Hadrian's Wall: The defensive Roman wall that protected the frontier in Britain for 300 years

The wall is the largest Roman archaeological feature in Britain and was built to defend the northernmost limit of the Roman Empire.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Name: Hadrian's Wall

What it is: A defensive wall built by the Romans that once guarded the empire's northernmost frontier in England.

How long is Hadrian's Wall: 74 miles (118 kilometers)

When was Hadrian's Wall built: A.D. 122

Hadrian's Wall served as the most northerly frontier of the Roman Empire for 300 years. The wall is located in northern England, runs for about 74 miles (118 kilometers) between Bowness-on-Solway in the west and Wallsend in the east.

Construction started around A.D. 122, after a visit to Britain by Emperor Hadrian (reign A.D. 117 to 138), who was determined to consolidate the Roman Empire's borders. England and Wales had both fallen to Roman control by A.D. 61 when the Iceni queen, Boudica, was defeated. Scotland, however, had successfully resisted Roman attempts at conquest thanks to a people called the "Caledonians" who thwarted attempts by Roman legions to take permanent control of the Scottish lowlands.

The wall was Hadrian's attempt to establish a defensible border between southern Britain and the unconquered north. Built using local materials by Roman soldiers from the II, VI and XX legions, the wall's initial fortifications were finished within a few years and were staffed mainly by auxiliary (non-Roman citizen) units.

The wall would have made a strong impression on the local people, to say the least.

"We have to envisage an area of Britain where there wasn't all that much stone building, certainly no monumental masonry, so it would have been a totally alien thing," Miranda Aldhouse-Green, an emeritus professor in the School of History, Archaeology and Religion at Cardiff University said in a 2006 BBC Timewatch documentary. "It would be like a visitation from another world and people would be gobsmacked by it."

How long is Hadrian's Wall?

Ancient history researcher Nic Fields noted that, when originally constructed, the eastern portion of the wall was built of stone and ran for 41 miles (65 km), ending at Newcastle upon Tyne. Eventually this was expanded further east to Wallsend. It measured about 10 feet (3 meters) wide and perhaps 15 feet (4.4 m) tall.

The western portion of the wall, on the other hand, was made of turf and extended for 29 miles (47 km), ending at Bowness-on-Solway. Its width was about 20 feet (5.9 m).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Turf was a building material that was tried and tested and its use in the western sector might indicate a need for speed of construction," Fields wrote in his book, "Hadrian's Wall A.D. 122-410" (Osprey Publishing, 2003).

To the north of Hadrian's Wall was a V-shaped ditch, and to the south was another line of defense called the "vallum," which was constructed gradually. The vallum consisted of a ditch flanked by "large earth ramparts or mounds, according to Newcastle University archaeologist Rob Collins, who wrote "Hadrian's Wall and the End of Empire" (Routledge, 2012).

A milecastle, a small gateway that could house a few soldiers, was positioned about every mile of the wall. There were two turrets between each milecastle. In addition, large fortresses were built about every 7 miles (11 km) apart.

These fortresses were up to 9 acres (3.6 hectares) in size, were shaped like a "playing card," and had all the necessary support facilities.

"Important buildings such as the principia (headquarters building), praetorium (commanding officer's house), and horrea (granaries) were found in the central range, with the front and rear ranges containing barrack accommodation and other structures," Collins wrote.

Women at Hadrian's Wall

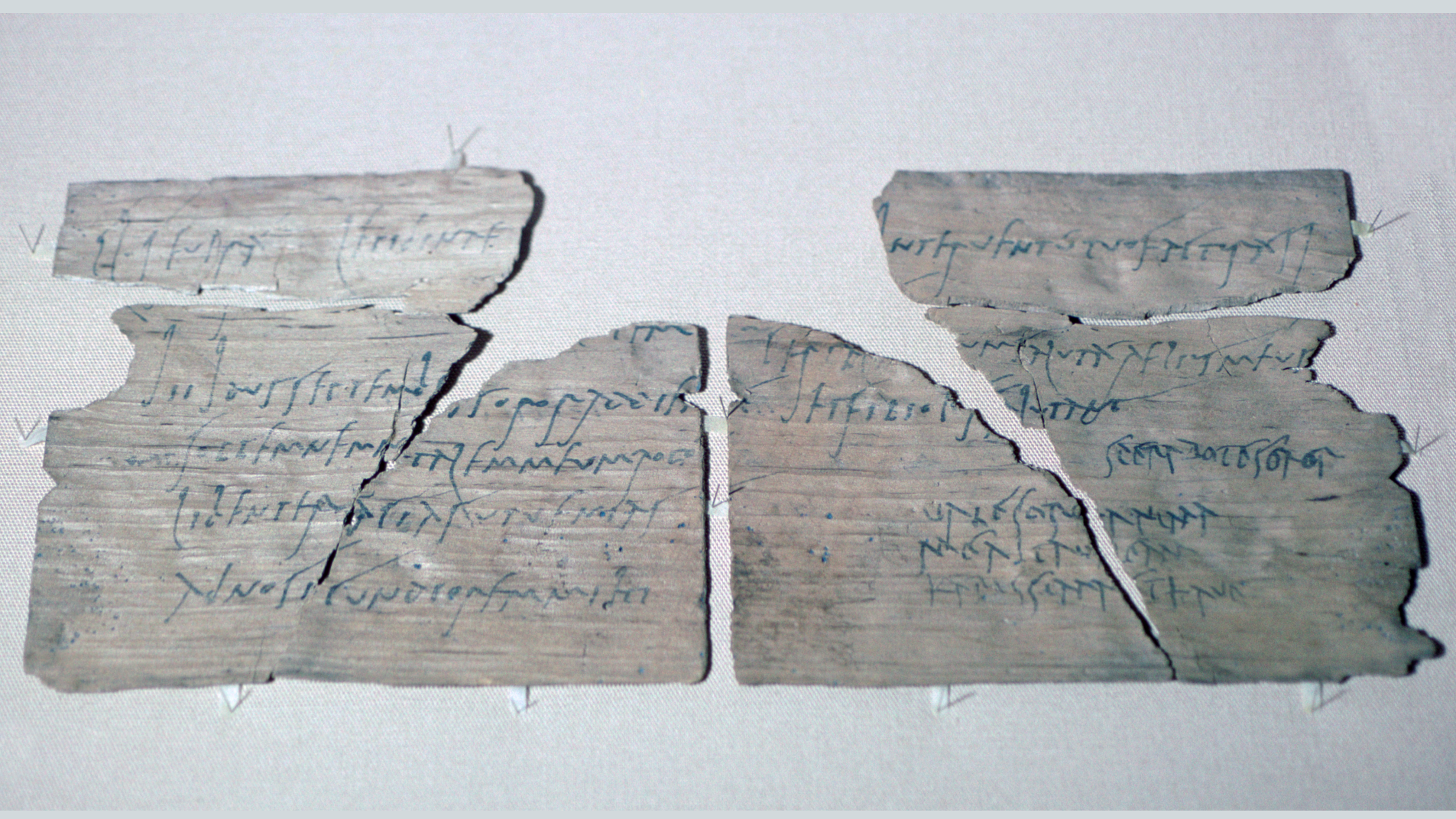

At Vindolanda fort, hundreds of wooden tablets with handwritten Latin writing have been unearthed, providing glimpses into the everyday lives of the soldiers stationed there. This particular fortress was in use before and during the time of Hadrian's Wall.

The texts reveal that senior military commanders at Vindolanda had wives, and the tablets reveal a correspondence between two women, Sulpicia Lepidina and Claudia Severa. The two were isolated by their sex and social status, and they may have been lonely.

"The letters between them deal with little things such as invitations to come and visit: Claudia, for example, invites Sulpicia to visit her on her birthday," Geraint Osborn wrote in his book, "Hadrian's Wall and its People" (Liverpool University Press, 2006).

"I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival..." reads part of the invitation from Claudia (translation from "Vindolanda Tablets Online," Oxford University).

The wives of lower-ranking soldiers on Hadrian's Wall fortresses had to be more discreet.

"Men of lower ranks were forbidden to marry; they should have no ties to the area, so that they could be rapidly posted elsewhere," Osborn wrote. "However, whatever the prohibitions, ordinary soldiers did contract illegal marriages, often keeping wives and kids" in the civilian settlements adjacent to the fortresses."

Daily life at Hadrian's Wall

The same soil conditions at Vindolanda that preserved writing tablets also preserved leather goods from Roman times, providing new clues to the everyday lives of soldiers and their families.

More than 7,000 preserved leather items have been discovered at Vindolanda to date, including tent panels, saddles and bags, according to the Vindolanda Archaeological Leather Project. Most of these leather items are shoes of all shapes and sizes that belonged to men, women and children.

According to the project website, the shoes are "particularly important for our understanding of life in a military fort and settlement such as Vindolanda, because it was believed for a long time that military settlements were inhabited only by men."

Excavations at another fort along Hadrian's Wall, called Magna, produced some of the largest leather shoes ever seen at a Roman site. The eight XXL shoes are the equivalent of a men's size 14 US (size 13 UK). While the shoes might suggest that the soldiers at Magna were extraordinarily tall, another interpretation is that they were layering socks and sandals to keep out the bitterly cold and wet British weather.

Vindolanda has also surprised archaeologists with toy swords, which were likely used by soldiers' kids, as well as the first evidence that bedbugs hitched a ride with Roman legions to infest their settlements as they conquered Britain.

Hadrian's wall through time

As Rome's military position in Britain changed, so did the wall.

After Hadrian's death in A.D. 138, his successor Antoninus Pius (reign A.D. 138 to 161) adopted a radically different policy in Britain. He abandoned Hadrian's Wall and made a concerted effort to conquer the Scottish lowlands. After having some success, he built a new line of fortifications in Scotland known as Antonine's Wall.

Antoninus' conquest proved only temporary and, by the end of his reign, the Scottish fortifications were abandoned and Hadrian's Wall was reoccupied.

A series of modifications were then made to the wall, including the replacement of the turf portion in favor of stone and the construction of a road called the "military way" to the south of the wall. In addition, Collins noted, the turrets appear to have been decommissioned and the gateways of the milecastles narrowed.

As time went on, more changes occurred. In the fourth century, as the Roman Empire came under greater military pressure, Collins noted that the gates of the milecastles were narrowed further and some blocked off altogether.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century and the beginning of the Dark Ages, the political landscape of Britain changed, and the wall became "politically redundant," Collins wrote. Its fortifications were quarried for stone, and some of them were used to help build England's medieval castles, which served as the country's new premier fortifications.

One particular spot along Hadrian's Wall has been a popular photography spot for decades: Sycamore Gap. A large sycamore tree grew next to the dramatic dip in the wall for over 150 years. In 2023, the tree was illegally felled, and the men responsible were charged with criminal damage to the tree and to Hadrian's Wall.

Editor's note: This piece was originally published on Nov. 1, 2012 and updated on Aug. 4, 2025 to include information about daily life at Hadrian's Wall and the sycamore tree that was illegally felled in 2023.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus