Pompeii victims died in 'extreme agony,' 2 newfound skeletons reveal

Archaeologists have found the skeletons of a man and a woman, along with their valuables, in a room in Pompeii.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists have found the skeletal remains of a woman and a man who died when the volcanic plumes of Mount Vesuvius wiped out the city of Pompeii nearly 2,000 years ago.

The findings provide a glimpse of the final moments of the people who attempted to escape the ancient Roman city, the archaeologists said.

Pompeii was an exuberant resort city south of modern-day Naples. The city sat about 6 miles (10 kilometers) from Mount Vesuvius, which is still considered an active volcano today. Scholars estimate that around 10,000 to 20,000 people inhabited the city when the volcano famously erupted in A.D. 79 and that 2,000 likely died from the pyroclastic flow — hot volcanic gas, lava and ash — within 20 minutes of contact.

Details of the recent discovery of the two victims were published Monday (Aug. 12) in the E-Journal Scavi di Pompei (Pompeii Excavations).

"Even after two millennia, we encounter the suffering and anguish of the people who perished, and it is our duty to address these with sensitivity and precision," Gabriel Zuchtriegel, an archaeologist and director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, said in a translated video.

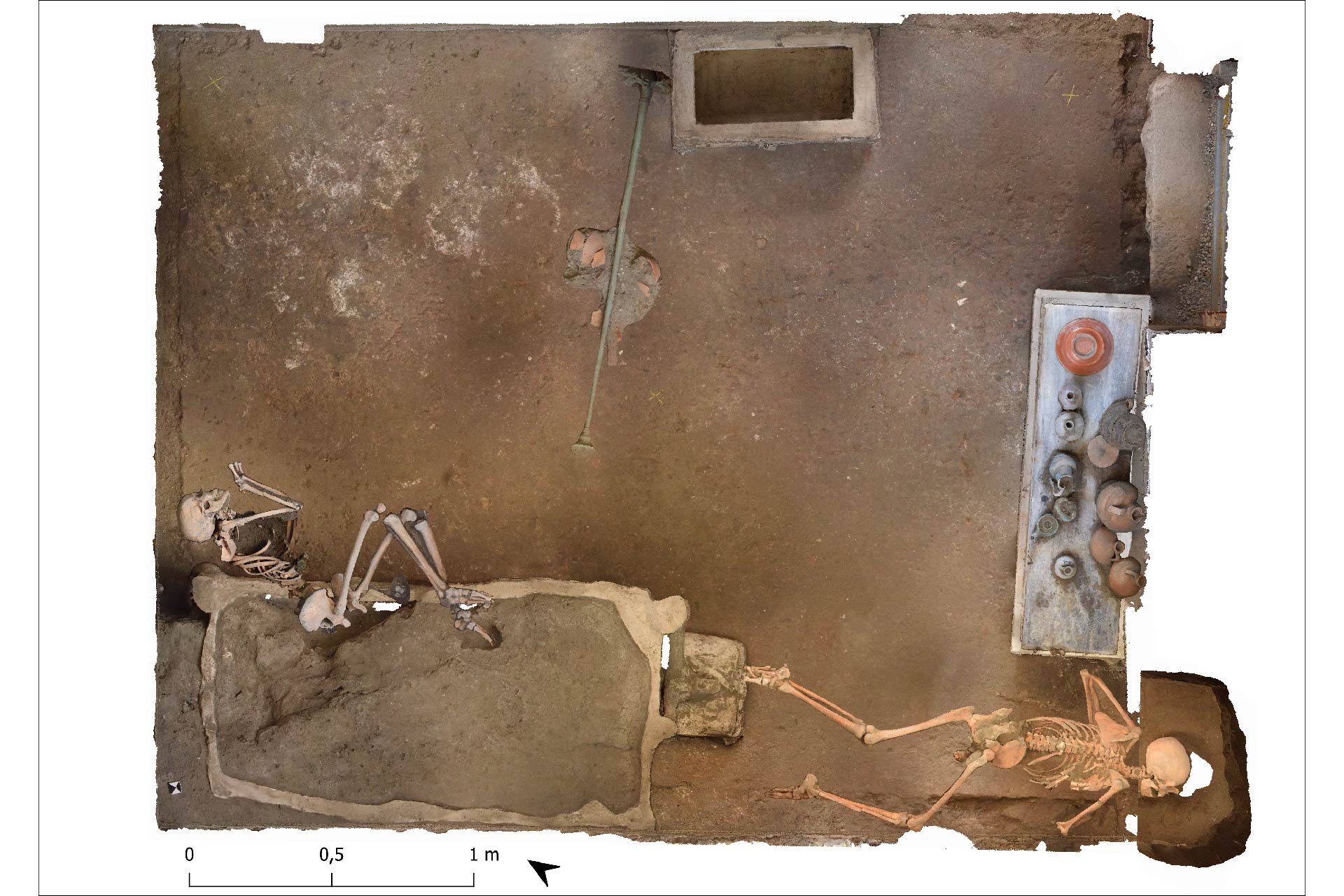

Archaeologists found the skeletal remains in a 9-by-11.5-foot (2.8 by 3.5 meters) room in a house that they began excavating in 2023. Despite the relatively small area, the excavation was complex, Zuchtriegel and his team wrote in the translated article. Because the skeletons and objects were very delicate, the task "necessitated meticulous microscale excavation and removal work," they wrote in the study.

Related: Evidence of more than 200 survivors of Mount Vesuvius eruption discovered in ancient Roman records

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

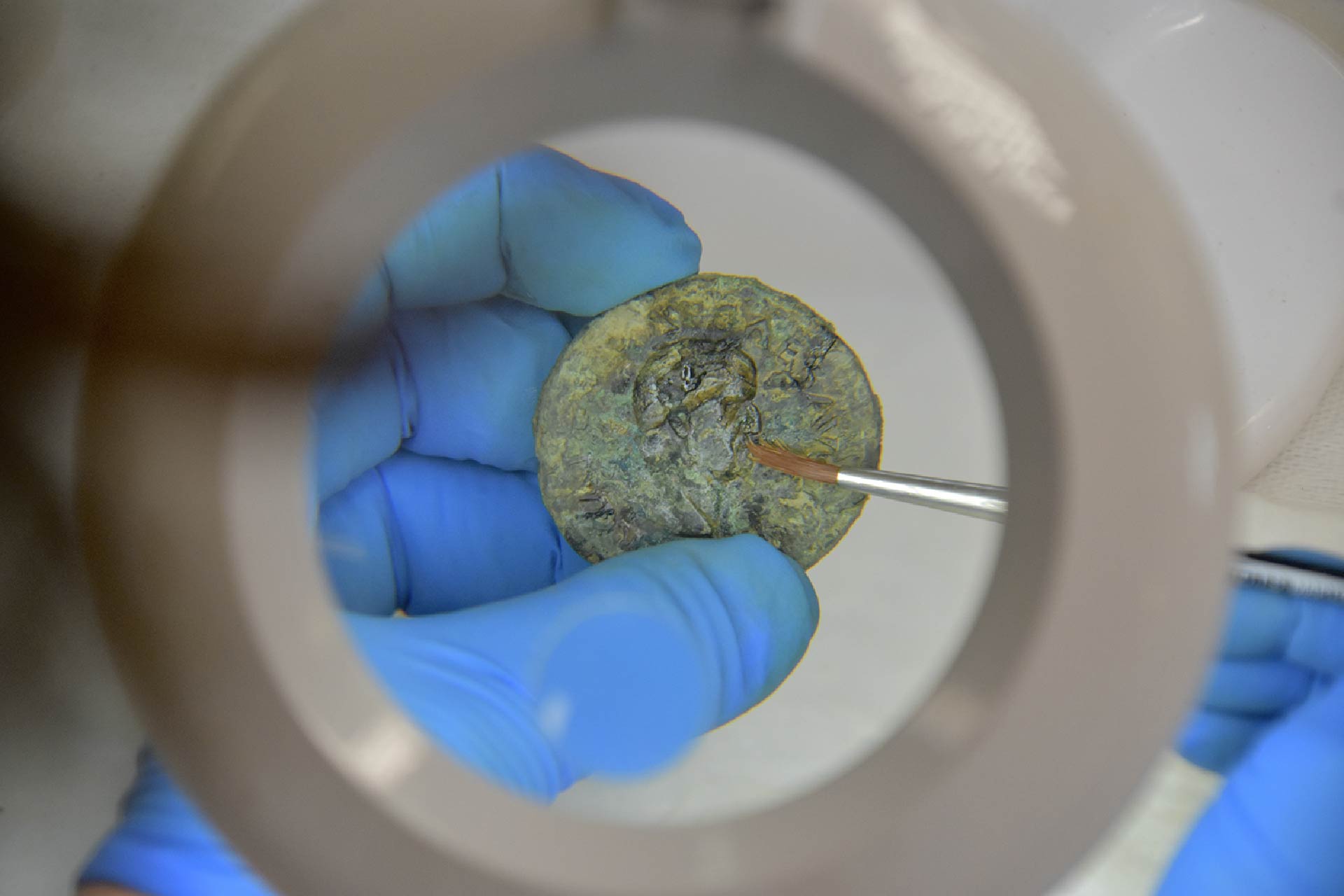

The woman's skeleton was lying near a bed with a handful of treasures, including gold, silver and bronze coins and a pair of gold-and-pearl earrings. She also had a key, which may have been connected to a small chest across the bed — suggesting a possible attempt to retrieve valuables moments before she tried to escape. Based on analyses of her pubic bones and teeth, she was about 35 to 45 years old when she died.

The young man, who was 15 to 20 years old when he died, was crushed by the collapse of a wall and trapped in another corner of the room in a very tight space. He was next to what seemed like an exit. The relationship between the woman and the man is unknown.

Aside from the bed and the chest, the archaeologists found a three-legged stool and a wooden service table with a marble top cluttered with glass, bronze and ceramic tableware and lamps. By pouring plasters into the cavities of the remnants, the archaeologists were able to reconstruct the furniture. The imprints on the volcanic deposits marked the original positions of the items.

"The opportunity to recognize the victims and their choices to seek refuge or attempt to escape, to take certain objects with them and leave others behind, reveals a shared humanity," the archaeologists wrote in the study. Sometimes, we "forget that for the ancients the catastrophe must have been even more monstrous and inconceivable than we can imagine today, given that they did not understand exactly what volcanoes were or what caused earthquakes."

The excavation is part of a larger project intended to uncover the archaeological site. New projects are set to begin outside the walls of Pompeii soon, according to a statement from the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. Several discoveries have been made at Pompeii in recent years, including a skeleton of a man fleeing the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, a still-life fresco of a meal and an inscription describing a gathering.

"It is not just an archaeological study or art history but a way to understand the human suffering witnessed in Pompeii," Zuchtriegel said.

Kristel is a science writer based in the U.S. with a doctorate in chemistry from the University of New South Wales, Australia. She holds a master's degree in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work has appeared in Drug Discovery News, Science, Eos and Mongabay, among other outlets. She received the 2022 Eric and Wendy Schmidt Awards for Excellence in Science Communications.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus