Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

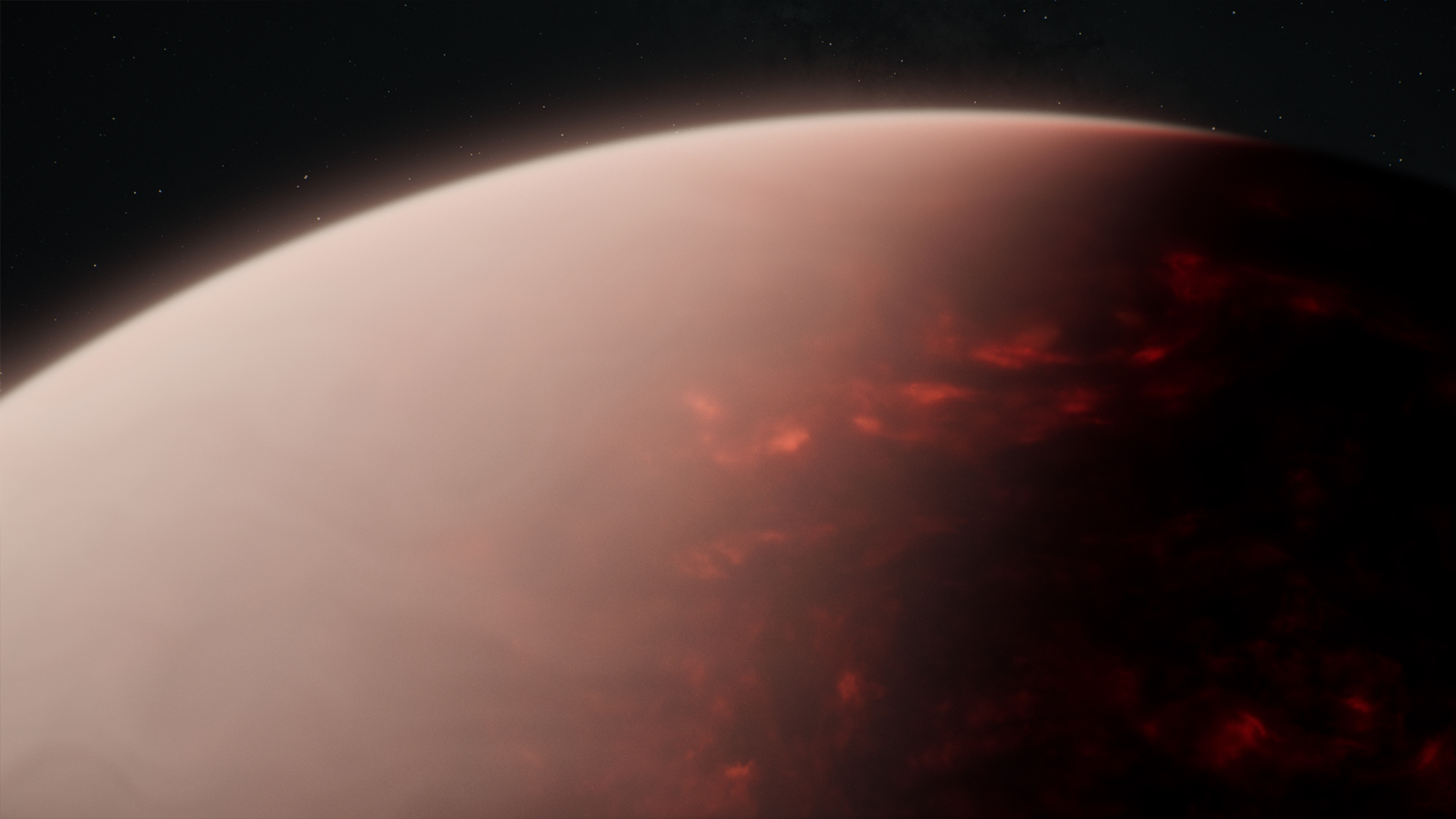

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has spotted a distant exoplanet that should be impossible. The ultrahot super-Earth, named TOI-561 b, is surrounded by a thick atmosphere of hot gas that blankets a planet covered by a broiling magma ocean.

Astronomers have been surprised by several of the hell planet's features, which don't match what we've found elsewhere in the universe. The discovery could reshape what we know about the types of planets that can form and evolve.

"What's really exciting is that this new data set is opening up even more questions than it's answering," study lead author Johanna Teske, staff scientist at Carnegie Science Earth and Planets Laboratory in Washington D.C. said in a statement from NASA.

Hot, close to the sun, and tidally locked

TOI-561 b is located around 280 light-years from Earth in the constellation Sextans, and it has a radius about 1.4 times that of our own planet. It circles its sun, which is slightly smaller and cooler than our own, every 11 hours, according to the statement. That puts it in a rare class of objects known as ultra-short period exoplanets, according to NASA.

The planet orbits incredibly closely to its parent star — just 1/40th the distance between Mercury and the sun, the statement noted. That means it is "tidally locked," or keeps one side of the planet perpetually facing the star — much like Earth's moon is tidally locked with our planet. Such tidally locked planets have a permanent dayside and permanent nightside.

Too light, too cool, too atmospheric

The distant hell planet is puzzling to researchers in many ways.

For one, it has an unusually low density. That is likely because it formed very differently than the planets we are most familiar with.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"TOI-561 b is distinct among ultra-short period planets in that it orbits a very old (twice as old as the Sun), iron-poor star in a region of the Milky Way known as the thick disk," Teske said. "It must have formed in a very different chemical environment from the planets in our own solar system."

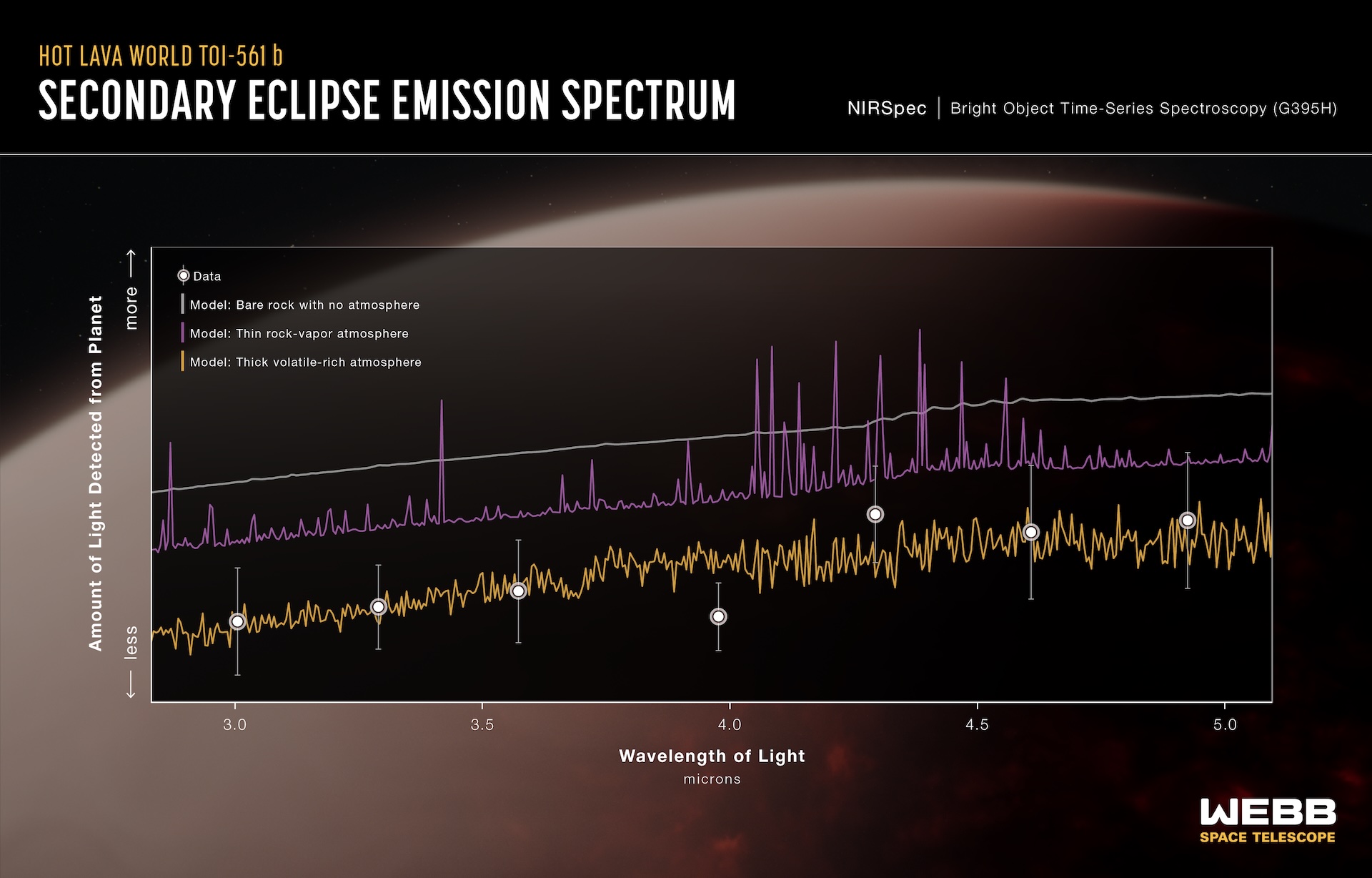

But the bigger surprise came when researchers took a look using JWST. The telescope's NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) instrument revealed the planet's dayside temperature by measuring how much the light from the planet dimmed as it moved behind its host star. Based on the type of star it circles and its distance, the temperature should be up to 4,900 degrees Fahrenheit (2,700 degrees Celsius) if the planet were bare rock. Yet TOI-561 b measured just 3,200 F (1,800 C).

The team tested, then discarded, a number of explanations for the anomalously cool temperature. None could explain the discrepancy except for one: that the planet has a thick atmosphere.

That defied their expectations. Planets that have been orbiting so closely to their star for so long are expected not to have an atmosphere, because eons of radiation from the parent star should have blasted it away. So how did TOI-601 b hold on to its atmosphere?

The atmosphere must contain more volatile chemicals than Earth's atmosphere does, study co-author Tim Lichtenberg, an astronomer at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, said in the statement.

That would confer strong winds that carry heat from the planet's dayside to its permanent nightside. An atmosphere would also provide water vapor that could soak up some near-infrared light before it could pass through the atmosphere and into JWST's instruments. And bright clouds filled with silicates, a key ingredient in rocks on Earth, could also reflect starlight, study co-author Anjali Piette, an astronomer at the University of Birmingham, U.K., said in the statement.

"We really need a thick volatile-rich atmosphere to explain all the observations," Piette said.

The researchers published their findings Dec. 11 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

One of JWST's core missions is finding and characterizing atmospheres around exoplanets, because (as far as we know) an atmosphere is a prerequisite for life. While it's extremely unlikely that this broiling hell planet is habitable in any sense, studying its atmosphere with JWST could help scientists better understand how planetary atmospheres form, and how the powerful telescope could be best used to find evidence of alien life.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus