Psychedelics may rewire the brain to treat PTSD. Scientists are finally beginning to understand how.

New research shows MDMA and psilocybin may restore neural flexibility in people with PTSD, thereby helping the brain unlearn fear and relearn safety.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This story includes discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, the national suicide and crisis lifeline in the U.S. is available by calling or texting 988. There is also an online chat at 988lifeline.org.

For researcher Lynnette Averill, the quest to find a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is deeply personal. Averill's father served as an enlisted infantryman with the U.S. Marine Corps in Vietnam and struggled to cope with his war experiences when he returned home. After years of ineffective treatments, he died by suicide when Averill was three.

Driven by a mission to support veterans' mental health, Averill trained as a psychologist and began working with people with PTSD — a condition that affects more than 12 million Americans in any given year. Victims of violence, abuse and accidents can experience post-traumatic symptoms such as persistent flashbacks, hypervigilance, and entrenched negative beliefs about themselves and their environment.

"People can be very stuck in black-and-white thinking, such as, 'I'm a bad person,' 'I deserve this,' 'the world is dangerous," Averill, a clinical research psychologist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, said during a panel discussion at the Psychedelic Science conference in Denver in June 2025.

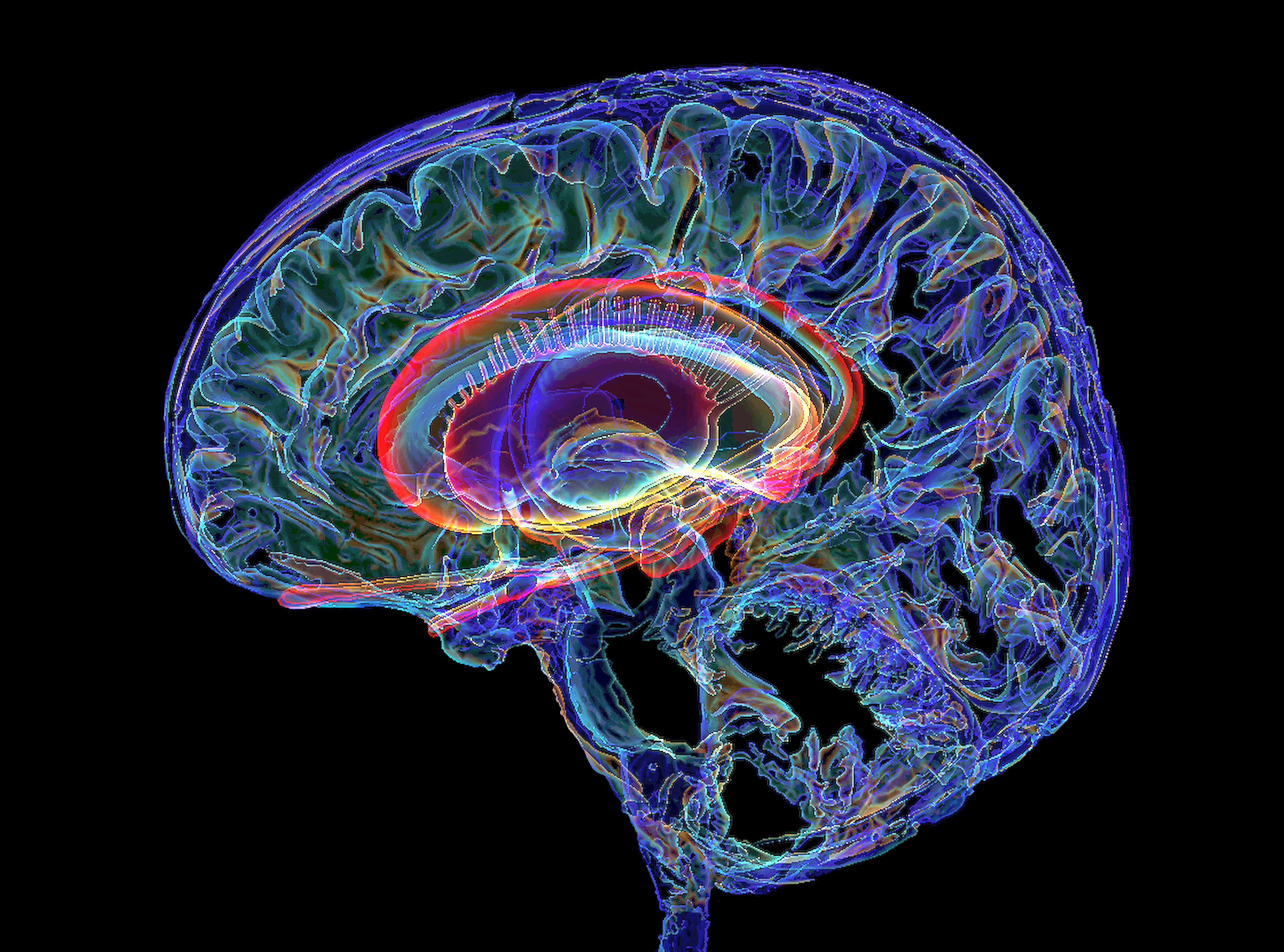

The root of these symptoms lie in how trauma shapes changes in the brain in the weeks and months after a frightening event. The brain's fear center — the amygdala — becomes hyperactive, constantly signaling danger, while the brain regions responsible for contextualizing memories and managing emotional responses become less active and less able to counterbalance those fear signals. Traditional therapies, such as antidepressant medications and trauma-focused psychotherapies, help only a fraction of patients and can take months to be effective.

"For many people with PTSD, they simply aren't enough, " Averill told Live Science.

Consequently, Averill is one of a group of researchers who are exploring a new potential avenue for treating PTSD: psychedelics. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, using MDMA or psilocybin, may act on the brain systems disrupted in PTSD, rather than simply treating the symptoms.

The early findings have been positive: A recent clinical trial showed that 67% of patients who received MDMA-assisted therapy no longer met PTSD criteria after treatment, compared with 32% in the placebo group, and clinical trials investigating psilocybin's potential to treat the condition are showing promise.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Averill is currently leading a pioneering Texas state-funded clinical trial investigating psilocybin for veterans with PTSD and has seen how quickly the drugs can act.

"There's potential for people to feel that the needle has moved in hours," Averill said. "And that is just quite literally lifesaving."

How trauma changes the brain

PTSD shares symptoms with depression and anxiety. Yet it is characterized by a response to a single trauma or set of traumatic events. Such experiences spark fear and often challenge an individual's core beliefs that the world is a just, safe and predictable place. People with PTSD can feel helpless and without agency.

It's normal for people who have endured traumatic events to experience these symptoms for a short time, and for most people, they resolve within a week or two, clinical psychologist Gregory Fonzo, a co-director of the Charmaine and Gordon McGill Center for Psychedelic Research and Therapy at the University of Texas at Austin's Dell Medical School, told Live Science. But a subset of people get stuck.

"PTSD is essentially a disorder of nonrecovery," Fonzo said.

During the instigating event, trauma activates the brain's fear alarm system, including the amygdala, and signals a rapid release of stress hormones and neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine (noradrenaline). The higher levels of norepinephrine increase arousal and the physiological “fight or flight” response. The interaction of norepinephrine and corticotropin-releasing hormone modulates increases activity between the amygdala and hippocampus, reinforcing the synaptic connections that help store fear and vivid details of the event.

For the majority of people who recover quickly, this powerful fear response is successfully extinguished. The prefrontal cortex, the brain's regulatory control system, and the hippocampus, the brain's center for memory, exert top-down control and file the event as a past memory and no longer dangerous, which restores normal signaling in the amygdala.

For people who develop PTSD, however, the trauma creates more persistent changes in the brain, Dr. Jerrold Rosenbaum, a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Neuroscience of Psychedelics at Massachusetts General Hospital, told Live Science.

In PTSD, the amygdala remains stuck in an overactive state, causing symptoms like hyperarousal, irritability and being easily startled. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex, which normally calms those alarms, becomes underactive, leaving the amygdala's overreactive fear response unchecked.

Neuroimaging has shown that PTSD is associated with a reduced volume of the hippocampus, which is the brain region that processes the context — the where, when and circumstances — of an event. In normal circumstances the hippocampus can discriminate between real and perceived danger. For example, it will categorize the sound of a car backfiring in an everyday environment differently than the blast of gunshot, which occurred specifically in a war zone. But a diminished hippocampus could make it harder for patients to distinguish between the two.

PTSD can definitely manifest in rigidity and entrenchment of ways of thinking about oneself and others in the world.

Brandon Weiss, Johns Hopkins Medical Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research

There's also evidence that PTSD is associated with changes in the connectivity of the default mode network (DMN), a set of interconnected brain regions that are highly active when a person is resting, their mind is wandering, or they are engaged in thinking about themselves or their memories rather than the outside world. Researchers hypothesize that heightened connectivity within the DMN is a neurobiological abnormality that pushes the system into overdrive, potentially leading to rumination or the involuntary re-experiencing of negative events (or flashbacks), which are characteristic symptoms of PTSD. In PTSD, the DMN also appears to be abnormally disconnected from the executive control regions and simultaneously abnormally connected with lower-level emotional systems, such as the amygdala. Scientists believe this increased coupling may drive intense, automatic emotions such as shame and guilt.

In a healthy brain, the prefrontal cortex can evaluate and change upsetting thoughts, but PTSD compromises this ability. PTSD is also associated with reduced levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a signaling protein that is critical for neural plasticity — the formation of new synapses and the strengthening or pruning of existing neural connections. The deficit in BDNF effectively "locks" the trauma response in place and can prevent the brain from integrating new, non-fearful thinking, scientists theorize.

The result is a system trapped in fearful thinking and the past.

"PTSD can definitely manifest in rigidity and entrenchment of ways of thinking about oneself and others in the world," Brandon Weiss, a psychologist at the Johns Hopkins Medical Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, told Live Science.

Treatment challenges

Physicians have used trauma-focused psychotherapy, such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT) and prolonged exposure (PE), to treat PTSD. In CPT, therapists guide patients to examine and change distorted thinking, such as the belief that they are to blame for events outside of their control. PE focuses on teaching the patient to reduce their fear by gradually confronting the traumatic memories in a controlled environment.

But these treatments are difficult for people to go through because they have to face the stuff that is really bothering them, Fonzo said. "So a lot of people drop out before they finish the treatment."

Access to specialized, trauma-focused therapists can be challenging, and not everyone benefits from such treatments, Fonzo said. Other treatment options include SSRIs, like sertraline (Zoloft) or paroxetine (Paxel), but only 20% to 30% of patients experience a remission on these drugs.

Most importantly, many patients feel like the medication hasn't addressed the root cause of their trauma, Rosenbaum said.

Creating a safe space to process trauma

For Jennifer Mitchell, a neuroscientist and the associate chief of staff for research and development at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, it was imperative to find effective treatments for military veterans suffering from PTSD.

"I see how debilitating it is for individuals that have served and have experienced combat," Mitchell told Live Science. "And we absolutely owe them to come up with better treatments."

Nearly a decade ago, Mitchell and her colleagues began to investigate whether MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), commonly known as ecstasy or molly, could treat PTSD when used in conjunction with psychotherapy. In 2023, the team published their findings on a diverse group of 104 participants with PTSD from the general population, 80% of whom had a history of contemplating suicide. By the end of the study, 71% of the participants who'd received MDMA no longer met the criteria for PTSD, and another 15% still had symptoms but had what the researchers termed a "clinically meaningful benefit."

MDMA's effectiveness hinges partly on its ability to act as a neuroplastogen — a compound that harnesses the brain's ability to form new connections and strengthen and reorganize existing connections. In the past few years, scientists have begun to explore the potential for another neuroplastogen to treat PTSD: psilocybin.

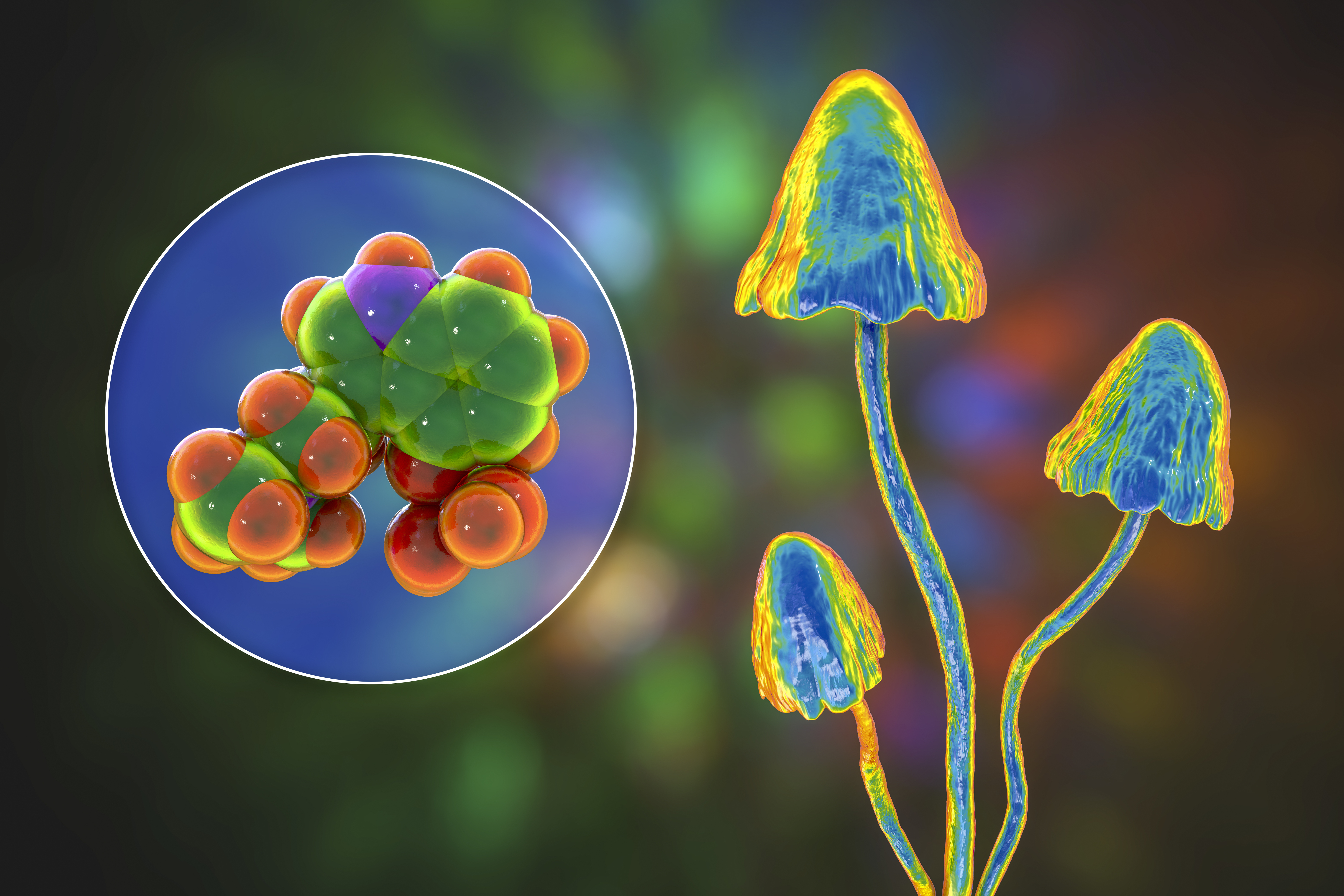

Clinical trials have found psilocybin, the main psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms, to be a promising therapy for treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, and studies conducted on animals have pointed to its potential for treating PTSD.

A study on mature adult mice demonstrated that MDMA temporarily reopens a critical period for where the brain is sensitive to learning that social behaviors are beneficial by inducing structural and functional changes in the brain’s reward circuits. Specifically the drug makes the nucleus accumbens reward circuitry more sensitive to the social hormone oxytocin. This enhanced sensitivity allows the adult brain to re-encode social cues as intrinsically rewarding and safe, facilitating the re-learning of trust and attachment for up to two weeks after a single dose, the researcher theorize.

Mitchell has witnessed similar responses in humans and hypothesizes that the drug creates a neurobiological state in which patients can form a strong, trusting bond with a therapist. "There's a therapeutic window where people feel renewed energy, they don't feel so stuck, and they can actually work on the psychological side of their issues," Mitchell said.

Simultaneously, functional neuroimaging data points to MDMA's impacts on the fear circuitry of the brain. The drug decreases activity in the amygdala while increasing activity in the prefrontal cortex. MDMA also restores normal levels of BDNF in the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, theoretically leading to the formation of new synapses and structural changes that enable greater plasticity in these regions.

Researchers hypothesize that the dampening of the fear response, the enhancement of the prefrontal cortex's regulatory role, and the restoration of flexibility in key brain regions set the scene for patients to revisit and reprocess memories without being overwhelmed by fear. By entering therapy with this more regulated perspective, recovery can happen quickly.

"By the end of a treatment session, you can see that something has shifted. The subject will be holding themselves differently and look hopeful," Mitchell said. "I've been doing this type of research for 35 years, and it is the most remarkable thing that I've seen."

Once the patients have analyzed and processed their trauma, they are less likely to slip back into their PTSD symptoms after MDMA, Mitchell said. The researchers collected data on the patients in increments over the two years after their treatment ended, and the positive benefits appear to be durable, Mitchell said.

Breaking free

When a single dose of psilocybin was injected into chronically stressed mice that had developed learned helplessness and avoidance behaviors, for example, researchers could see immediate and enduring structural changes in the rodents' brains. The rapid increase in dendritic spines — the tiny protrusions that form synapses, the connections between brain cells —suggests that psilocybin may directly reverse the loss of neuronal connections observed in the frontal cortex of rodents subjected to chronic stress, the authors suggest. And the changes could prepare the brain for fear extinction and emotional processing —key elements of overcoming trauma.

Consequently, several trials are underway to investigate psilocybin as a treatment option for PTSD. In August 2025, biotechnology company Compass Pathways published its findings on a trial designed to test the safety of psilocybin for PTSD. The small safety study wasn't designed to measure effectiveness. Nevertheless, participants seemed to show an immediate reduction in PTSD symptoms after a single 25-milligram dose of the company's synthetic psilocybin. Clinicians reported the improvements had endured when tested 12 weeks later.

In the study Averill is leading, clinicians started dosing seven participants who had experienced PTSD symptoms for an average of 19 years at the start of the trial in February. The early findings "have been incredible," Averill said during a panel discussion at the Psychedelic Science conference in Denver in June 2025.

Within a few hours of the first dose of psilocybin, every single veteran reported positive changes in their beliefs and perceptions. After the treatment effects subsided, participants underwent therapy and said the drug enabled them to reevaluate their original traumatic experiences from a nonjudgmental perspective, without the shame and guilt, Averill said.

So how does psilocybin bring about these changes?

Studies in mice have demonstrated that, in a similar vein to MDMA, psilocybin helps brain cells grow new dendritic spines. These new branches appear in the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, the key regions responsible for learning, planning and memory.

But brain scans from people have shown that psilocybin simultaneously disrupts and desynchronizes, or dissolves, connectivity within the DMN for three weeks. Scientists hypothesize that this desynchronization of the brain system involved in self-referential processing results in a mind that is less constrained, more flexible and less consumed by self-reproach. They propose that the disruption of rigid cognitive patterns and negative thought loops may promote psychological flexibility and self-compassion.

"It has been surprising to see these maladaptive beliefs shift when I'd learned that change would only come about through longer term talk therapy," Weiss said.

Dissolving rigid thinking can open up the mind to new possibilities, including the idea that the patient wasn't responsible for the original trauma, Weiss said. Weiss is currently carrying out a clinical trial examining the effect of psilocybin therapy on the cognitive beliefs related to PTSD and is witnessing participants' experiences of the treatment.

"Many are endorsing less guilt and are able to let go of the sense that they were to blame for this happening," he said.

Proceeding cautiously, with haste

When Fonzo first reviewed the data on psychedelics as a treatment option in mental health, he was excited by what he found. But he pointed out that there haven't yet been any large, controlled studies evaluating psilocybin for PTSD. The research is still in its early stages with small pilot studies or clinical trials still assessing the safety of the drug. "There needs to be a sober perspective on what the evidence does, and does not show," Fonzo said, "because these treatments aren't necessarily going to be suitable for everyone."

Fonzo believes the answer lies in the expansion of funding for clinical trials, but research in psychedelics still faces steep hurdles. Both MDMA and psilocybin are listed as Schedule I substances in the U.S. — a federal classification reserved for drugs considered to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use. That label makes studying them a bureaucratic nightmare, as researchers must navigate complex regulatory approvals and secure special licenses just to handle the compounds.

On top of that, every trial demands careful screening to find participants who meet the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Also, due to the profound and unmistakable psychoactive effects of psychedelics, in trials, it can be hard to hide who is and isn't getting the drug and thus create a robust placebo group.

Despite these challenges, new clinical trials are underway to explore variations in dosage, psychotherapy pairing and long-term outcomes. Weiss and his colleagues are investigating administering combinations of MDMA and psilocybin — so-called psychedelic stacking — and comparing the effectiveness of each treatment separately. "We're still learning about what is the most efficient and rapid-acting approach to helping people," Weiss said.

For veterans who are experiencing suicidal thoughts as part of their PTSD, finding interventions that spur rapid change could be key, Weiss said. Despite the compelling findings, the regulatory approval of psychedelic treatments for PTSD is moving slowly. In August 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration declined to approve MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, citing concerns over the study design and blinding procedures. Mitchell has been frustrated about the decision not to approve the treatment with guardrails, or for a subset of people who really need it.

"My own brain gets cranky when I hear people not consider PTSD a life-threatening condition — because it is," Mitchell said. In the United States in 2024, an average of 17 veterans died each day by suicide.

"That's why speed matters. We can't wait months for treatments that barely work," Mitchell said.

Averill has witnessed PTSD patients liberated by psychedelic therapy, but she cautioned that the psychedelic experience is not a "silver bullet" but rather one that opens the doors to healing. One veteran in the clinical trial she'd been leading described feeling like he'd been locked in a cage and said every movement felt painful. The psilocybin removed the cage, and he was able to revisit his traumatic experiences.

Averill's goal is to continue exploring how psychedelic-assisted therapy can help PTSD sufferers move beyond merely tolerating their existence. "We want to help people move forward and build lives they really want to be living," Averill said.

Jane Palmer is a Colorado-based journalist who is contributing to Live Science with a focus on biodiversity conservation, neuroscience and mental health. She has written about science for many outlets including Nature, Science, Eos Magazine, Al Jazeera, BBC Earth, BBC Future, Mosaic Science and Proto Magazine. Before becoming a journalist, Palmer was a scientist, and she earned a bachelor's degree in cognitive science and a doctorate in computational molecular modeling from the University of Sheffield in England. She enjoys reading and being outside in nature whenever possible, preferably climbing rocks.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus