Gray hair may have evolved as a protection against cancer, study hints

Aging comes with graying hair, which may be a sign of the body lowering its risk of cancer, a study suggests.

Graying hair could be a sign that the body is effectively protecting itself from cancer, a new study suggests.

Cancer-causing triggers, such as ultraviolet (UV) light or certain chemicals, activate a natural defensive pathway that leads to premature graying but also reduces the incidence of cancer, the research found.

The researchers behind the study tracked the fate of the stem cells responsible for producing the pigment that gives hair its color. In mouse experiments, they found that these cells responded to DNA damage either by ceasing to grow and divide — leading to gray hair — or by replicating uncontrollably to ultimately form a tumor.

The findings, reported in October in the journal Nature Cell Biology, underline the importance of these sorts of protective mechanisms that emerge with age as a defense against DNA damage and disease, the study authors say.

Graying hair as cancer defense

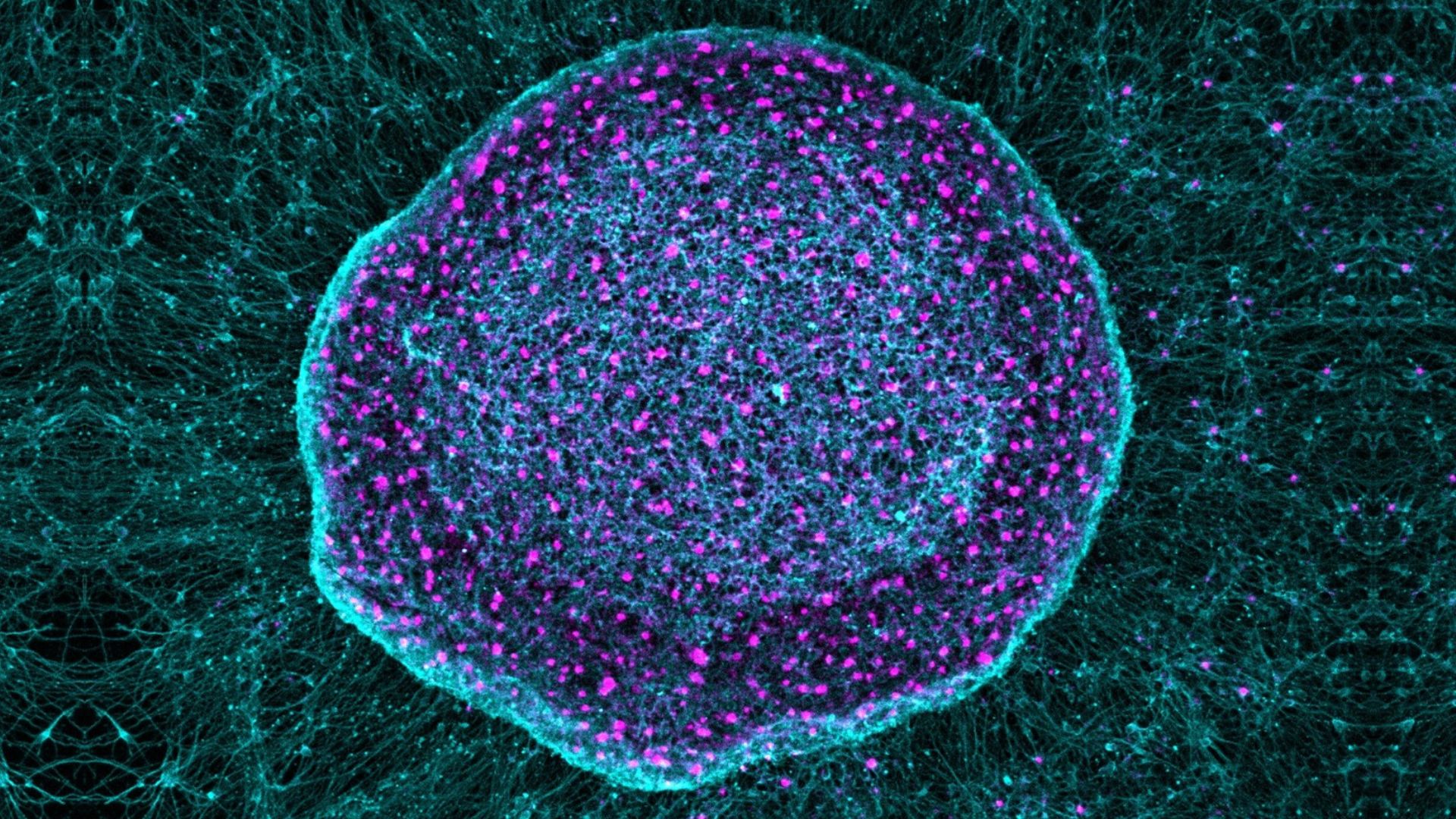

Healthy hair growth is dependent on a population of stem cells that constantly renews itself within the hair follicle. A tiny pocket within the follicle contains reserves of melanocyte stem cells — precursors to the cells that produce the melanin pigment that gives hair its color.

"Every hair cycle, these melanocyte stem cells will divide and produce some mature, differentiated cells," said Dot Bennett, a cell biologist at City St George's, University of London who was not involved in the study. "These migrate down to the bottom of the hair follicle and start making pigment to feed into the hair."

Graying occurs when these cells can no longer produce sufficient pigment to thoroughly color each strand.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's a sort of exhaustion called cell senescence," Bennett explained. "It's a limit to the total number of divisions that a cell can go through, and it seems to be an anti-cancer mechanism to prevent random genetic errors acquired over time propagating uncontrollably."

When the melanocyte stem cells reach this "stemness checkpoint," they cease to divide, meaning the follicle no longer has a source of pigment to color the hair. Ordinarily, this occurs with old age as the stem cells naturally reach this limit. However, Emi Nishimura, a professor of stem cell age-related medicine, and colleagues at the University of Tokyo were interested in how this same mechanism operates in response to DNA damage — a key trigger for cancer development.

In mouse studies, the team used a combination of techniques to track the progress of individual melanocyte stem cells through the hair cycle after exposing them to different harmful environmental conditions, including ionizing radiation and carcinogenic compounds. Intriguingly, they found that the type of damage influenced how the cell reacted.

Ionizing radiation caused the stem cells to differentiate and mature, and ultimately activated the biochemical pathway responsible for cell senescence. As a result, the melanocyte stem cell reserves were rapidly depleted over the hair cycle, thus halting the production of further mature pigment cells and leading to gray hair.

Meanwhile, by essentially switching off cell division, this senescence pathway prevented the mutated DNA from passing into a new generation of cells, thus lowering the likelihood of those cells forming cancerous tumors.

Exposure to chemical carcinogens — such as 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), a tumour initiator widely used in cancer research — appeared to bypass this protective mechanism. Instead of switching on senescence, it toggled on a competing cellular pathway.

This alternative chemical sequence blocked cell senescence in the team's mouse studies, enabling the hair follicles to retain their stem cell reserves and the ability to produce pigment, even after DNA damage. That meant that the hair retained its color, but in the long term, the unchecked replication of damaged DNA led to tumor formation and cancer, the team said in a statement.

These findings reveal that the same stem cell population can meet opposite fates depending on the type of stress they're exposed to, lead study author Nishimura said in the statement. "It reframes hair graying and melanoma [skin cancer] not as unrelated events, but as divergent outcomes of stem cell stress responses," Nishimura added.

The next step will be to translate this understanding into human hair follicles, to see whether these observations in mice carry over to people, Bennett said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Victoria Atkinson is a freelance science journalist, specializing in chemistry and its interface with the natural and human-made worlds. Currently based in York (UK), she formerly worked as a science content developer at the University of Oxford, and later as a member of the Chemistry World editorial team. Since becoming a freelancer, Victoria has expanded her focus to explore topics from across the sciences and has also worked with Chemistry Review, Neon Squid Publishing and the Open University, amongst others. She has a DPhil in organic chemistry from the University of Oxford.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus