Controversial startup's plan to 'sell sunlight' using giant mirrors in space would be 'catastrophic' and 'horrifying,' astronomers warn

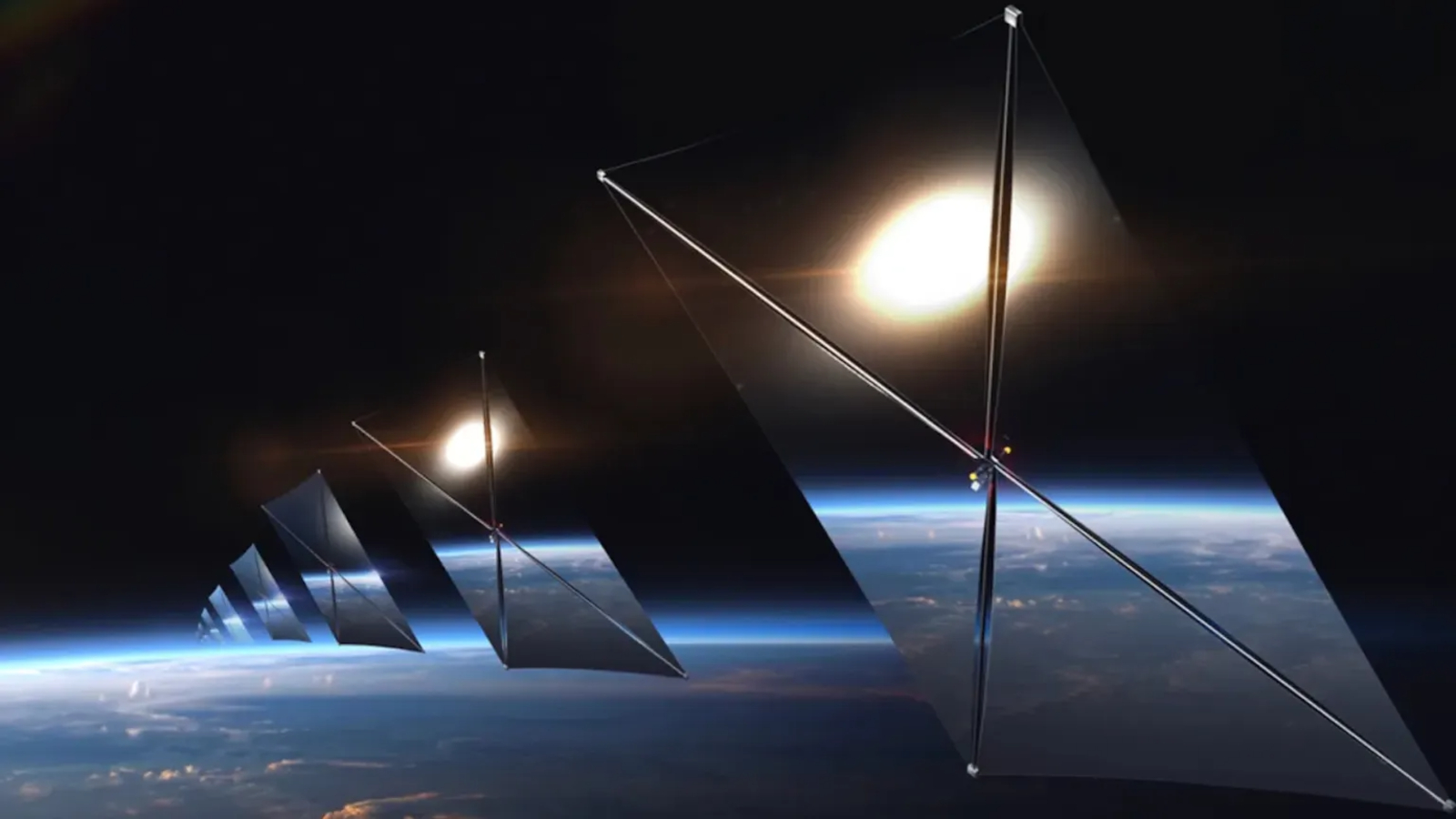

California-based startup Reflect Orbital aims to build a swarm of 4,000 giant mirrors in low Earth orbit to "sell sunlight" to customers at night. Experts warn that the mirrors could mess with telescopes, blind stargazers and impact the environment.

A California-based startup's controversial plan to put 4,000 tennis-court-sized mirrors in orbit around Earth is "catastrophic" and "horrifying," astronomers warn.

Reflect Orbital, which was founded in 2021, has recently taken the first step in a scheme to sell sunlight at night by bouncing solar rays off giant "reflectors" that can redirect the vital resource almost anywhere on our planet. By doing this, the company aims to extend daylight hours in specific locations, thus allowing paying customers to generate solar power, grow crops and replace urban lighting.

But experts say it is a wildly impractical plan that should never get off the ground. What's more, the resulting light pollution could devastate ground-based astronomy, distract aircraft pilots and even blind stargazers.

As its first step, Reflect Orbital recently submitted an application to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to launch its first test satellite, EARENDIL-1, in early 2026. If this application is granted and the initial tests are successful, the startup envisions launching as many as 4,000 similar satellites by 2030, company representatives recently told Live Science's sister site Space.com.

Once in low Earth orbit (LEO), EARENDIL-1 would unfurl a square reflector up to 59 feet (18 meters) across, giving it a surface area of around 3,500 square feet (325 square meters). This would allow the mirror to illuminate a single patch of Earth's surface up to 3 miles (5 kilometers) across at a time. From the ground, the light within one of these patches would be up to four times brighter than the full moon, the company representatives said.

However, future reflectors in the planned constellation could have mirrors up to 177 feet (54 m) across, which would likely create larger and more intense bright spots.

Reflect Orbital said it can minimize the effects of its light pollution by rotating the mirrors away from Earth when they're not in use. "Our service is highly localized," company representatives told Space.com. "Each reflection covers a defined area for a finite period of time rather than providing continuous or widespread illumination."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, these reassurances have done little to put scientists at ease.

"A terrible idea"

The reflectors would orbit Earth in a sun-synchronous orbit, which would cause them to circle Earth from pole to pole, perpendicular to the planet's spin. They would be positioned to constantly align over the day-night divide on our planet, essentially allowing the mirrors to bounce sun's rays from the daylight side onto locations that are dark. In theory, this would illuminate areas just after sunset or before dawn.

But while the basic physics behind this idea is solid, experts say it is much easier said than done — and they are skeptical that the company could pull it off.

Their plan "is flawed from the outset, technically speaking," Fionagh Thomson, a researcher at Durham University in England who specializes in space ethics, told Live Science in an email. "It is highly unlikely to come to fruition due to the complexity of the engineering involved, and trying to operate through busy orbits such as LEO."

In fact, this idea has been tried — and subsequently abandoned — before. In 1993 and 1999, Russia attempted to launch two similar reflectors, dubbed the Znamya satellites, but canceled the program after struggling to control the satellites, which both quickly burned up in the atmosphere. (No other reflectors have been launched since.)

Researchers writing in The Conversation and Big Think have also questioned whether the mirrors are capable of delivering one of the company's future flagship services: generating solar power.

In theory, the mirrors could be used to shine light on giant solar farms on the planet's surface, thereby extending the amount of time they can create electricity. However, the resulting light would be thousands of times weaker than the midday sun, meaning the illuminated panels would generate a tiny fraction of their normal energy. Moreover, a single mirror could focus light onto the same spot for a maximum of only four minutes at a time, the researchers predict.

Even if the mirrors could collectively generate enough energy, it would be "eye-wateringly expensive" compared with other forms of renewable energy, Thomson said.

All in all, "this is a terrible idea," Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina in Canada, told Live Science in an email. However, there is still a decent chance that the EARENDIL-1 mission will be approved by the FCC, she speculated.

Blinded by the light

A single mirror is unlikely to have a major impact on the night sky. But if Reflect Orbital's proposed constellation is realized, astronomers say it will be increasingly hard to study the stars beyond the glare of thousands of "new stars" zooming across the night sky.

Robert Massey, deputy executive director at the U.K.'s Royal Astronomical Society, told Space.com that the astronomical community was "seriously concerned about the development, its impact and the precedent it sets."

While other spacecraft, such as SpaceX's Starlink satellites, accidentally reflect light toward Earth's surface, astronomers are particularly worried by the deliberate generation of light pollution proposed by Reflect Orbital.

"The central goal of this project is to light up the sky and extend daylight, and obviously, from an astronomical perspective, that's pretty catastrophic," Massey said.

For unlucky stargazers who ended up in one of the mirrors' bright spots, it would also be almost impossible to see any other stars in the night sky, Lawler said. Past research into this concept has also shown that staring directly at the reflectors through a telescope or binoculars could cause eye damage, she added.

Given that a mirror could be suddenly rotated or repositioned at any location on Earth without warning, there is no guaranteed way of avoiding this. And sudden flashing from a reflector's movement could also distract aircraft pilots during takeoff or landing, with potentially disastrous consequences, several experts have said.

Past research on light pollution has also shown that it can alter the behavior of a wide array of animals and plant species, as well as disrupt human sleep cycles.

"One tiny company in California can, with a few million dollars and the approval of a single U.S. federal agency, change the night sky for everyone in the world," Lawler said. "It's horrifying."

Additional issues

While astronomers are mostly concerned about the light pollution and the invisible radio pollution these mirrors will likely create, the planned swarm could prove dangerous in other ways.

For example, the mirrors' large size makes them more likely to be hit by micrometeorites or the rapidly multiplying bits of space junk that encircle our planet, Lawler said. This could leave the reflectors "riddled with holes," which would make them harder to control, she added.

If operators lost control of a mirror, it could end up spinning out, similar to NASA's Advanced Composite Solar Sail System, which began tumbling end over end after being deployed in August 2024. If this happened, the mirrors would uncontrollably flash across the night sky.

Additionally, the number of planned satellites across the globe is already higher than the number of spacecraft that experts predict can safely operate in LEO. And the new reflectors would eventually fall back to Earth at the end of their operational lifespan, which could lead to issues such as atmospheric metal pollution.

As for the potential wildlife impacts of the project, Reflect Orbital has committed to carrying out an environmental risk assessment, but only after EARENDIL-1 is launched, according to Space.com.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus