public Health England.

Jeanna Bryner, Tia Ghose and Yasemin Saplakoglu contributed to this article.

Editor's note: The introduction and omicron sections of this page were last updated on Aug. 8, 2023. The information about previously circulating variants was last updated on March 23, 2022.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus