New discoveries at Hadrian's Wall are changing the picture of what life was like on the border of the Roman Empire

The British northern frontier was the edge of the Roman world — and a place of violence, boredom and opportunity, experts told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two millennia ago, the Roman Empire reached the limits of its power in Britain. The island marked the northernmost border of the Roman Empire and the point at which the ancient superpower's expansion came to a halt.

The Romans launched several invasions and kept 10% of the entire army in the province but failed to conquer the whole island. Instead, a militarized frontier divided the island in two — marked by the 73-mile-long (118 kilometers) Hadrian's Wall, which was the border for nearly 300 years.

One key source of information we've gleaned about this borderland is a historic fort called Vindolanda, which was built by the Romans in what is now Northumberland in England and once housed units of soldiers from across the empire. The site holds layers of history from the Roman era as it was demolished and rebuilt nine times by its occupants.

Article continues belowWhile Vindolanda has been studied for decades, new discoveries are changing the picture of what life was like on the edge of the empire. The Roman frontier was far from a forbidding, "Game of Thrones"-like outpost in the middle of nowhere, defended only by men. Instead, clues point to a diverse community that was a demographic snapshot of the entire empire. And the site is shining a light on some of the most understudied groups in Roman society.

The northern frontier

The Romans successfully invaded Britain in A.D. 43 and within a few decades had pushed as far north as Scotland. But after battles with Indigenous groups like the Caledonians, Rome pulled back to northern England. To secure the empire's position, in A.D. 122 Emperor Hadrian constructed a vast wall that spanned from what is now Newcastle in the east to Carlisle near the western coast. Hadrian's Wall, as it is now known, was dotted with forts, spikes, ditches and earthworks, and was guarded by auxiliaries — troops who were not Roman citizens but came from across the empire. (This changed in A.D. 212, when most free people in the empire were granted citizenship.)

These auxiliaries "basically go from being a conquered group living in a conquered province to being part of the very war machine that then conquers more places," Elizabeth Greene, Canada research chair in Roman archaeology at Western University in Ontario, told Live Science.

But the wall was never intended to demarcate the end of Roman influence.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Hadrian [essentially] says, 'OK, we're going to stop here, the North is not conquered, but we control it from this line,'" Andrew Gardner, a professor of Roman archaeology at University College London, told Live Science.

While the idea of a vast wall spanning the breadth of northern Britain sounds forbidding and desolate, it was anything but, experts told Live Science.

It wasn't "the 'Game of Thrones' model of the frontier, with a great cranking elevator leading you to floor 5 million and then you just pee off the edge of the world," Marta Alberti-Dunn, deputy director of excavations at the Vindolanda Trust, told Live Science. "No, it's a very busy in-and-out space."

Military communities

Early archaeologists in the 19th century believed auxiliaries manned the frontier alone, "living like monks in fortified enclosures," Gardner told Live Science. But research has since revealed they had families with them, even before Hadrian's Wall cemented the frontier.

"Soldiers were legally not allowed to marry," which led early researchers to discount the notion of military families springing up near the frontier, Greene said. "Now does that stop anyone from having a relationship with a woman and having children? It does not. And we have a whole body of evidence that tells us that."

Excavations at Vindolanda and other sites revealed that the military forts were nestled alongside "extramural" settlements, meaning civilian settlements outside the walls. But recent research shows that the military community was even more closely intertwined, with families of officers, and even low-ranking soldiers, likely living and working inside the forts, Greene said. "We absolutely have this open community."

A treasure trove of evidence from Vindolanda has yielded unprecedented glimpses into these communities.

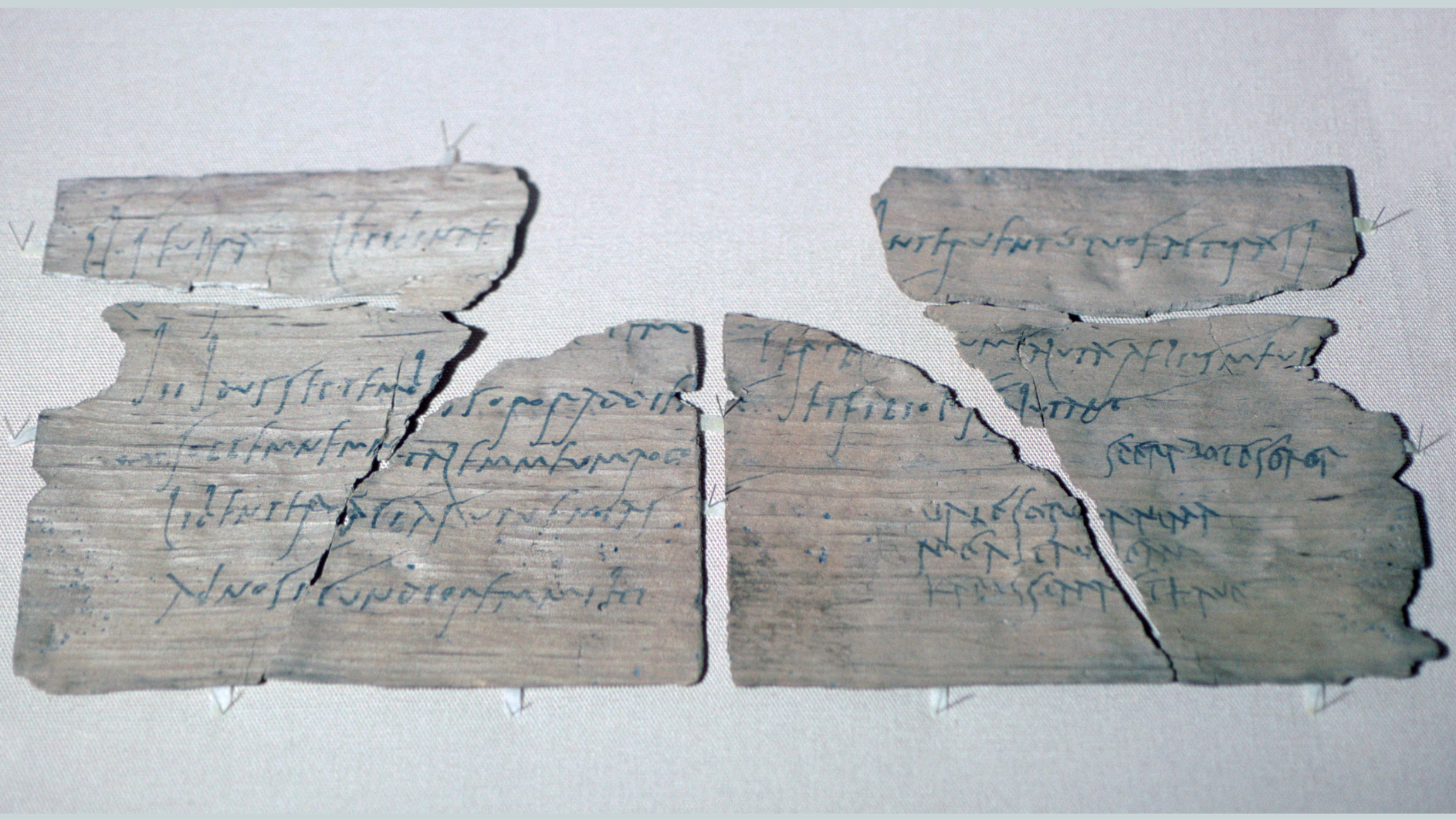

Key to modern archaeologists' understanding of life on the frontier are artifacts known as the Vindolanda tablets, Alberti-Dunn said. Around 1,700 of these postcard-size wooden tablets, scribbled on with ink, have been found at Vindolanda. They date to around A.D. 100, before Hadrian's Wall was built and when the fort sat on an important road.

One of the most famous tablets "is from Claudia Severa to Sulpicia Lepidina and is inviting Sulpicia to Claudia's birthday party," Alberti-Dunn said. "It's the earliest example of female handwriting [in Latin]."

A wealth of leather shoes abandoned at Vindolanda also reveal windows into people's lives, including their social status and even where they lived in the settlement.

"The shoes are really great because they tell us exactly who's there," Greene said, including women and children from the earliest occupation of the fort. Around 5,000 shoe parts have been unearthed at Vindolanda and a nearby fort called Magna, Greene noted, including mysteriously large shoes found earlier this year. (It's unclear if some people there had massive feet, or if the shoes were large because people were wearing multiple pairs of socks to stay warm.)

People and society

New discoveries at Vindolanda are also revealing that military settlements along the frontier were complex societies.

"So you've got these 'de facto wives' who are living probably outside in the extramural settlement. They have no status because they're not [Roman] citizens," Greene added. "But you've got elite women as well" who likely played a public role in frontier life, Greene said.

Researchers are also finding more evidence of enslaved people in the forts and settlements. "We know there were enslaved people in the military. Lots of them. But we know so little about them," Greene said.

For instance, in the past few years, archaeologists used new techniques to finally decipher a Vindolanda tablet that was previously illegible. It turned out to be a deed of sale for an enslaved person, according to a study published earlier this year. Other evidence includes the Regina Tombstone in the frontier fort Arbeia near Newcastle, which depicted an enslaved woman and featured an inscription that described her life.

"She was the slave of an individual named Barates. He was probably a soldier or merchant," Greene explained. "She's Catuvellauni, which is a British tribe. He's from across the empire in Syria, she was his slave and he married her."

Merchants also gathered around the forts, and the Vindolanda tablets chronicle discussions about money and supplies, and even show evidence that local Celtic entrepreneurs profited from the military outpost.

"These are people who serve each other's needs," Alberti-Dunn said. "The people who might reside outside the fort need the people who live inside the fort in order to make money out of them."

Diverse frontier

Auxiliaries on the frontier were recruited from across the empire — from the Netherlands, Belgium, and even Spain and Syria — and they brought diverse cultures to the northern frontier.

That meant people stationed there amalgamated beliefs. "At Vindolanda, we have a stone to De Gallia, the personification of Gaul; we have a stone to a goddess named Ahvardua, which is not known anywhere else but there," Greene said. In the empire religious syncretism — combining different religions or beliefs — was accepted, and there were syncretized deities in Vindolanda, Greene added.

These communities held Roman festivals but worshipped Roman deities such as Jupiter Optimus Maximus and Victory, alongside local Celtic deities such as Sattada.

The troops stationed at the forts may have even brought their own unique hierarchies. "The Batavians [a German tribe from what is now the Netherlands] put out that they could cross a river in full armor and not drown," Alberti-Dunn said.

These fearless, bloodthirsty assassins were notoriously hard to rule, and the Batavians addressed their commanding officer as "my king," Alberti-Dunn said. That suggests the commanding officer was Batavian nobility akin to a client king whom the Romans appointed because it was too difficult to control the Batavians otherwise, Alberti-Dunn added.

Danger and boredom

With such a large military presence, it's easy to think the frontier was dangerous. But evidence paints a mixed picture.

There are hints of tumultuous periods, such as the Romans' abandonment of the farther north Antonine Wall in Scotland just 20 years after they built it in A.D. 142, Rebecca Jones, keeper of history and archaeology at National Museums Scotland, told Live Science.

Another moment of danger came during Septimius Severus' invasion of Scotland in A.D. 208. "It's one of the bloodiest times for Britain, it's horrible for the Roman army. [There were] uncounted casualties on the Roman side, uncounted casualties on the non-Roman side," Alberti-Dunn said. "It's just a hot mess."

But for most of the Roman period, frontier life was more mundane. One tablet discusses preparing for storms, while another reveals a soldier, unprompted, sent a fellow soldier socks and underwear. Others concern gardening.

People in the settlements, meanwhile, staved off boredom by playing games and visiting bath houses.

Frontier life came with other downsides. New research detailing the excavation of a latrine revealed that many soldiers had worms, Jones noted, while research published last year revealed the widespread presence of bedbugs. "It doesn't make the whole thing particularly glamorous," Jones added.

Ongoing research into what Roman soldiers in Britain ate suggests it was a meat-heavy diet — particularly beef. "I think meat was absolutely core to the Roman military diet," Richard Madgwick, a professor of archaeological science at Cardiff University who is leading the project, told Live Science.

Archaeologists have also found evidence of imported foods, such as wine and fish oil along Hadrian's Wall, as well as North African cooking styles on the Antonine Wall, Jones noted.

The local people

Britain was populated by more than 20 different Celtic groups, such as the Iceni in the east — made famous by Boudica — and the Brigantes and Caledonians farther north. But the Romans rarely mention Britons — one Vindolanda tablet dismissively calls them Britunculi — "wretched little Brits."

Researchers are digging deeper into life in these Celtic communities. "There's a mixture of deprivation, oppression and poverty," Gardner said. "At the same time, in some situations, there's a degree of opportunity."

Yet-to-be-published research indicates Iron Age communities north of the wall saw a population drop between A.D. 200 and 400, during the later Roman Empire period of Britain, Jones said.

"That reduction of population could be for enslavement; it could be through violence and death," Jones added. "It could also be through conscription and enlistment."

The Romans set up camps north of Hadrian's Wall and maintained a military presence to some extent in the north, Gardner noted, which may have contributed to this population decline.

Growing evidence suggests that Celtic people north and south of the frontier profited from the Roman presence. For example, evidence has revealed that Roman forces were being supplied with animals bred in Highland Scotland, Madgwick noted. "Is it trading, or is it raiding? The more I look into it, the more I think there's evidence that these were being bred and raised with Romans in mind. … This was a fantastic economic opportunity."

The auxiliary units guarding the frontier even recruited British men. "This is the paradox of people's lives being shaped by … the imposition of military control, people being killed, people being enslaved," Gardner said. "But local people find ways to live still and sometimes to find opportunities. So even joining the military itself becomes an opportunity," he added.

The Romans withdrew from Britain around A.D. 410, but Vindolanda remained occupied by Christian communities — possibly the descendants of former Roman soldiers stationed there — until the ninth century.

James is Live Science’s production editor and is based near London in the U.K. Before joining Live Science, he worked on a number of magazines, including How It Works, History of War and Digital Photographer. He also previously worked in Madrid, Spain, helping to create history and science textbooks and learning resources for schools. He has a bachelor’s degree in English and History from Coventry University.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus