Rare clotting effect of early COVID shots finally explained — what could that mean for future vaccines?

Scientists have offered a new explanation for why COVID-19 vaccines that contained adenoviruses carried a rare-but-serious risk of blood clotting.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Rare blood clots tied to some early COVID-19 vaccines that are no longer in use may have been the result of two out-of-control immune reactions happening at once.

One of these immune reactions was already known, but the second, reported Oct. 26 in the journal Blood, is a new discovery.

The finding could help to explain how other clotting conditions develop and point to better treatments, as well as suggest ways to make vaccines safer for people who are prone to the side effect.

"Understanding how a drug causes an adverse event allows us to design new approaches to make those treatments safer," said Ishac Nazy, an associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Canada who studies the vaccine-related clotting disorder but was not involved in the current research.

A rare side effect

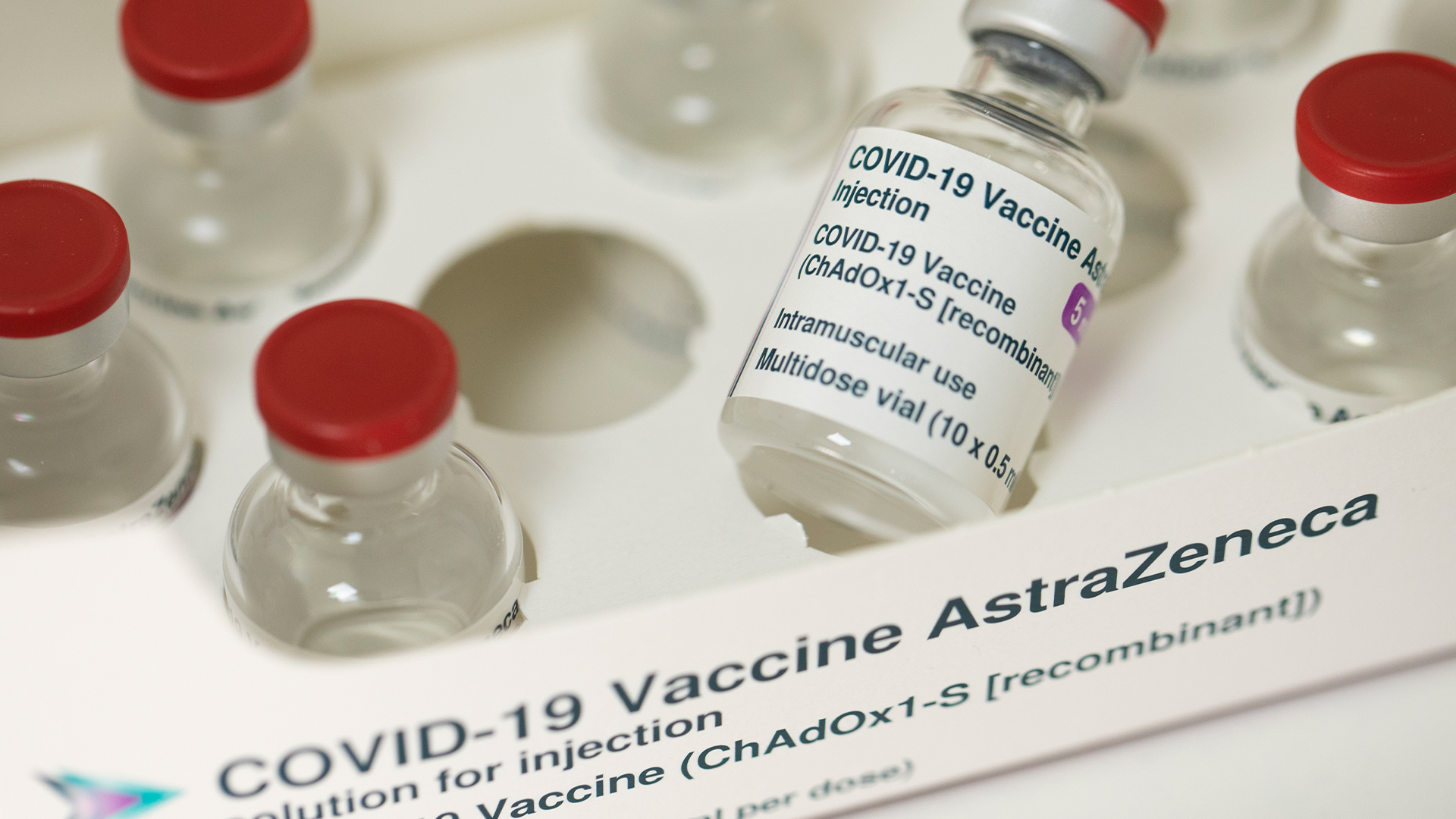

The vaccine-related clotting disorder, known as vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), was rare and linked to two shots: the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. Both shots contained common-cold viruses called adenoviruses that were tweaked so that they couldn't infect cells. Instead, the modified viruses carried DNA instructions for part of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, into the body.

VITT was a sobering side effect of what many public health experts had hoped would be a promising technology. Unlike the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 shots, which contain RNA, the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines did not need ultracold storage, making them more accessible where cold-chain storage is unreliable. Adenovirus-based vaccines have been investigated for other diseases, but very few have achieved approval. Exceptions are an adenovirus-based Ebola vaccine approved in China and another approved by the European Union, both used only in at-risk individuals.

Soon after rolling out the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines, doctors began reporting cases of clotting that looked a lot like a previously known disorder called Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). About 20 to 30 years ago, HIT affected 3.5% of patients who had knee or hip replacements, said Dr. Andreas Greinacher, a physician who specializes in clotting disorders at the Greifswald University Hospital in Germany and was not involved in the new research. In these patients, heparin, a blood thinner normally given to prevent blood clots, actually triggered runaway clotting instead.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The adenovirus-based COVID vaccines were triggering the same condition as HIT, though scientists gave it a new acronym to reflect the different origin. Researchers reported that about 1 in 50,000 people under 50 who received the vaccine were affected, as well as about 1 in 100,000 of those 50 and older.

Neither vaccine is currently administered in the U.S. (AstraZeneca's shot was never used in the country, and J&J's vaccine was authorized but then retired due to the clotting issue and availability of better vaccines.) However, learning what triggers VITT could still be useful.

Today, HIT is rare because doctors now understand what causes it and can prescribe different, safer versions of heparin, Greinacher told Live Science. Similarly, he said, studying the mechanisms behind HIT and VITT could make adenovirus vaccines safer.

"Our big aim currently is to find which factor in the vaccines is triggering it," Greinacher said. "If you know the factor, I'm certain there are very smart biotechnologists who can modify the adenovirus vector so this factor is no longer present."

Unraveling VITT

When VITT was first observed in patients getting COVID-19 vaccines in February 2021, scientists soon discovered that it had to do with PF4, a chemical signal released by platelets, the blood cells that form clots.

In rare cases after vaccination with an adenovirus-based vaccine, the body would make antibodies to PF4. These antibodies would latch onto PF4 and form clumps that could then bind to receptors called Fc on other platelets. This would activate the platelets and lead to a runaway clotting response.

The new Blood study found that PF4 alone also activates a second set of receptors that cause platelets to accumulate, likely a second reason why clotting goes haywire in this disorder.

There is still a long way to go, Nazy told Live Science, whose team first reported in 2021 how antibodies against PF4 were causing VITT. The new research suggests that there are actually two different ways that PF4 acts in VITT, he said. These two pathways are not exclusive and may work in tandem.

In the new study, researchers tested blood from healthy individuals and people with VITT to trace the cascade of signals that leads to the overactive clotting. They found that the PF4 activates a receptor called c-Mpl on platelets, which causes them to clump together. This is in addition to the mechanism discovered in 2021, in which complexes of PF4 and PF4 antibodies activate platelets' Fc receptors.

"What we have shown is that as well as that antibody trigger, you've also got PF4 itself binding to platelets and activating them, providing a double whammy," Phillip Nicolson, an associate clinical professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Birmingham in the U.K. and the leader of the new study, told Live Science. "That may be why [the clotting] happens to a harmful degree."

Scientists have a few clues as to why adenovirus vaccines can trigger this response. PF4 carries a positive electrical charge on its surface, while adenoviruses are highly negatively charged, Nicolson said, so they may bind together easily. But even that is not confirmed, Nazy said, and has mostly been shown with computer modeling rather than with real molecules.

In rare cases, unusual clotting happens without vaccination or treatment with heparin. A recent paper published in the The New England Journal of Medicine, and co-authored by Nazy, found that in at least two of these unexplained clotting cases, the clotting disorder occurred after typical adenovirus infections. In many cases, the connection between unexplained clotting and a viral infection may be missed. And it's still a mystery why very few people are susceptible to these clotting conditions.

"That's the part we need to understand to prevent the disease from even happening," Nazy said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus