'It's really an extraordinary story,' historian Steven Tuck says of the Romans he tracked who survived the AD 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius

"I have found two or three rich guys, but I found a couple hundred middle class and even some desperately poor people who made it out and left records. And that shocked me."

The eerie casts of the victims of the A.D. 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius paint a desolate picture of the destruction the volcano wrought on ancient cities near modern Naples. Pompeii became a 2,000-year-old time capsule when the city was frozen underneath layers of pumice, ash and pyroclastic flows.

Over the span of two centuries, archaeologists have uncovered Pompeii and its neighbor Herculaneum bit by bit, identifying quotidian remains of Roman art, architecture and food. But less attention has been paid to the things missing from the cities — and the people who carried them as they escaped the obliterating force of Vesuvius.

Steven Tuck, a classics professor at Miami University in Ohio, has used historical and archaeological data to trace the paths of people who restarted their lives and reestablished their communities after escaping Vesuvius. He spoke with Live Science about his new book, "Escape from Pompeii: The Great Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Its Survivors" (Oxford University Press, 2025).

Editor's note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Related: Read an excerpt from Tuck's new book, "Escape from Pompeii."

Kristina Killgrove: How did you get interested in learning about the people who escaped from Pompeii?

Steven Tuck: My undergraduate advisor J. Rufus Fears is the first person that proposed this idea to me. We were standing at the site of Cumae, just north of the Bay of Naples on the acropolis looking out over the city, and he said, "Why do you think the emperor Domitian built so much at Cumae?" And we all went, "I don't know." He said, "Let me ask you another question then. What do you think happened to the people that got out from Pompeii?"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He just swept his arm dramatically gesturing at the city down below us. And it was the first time that ever occurred to me. I just started reading about it and realized nobody had written about this, partly because nobody could figure out how to find these people. It took me years to come up with a methodology to prove that people got out, and then where they went, and then to be able to ask some questions about them.

KK: That's a great story. So before you started this work, who did you think escaped, and did that change after you started doing your research?

ST: I made a lot of mistaken assumptions early on. Part of that was [thinking] this will only take me a couple years. Also, I thought I would find maybe two or three rich guys who had gotten out — who had seen the eruption, turned to their enslaved housekeeper, handed him the keys and said, "I'll be back." And legged it out of town.

Rich people are easier to find in the written record. So I thought, I'm going to find a couple rich guys. Totally messed that up. I have found two or three rich guys, but I found a couple hundred middle class and even some desperately poor people who made it out and left records. That shocked me. I had no idea that was coming.

KK: It sounds like the sequence of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius wasn't necessarily instantaneous. How quickly did the eruption happen that it gave people a chance to flee?

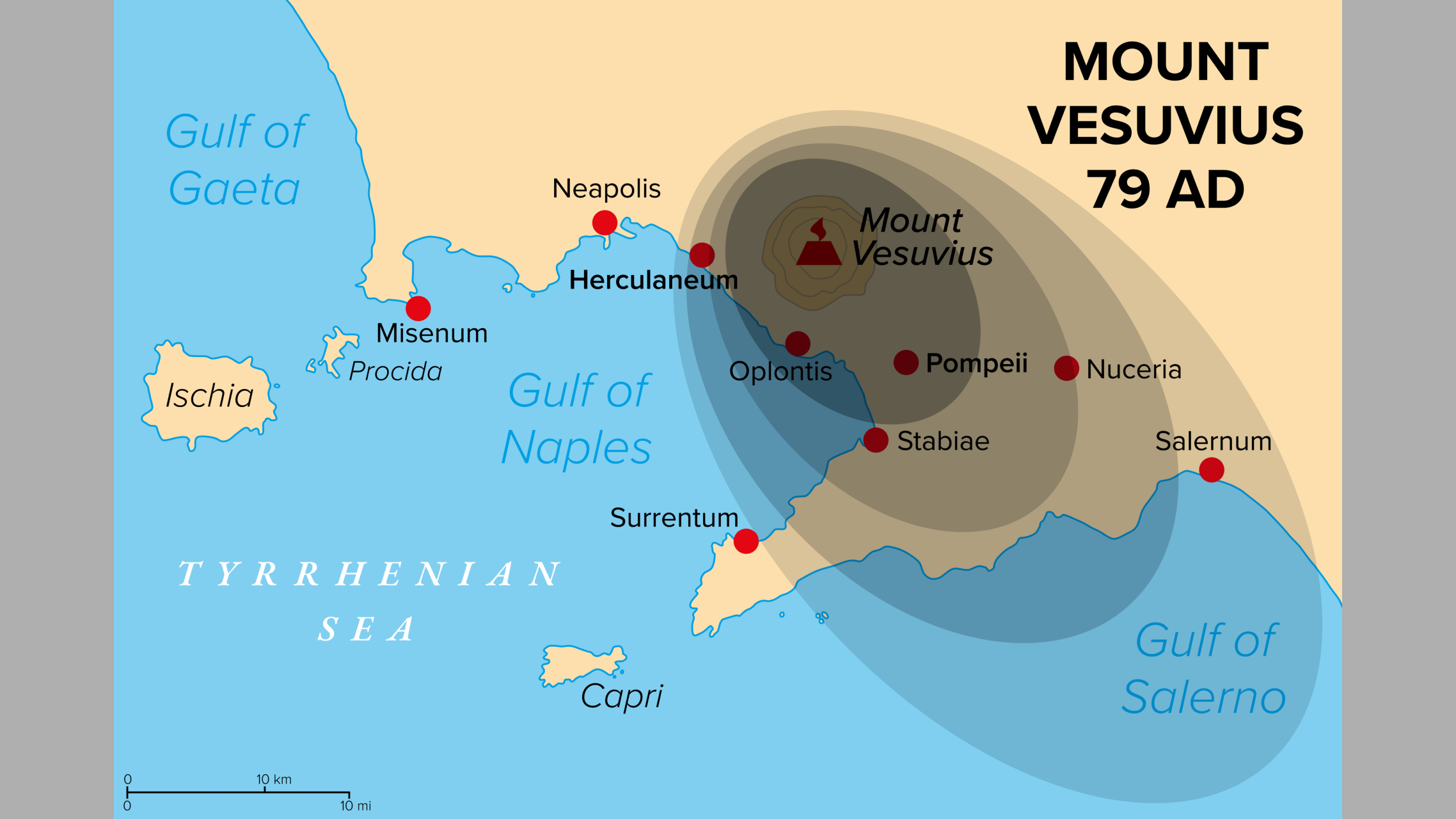

ST: We have those wonderful letters from Pliny the Younger who was about 35 or 40 miles [56 to 64 kilometers] north of the volcano watching things unfold. And he tells us that the eruption started about 1 in the afternoon with the top half of the mountain just being blown into the sky. Then slowly, as gravity overtakes the power of that explosion, that ash and pumice begins to rain down. This phase took about 18 hours. It started slowly and then built as the eruptive material came down. So for the first 18 hours, there's a lot of ash and pumice that begins to build in the sites — like Pompeii — that are southeast of the volcano, because the prevailing winds are pushing it that direction.

But Herculaneum, Pompeii's sister city, which is due west of the volcano, got none of that ash and pumice. From 1 in the afternoon till maybe 6 or 7 the next morning, very little fell on Herculaneum, just a few ashes. They had to contend with earthquakes — there were a lot of earthquakes in this eruption. The people of Herculaneum had about 18 hours to get out with nothing falling on them before the third pyroclastic surge of the eruption, which overwhelmed their city. A couple hours later, a fourth surge overwhelmed Pompeii.

So really there's a long span of time where if people reacted quickly, they could get out.

KK: People at the epicenter of the eruption are obviously noticing that stuff is happening and are able to escape. Was there a rescue effort from outside of that area? Did the Roman government realize what was happening and try to help to marshal people towards escape?

ST: There was a government response: both a local one, as well as from outside.

Locally, the people in Herculaneum and Pompeii seem to have responded. A lot of public buildings are open, and the people that did stay too long and perished are found in public buildings. So it seems like the local government is responding — but the most important response is from the Roman Navy.

Pliny the Younger, who wrote these wonderful letters or eyewitness accounts from the naval base at Misenum about 30 miles [48 km] north. He tells us that his uncle saw the eruption take place from their villa and initially planned to go and investigate it as a scientific phenomenon, until a message reached him from someone's villa that they needed rescue. He then launched this massive rescue operation with the main branch of the Roman fleet.

I mean, battleships are going out to try and save these people. It's really an extraordinary story and he responded apparently very rapidly to the eruption and tried to save people.

KK: That makes me think of the middle part of your book, where you discuss the stuff that is missing from Pompeii and Herculaneum, which suggests that people were escaping. You describe it as "evidence from absence." What does that mean, and what kind of "absent evidence" proves that there were survivors?

ST: A lot of things have been found at Pompeii. You cannot even imagine all the material that's pulled out. I've been in the store rooms and found tens of thousands of pieces of bronze. It's just extraordinary. But when you start to look at the site, what you see is that a lot of things aren't where they're supposed to be.

For example, almost every house and commercial building would have a shrine to the gods of that establishment — to the gods of the house or the gods of the business. By my count, there were at least 738 shrines in houses and shops. But in these 738 shrines, objects were found in only 18 of them. So that means that almost 98% are empty.

Now, some of these objects from the shrines, little statuettes of household gods, have been found on the bodies of people who were discovered near the gates of Pompeii. It seems very clear that people scooped up things they cared about.

The strong boxes where people kept their valuables, silver table service that they could use for currency as well as cash — those are almost all completely empty. Out of the perhaps 1,000 horse stalls that I've counted up at different stables, they're all empty. Only 12 skeletal remains of horses are found on the site of Pompeii.

Looking at the evidence for things people would grab gives you a really good sense that people did have time to take things that were valuable, things that were personally significant like their household gods, and to find means of transportation. All the boats and all the horses and mules and donkeys are all gone.

Pliny tells us that when the ash starts to come down and they lose visibility, people are wandering through the streets shouting for their families — men for their wives and women for their children. They're making a definite attempt to collect their families before they flee

KK: What historical evidence have you found of people who escaped, and are there any particular individuals or families that you can trace after they got out?

ST: This whole endeavor is only possible because Romans used family names the way we do. They have a persistent family name that you can trace as well as first names. Now, some of them are very common family names. But, when they're all named the same thing, and then they move to a new community, suddenly it's possible to track them.

One of the best examples — and one of my favorites — is a family from Pompeii called the Umbricius family. It's a very rare surname. Every male in the Umbricius family at Pompeii is named Aulus as his first name, and every other branch of the family uses a different personal name. So we have at Pompeii this family of Aulus Umbricius. Suddenly, in the post-eruption period, they appear at Puteoli, which is about 25 miles [40 km] north of Pompeii on the other side of the volcano. It was lightly damaged by the eruption but largely untouched.

We have the best evidence for this family from their names because they were merchants of "garum," the characteristic Roman fish sauce. We have labels on their products, and we have mosaics, tomb inscriptions — all sorts of things — where their names appear. Suddenly, the eruption occurs, and then just as quickly the Aulus Umbricius family appear at Puteoli. It's fascinating that the firstborn son at Puteoli is named Aulus Umbricius Puteolanus. It's like an immigrant coming to the States and naming their firstborn child America.

They restarted their garum business, and we can tell because the label changes. Instead of "this is the flower of garum made with the best ingredients by Aulus Umbricius at Pompeii," now it reads "this is the flower of garum made from the best ingredients by Puteolanus." They just use the same formula and put the son's name in there.

They were easy to trace, thankfully, due to an obscure name and a very persistent naming practice. That to me is a really interesting story, that they're picking up and rebuilding and carrying on.

KK: It's fascinating that you could trace the Umbricii directly from Pompeii to Puteoli. But what do we still not know? Who is still missing, either from the historical records of the survivors, or from the casualties whose bodies we see in Pompeii?

ST: I suspect that the vast majority of people got out, because we have so few remains: 1,200 sets of remains at Pompeii and 300 at Herculaneum, which is not a lot given the combined population of the two cities is probably about 40,000.

I think most people who fled would have moved to where they had family, and I haven't figured out yet how to trace those people [because their surnames are the same]. If my house burned down and I moved in with my brother, that would not change the naming profile in the community. And so I think the majority of people are a little invisible using this methodology.

I also have been completely stymied in my attempts to find people without Roman family names. There's a lot of good evidence that there was a Jewish community at Pompeii, and Jewish people in the ancient world don't have family names; they have a patronymic. Joshua Ben Joseph is a classic example. And that means I can't trace them unless they happen to say where they're from.

Of the escapees, just a handful, maybe literally two or three, actually say where they came from. Most people seem to pick up and move and try to integrate in their new community. They don't spend a lot of time referring back to their previous community. So I haven't found the people that I think moved in with family, and I haven't found the people without last names.

KK: That makes me think of some news that we covered at Live Science this summer, where archaeologists at Pompeii found potential evidence that people returned after the eruption and basically squatted there, on top of the ash.

ST: I was really pleased to see that report, and I think it makes absolute sense. Pompeii was largely covered by ash and pumice, which is easy to dig through. Pompeii was also only covered up to about 30 feet [9 meters], which means that the highest of the public buildings would still be sticking up, like the top of the amphitheater. When they excavated the amphitheater in the 18th century, for example, the stone seats were all removed from the upper layers. I think people came back and quarried the easily removable stone on the second and third floors and took them away to be reused, because it's good quarried stone.

The squatter community makes perfect sense, and they might have been farmers because the volcanic material is incredibly fertile. But I don't think it was ever very large. All the springs and sources of water were now 30 feet down, the river got diverted, the coast was further away after the eruption, and the aqueduct was broken. So it wouldn't have supported a large community.

KK: What's next for your research?

ST: I need to just buckle down and tackle Rome. The one city I have not looked for survivors in is Rome. It's huge. And the vast majority of the survivors I found stayed within 25 miles. They moved to the edges of the destruction and rebuilt their communities. But I think that people might have gone to Rome, and that's going to be a bigger task to look for people there. That's probably going to involve some statistical analysis.

I also want to consider the role of religion in these people's lives. There's a curious phenomenon in the post-eruption period where suddenly we find new temples to Isis being built in communities where these people resettled. There's a temple to Isis for the first time at Ostia, which we know is dedicated by one of the refugees from Pompeii.

I wonder if these people are spreading their religious beliefs as they go. That's something we see in refugee communities around the world today. I think of the Muslims of Bowling Green, Kentucky, who came out of the Bosnian War. They brought with them their religion, their food and their culture. So I'm looking at these cultural shifts that are occurring, wondering how much these are due to or maybe just jumpstarted by survivors.

I want to give a shout out to these people who made it out after Vesuvius erupted and rebuilt their lives. I focused on the merchants because they leave a lot more traces, but there were also some very poor people that made it out. I traced one of these survivors: Avianus Felicio. He becomes a foster child of a desperately poor family from Pompeii called the Masuri. It means these survivors are taking in a person who is very clearly an orphan from their community whose family didn't make it out and has no other place to go.

It's kind of a nice human story, and it's a little hopeful to me that in this time of crisis, these people are banding together and supporting each other. And that's a really intriguing idea and one I like to hang on to.

Escape from Pompeii: The Great Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Its Survivors — $29.99 on Amazon

By asking new questions about Pompeii and innovatively examining the evidence, Escape from Pompeii proves the survival of Pompeians and Herculaneans after the eruption. It sheds new insight into their lives, pre- and post-eruption, and provides new conclusions about the Roman world and its response to unimaginable suffering.

Pompeii quiz: How much do you know about the Roman town destroyed by Mount Vesuvius?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus