'The sun is slowly waking up': NASA warns that there may be more extreme space weather for decades to come

A new NASA study suggests that solar activity will remain high or rise further in the coming decades, contradicting previous assumptions that the sun was quieting down — and scientists "don't completely understand" why.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NASA scientists are warning that the sun may be "waking up" from a brief period of relative inactivity, contradicting past assumptions about our home star. If true, this could mean that decades of potentially dangerous space weather are in store.

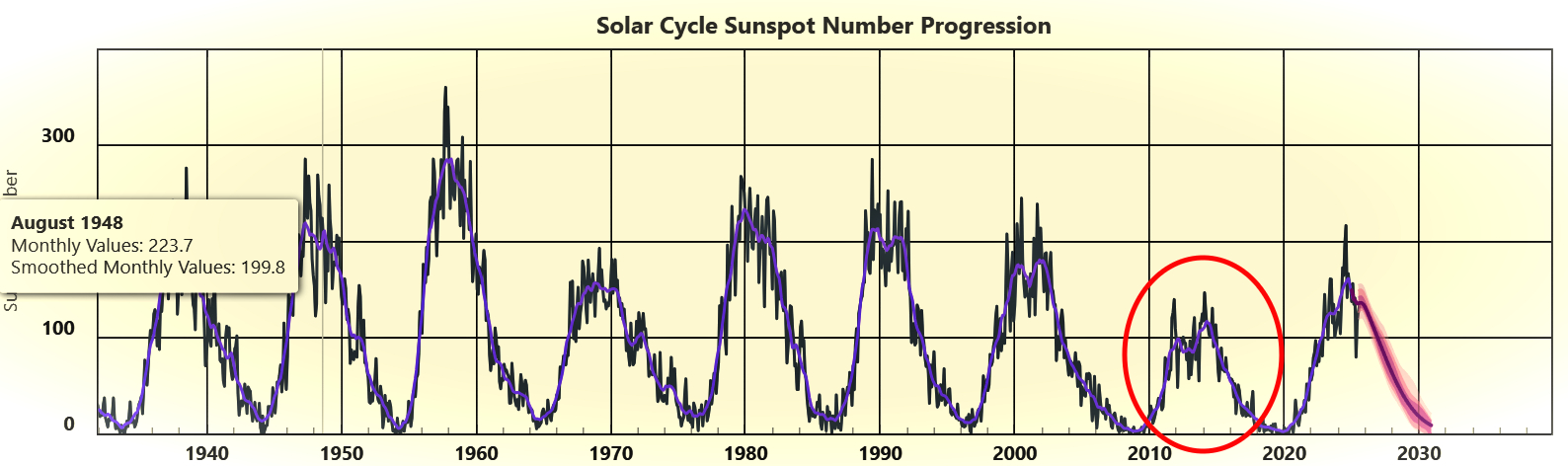

The sun follows a roughly 11-year cycle of solar activity that begins with a prolonged quiet period, known as solar minimum, and builds toward an explosive peak, known as solar maximum — when our home star frequently spits out powerful solar storms at us. This pattern is known as the "sunspot cycle," because the number of dark patches on the sun's surface rises and falls with solar activity. The sunspot cycle is, in turn, governed by a longer 22-year cycle, known as the Hale Cycle — during which the sun's magnetic field entirely flips and then reverses back again.

But in addition to the sunspot and Hale cycles, the sun also experiences long-term fluctuations in solar activity that can span multiple decades and are much harder to predict or explain. Examples include periods between 1645 to 1715, known as the Maunder Minimum, and between 1790 and 1830, known as the Dalton Minimum, when solar activity was generally much lower throughout successive sunspot cycles.

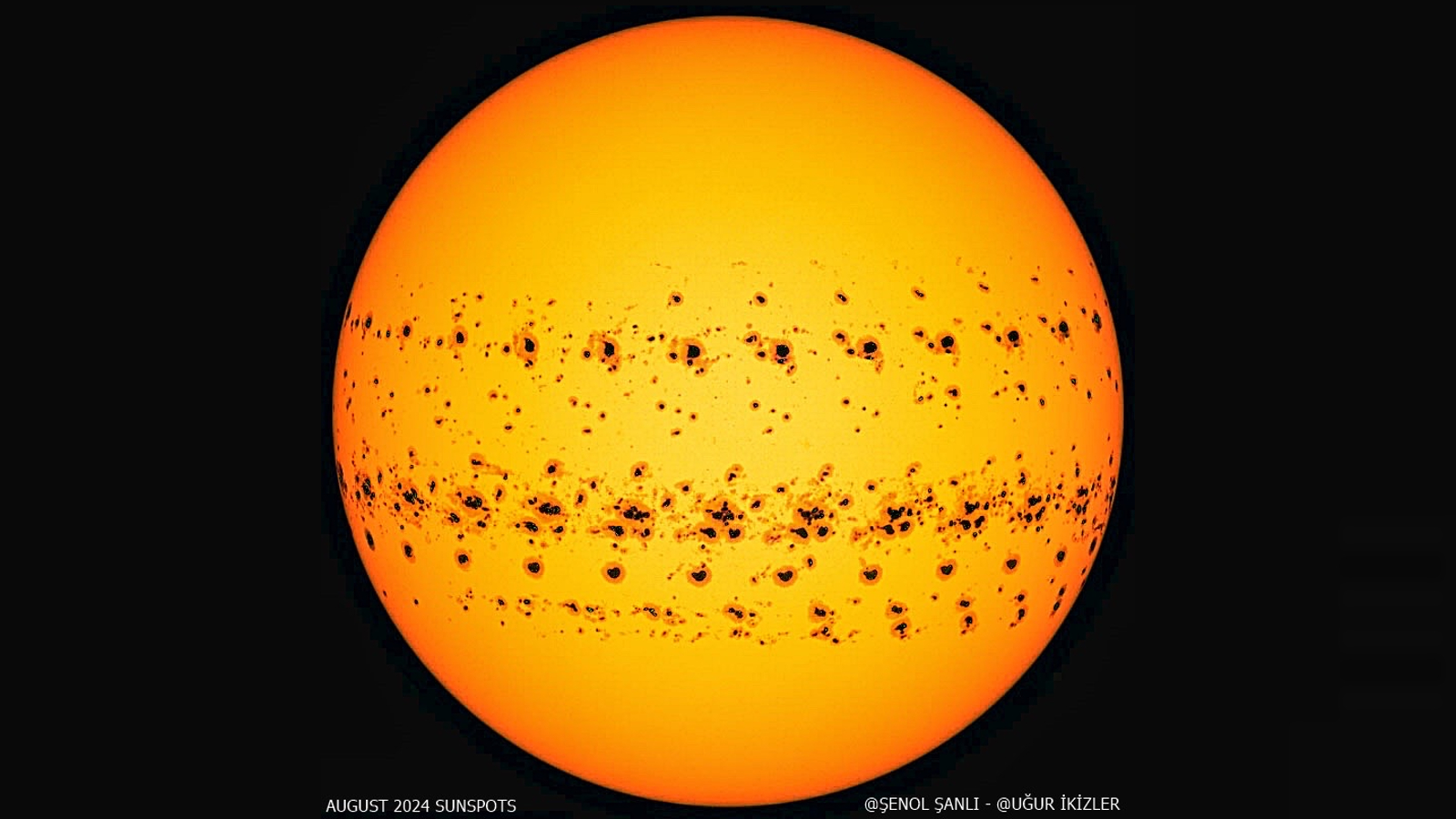

Back in the early 2000s, downward trending solar activity led some scientists to believe that we were possibly entering a new "deep solar minimum." This theory gained traction after the last solar maximum, between 2013 and 2014, which was much weaker than previous cycles. However, the current sunspot cycle, which has just peaked, has massively upended this theory.

In a new study, published Sept. 8 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers analyzed multiple metrics of solar activity, including solar wind, magnetic field strength and sunspot numbers, and found that they have been on an upward trend since around 2008, and could rise further over future cycles, suggesting that the deep solar minimum theory is well and truly dead.

Related: 10 supercharged solar storms that blew us away in 2024

"All signs were pointing to the sun going into a prolonged phase of low activity," study lead author Jamie Jasinski, a plasma physicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a NASA statement. "So it was a surprise to see that trend reversed. The sun is slowly waking up."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

We are currently coming towards the end of the sun's most recent solar maximum, which officially began in early 2024, and it has not played out as expected.

When the current sunspot cycle began in late 2019, experts from the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) — which includes scientists from NASA and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) — predicted that solar maximum would most likely begin sometime in 2025 and be comparable to the previous weaker cycle.

However, as the current cycle progressed, it quickly became clear that this was not the case and that solar maximum would arrive sooner and be much more active than initially predicted. SWPC scientists later acknowledged their mistake, issuing their first-ever updated forecast, which came just in time for solar maximum's arrival.

Since then, the sun has reached its highest number of sunspots in more than 20 years and spat out a record number of powerful X-class flares — the most powerful type of explosion the sun is capable of producing.

During the current maximum, Earth has also been hit by several major geomagnetic storms, or disturbances to the planet's magnetic field. The most noteworthy was an "extreme" event in May 2024, which triggered some of the most vibrant aurora displays in centuries and caused over $500 million in damages.

Now, the new study warns that what we have witnessed over the past few years will likely become the "status quo" over the next few decades. This could be especially problematic because humanity has become much more reliant on technologies that are prone to interference from space weather, such as power grids, GPS-controlled machinery and Earth-orbiting satellites, which can be knocked out of the sky by solar storms.

It is currently unclear why the sun experienced a blip in solar activity over the last few decades or what may be driving its current resurgence: "The longer-term trends are a lot less predictable and are something we don't completely understand yet," Jasinski said.

Another study from earlier this year proposed that the recent surge in activity could be part of a lesser-known and understudied 100-year solar cycle, known as the Centennial Gleissberg Cycle. However, the newest study does not mention this at all.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus