'We have basically destroyed what capacity we had to respond to a pandemic,' says leading epidemiologist Michael Osterholm

Live Science spoke with leading epidemiologist Michael Osterholm about his new book, "The Big One," which discusses the next pandemic and how to mitigate its harm.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

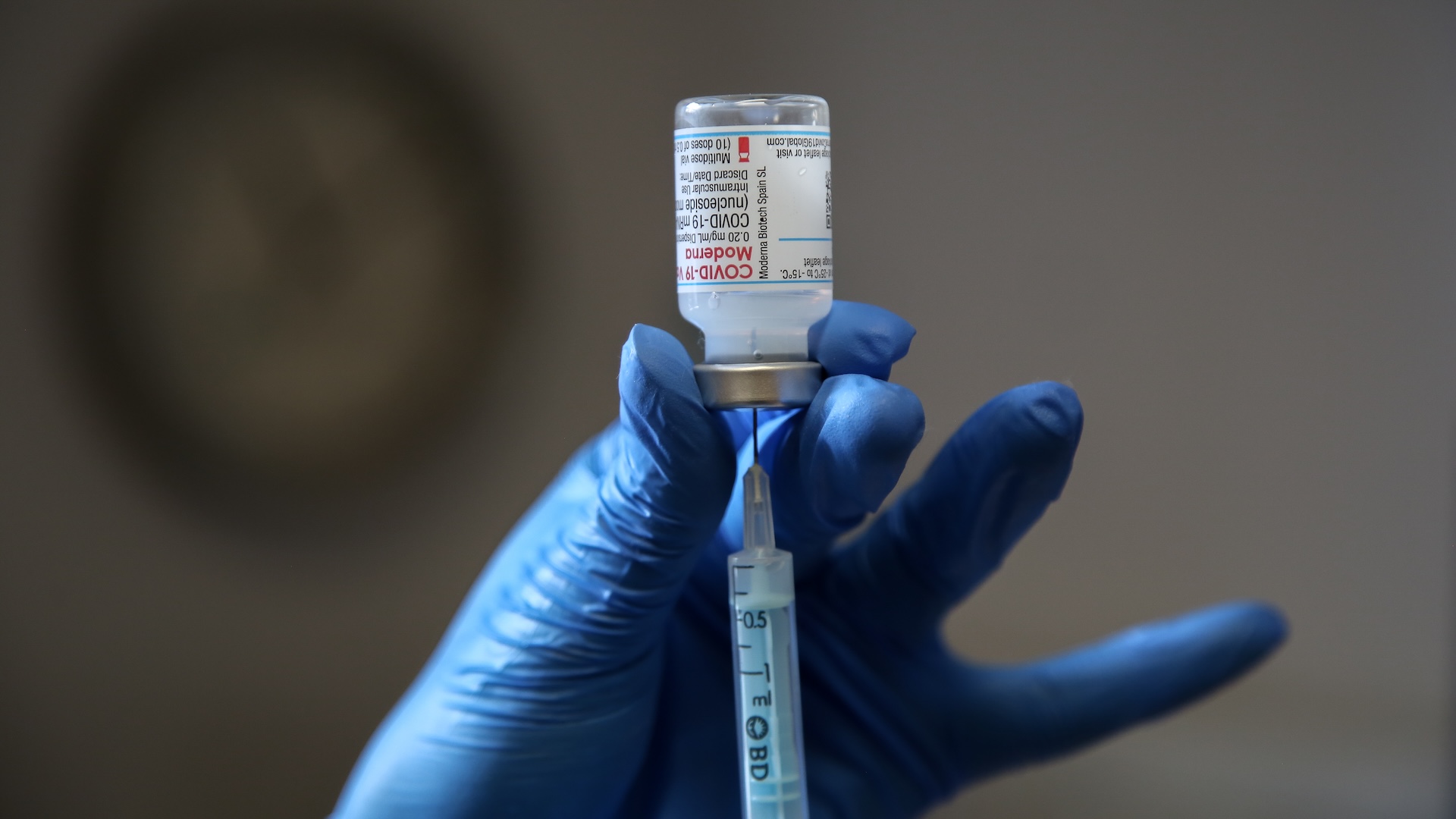

COVID-19 has claimed the lives of more than 7 million people across the world, to date, including over 1 million people in the U.S., according to the World Health Organization. In addition to this staggering death toll, the disease has unleashed a wave of chronic illness, and at the peak of the pandemic, it triggered widespread disruptions in supply chains and health care services that ultimately threatened or ended people's lives.

Since its emergence in 2019, the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has had a tremendous impact on society. And yet, the next pandemic could potentially be even worse.

That's the argument of a new book by Michael Osterholm, founding director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota, and award-winning author Mark Olshaker. The text doesn't just serve as a warning. As suggested by its title — "The Big One: How We Must Prepare for Future Deadly Pandemics" (Little Brown Spark, 2025) — the book lays out lessons learned during past pandemics and points to actions that could be taken to mitigate harm and save lives when the next infectious disease outbreak tears across the globe.

Notably, the text was finalized before President Donald Trump began his second term.

Since then, "we have basically destroyed what capacity we had to respond to a pandemic," Osterholm told Live Science. "The office that normally did this work in the White House has been totally disbanded."

Live Science spoke with Osterholm about the new book, what we should expect from the next pandemic and how we might prepare — both under ideal circumstances and under the current realities facing the U.S.

Related: RFK's proposal to let bird flu spread through poultry could set us up for a pandemic, experts warn

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nicoletta Lanese: Given the book's title — "The Big One" — I figured we could start by defining what you mean by that phrase.

Michael Osterholm: Having worked, as I have, with coronaviruses, there are two characteristics that become very important: One is, how infectious are they? How relatively able are they to transmit? And [two], how lethal are they? How serious is the illness that they create, and the number of deaths?

I worked on both SARS and MERS before COVID came along. [SARS and MERS are severe coronavirus infections that predate COVID-19.] Those were two viruses that basically had the ability to kill 15% to 35% of the people that it infected, but they weren't nearly as infectious because they didn't have the ACE receptor capacity. [SARS-CoV-2, in comparison, plugs into the ACE2 receptor on human cells.]

But then along comes COVID, which basically has this highly infectious characteristic but fortunately, the case-fatality rate and serious illness was substantially lower than what we saw with MERS and SARS. Just in the last six months, there's actually been the isolation of new coronaviruses from bats in China that actually have both [high infectiousness and high lethality] now. They actually have the ACE receptor capacity as well as that segment of the virus that was responsible for causing such severe illness.

So imagine a next pandemic where it's as infectious as COVID was, but instead of killing 1% to 2% of the people [it infected], it killed 15% to 35% of the people. That's exactly the example we're talking about with The Big One.

The same thing is true with influenza. You know, we've not seen a really severe influenza pandemic dating back to 1918, relative to what it could be. And clearly there are influenza pandemics there, in a sense, waiting to happen. In the future, someday, that could easily be similar to or worse than what we saw with 1918 flu.

So we're trying to give people a sense that nobody's dismissing how severe COVID was, or what it did. It was devastating. But devastating with a "small d," not a "capital D," when you compare it to what could happen.

NL: You mentioned both coronaviruses and influenza. Do you think the pathogen that sparks the next pandemic will belong to one of those groups?

MO: We refer to these as "viruses with wings" in our book — you have to have a "virus with wings" to really make it into the pandemic category. I don't think there's a bacteria right now that would fit that characteristic; it really is in the virus family.

The greatest likelihood is going to be an influenza [virus] or coronavirus. Sure, there could be a surprise infection that comes up, but it'll have to have characteristics like flu and coronavirus in the sense of respiratory transmission.

NL: Could you clarify what you mean by "virus with wings?" What gives a virus pandemic potential?

MO: One of the things that made, for example, SARS and MERS easier to contain was for many of the [infected] individuals, they did not become highly infectious until after they're already clinically ill. But with COVID, we saw clearly a number of people who were actually infecting others when they were still asymptomatic, or they remained asymptomatic.

It [a "virus with wings"] has to have the airborne transmission capability, and that's the key one right there. … It would also be a virus that is novel to the society and that wouldn't have pre-existing immunity.

NL: You make the case in the book that you can't necessarily prevent a pandemic pathogen from taking off, but you can mitigate its harm. Why is that?

MO: I think exactly why we give the reader the scenario, because you can see the conditions on the ground in Somalia. [Editor's note: Throughout "The Big One," the authors return to a thought experiment in which a pandemic virus emerges in Somalia and then spreads around the world, despite efforts by health officials to contain it.]

Every city, every camp, every clinic, every health care-related event is actually real. But you can see very quickly how a virus that emerged from an animal population — in this case camels — got into humans and how fast it moved around the world before anybody recognized it.

mRNA technology offered us a real hope that we could actually, in the first year, have enough [vaccine] for the world. And of course you saw that was all just taken off the shelf by the White House.

Michael Osterholm, University of Minnesota

These viruses are by nature highly infectious, and in a very mobile society, they are going to move. It just again illustrates that once that leaks out, it's out, it's gone. You can't unring a bell. Whereas other diseases that may be much slower to emerge and less likely to cause widespread transmission, you might be able to get to, but not easily with the pandemic. It's just gone. That's "wings," right there.

NL: And when you talk about mitigating pandemics, you make the point that governments must be involved, that industry can't do it alone. Why?

MO: Let me just say: I regret we didn't have six more months on this book. So many things have changed even from the time that the last manuscript went in at the end of last year and now, just because of what's happened in the Trump administration. We have basically destroyed what capacity we had to respond to a pandemic. The office that normally did this work in the White House has been totally disbanded [that being the Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy]. And there's no expertise there.

Today, if we had a major influenza pandemic and we needed vaccine, we'd be using the embryonated chicken egg, which is the only means we have for any large-volume production of vaccine. Novavax has a cell-based one, but it's very limited how much can be produced. Even with all the global capacity, we could only make enough vaccine in the first 12 to 18 months for about one-fourth of the world. So three-quarters of the world in the first year of the pandemic wouldn't even see a vaccine, and it would take several years more.

Well, mRNA technology offered us a real hope that we could actually, in the first year, have enough for the world. And of course you saw that was all just taken off the shelf by the White House. HHS [the Department of Health and Human Services] said no more, $500 million is down. The money had been given to Moderna to actually develop prototypes ready to go so that if we needed them, we wouldn't have to go through the long laborious process of getting them approved. We get them approved now with the strain change issue [left for when a pandemic virus emerges].

And suddenly, that is like losing one of your wings at 30,000 feet [9,100 meters] — it's a devastating situation.

NL: To push the point on mRNA: Do you see its main advantage being the speed of vaccine production?

MO: What's important here with mRNA technology is in fact the speed, and you nailed that. Both in terms of not only designing the vaccine, but making it.

The second thing about it, though, is because of the way you can insert specific antigens into these vaccines [proteins that look foreign to the immune system]. You can take any one piece or several pieces, and actually now there's work going on on multiple antigens into mRNA vaccine, and that would be even better.

So it's much easier [than conventional vaccine manufacturing]. It's like a plug-and-play. Before, we didn't have anything like that. And clearly, we've demonstrated the mRNA approach does cause the human immune system to respond just as we want it to.

NL: You also spend a lot of time in the book on the topic of communications — namely, how to better communicate key information in an unfolding pandemic. What do you think is a central takeaway for communicators?

MO: Science is not truth; science is the pursuit of truth. So expect that we're going to learn a lot over the course of time. And I wish I could say to you today what I'll know three years from now, but I'm not. So the best I can do is keep you informed.

You know, I wrote an op-ed piece in the Washington Post early in the pandemic response before lockdowns even got going and I urged not to do lockdowns. "They won't work, don't do them. When are you going to release the lockdown, because this is going to last for months to years?"

What I suggested was something more akin to a snow day. The most important thing we could do to minimize the number of severe illnesses and deaths was to keep our health care system functioning and to be able to provide that care. Well, we didn't do that well because we have these big bursts of cases. What if we had really had the data on hospital capacity in every community, and we put those numbers up every day? And when we approached, you know, 95% of beds full: "Please, just like we do for snow days, for the next week, if you can back off public interaction, we can get those bed numbers back down." We were in this for the long haul.

We should have done a much better job of communicating that and not just jumping to "lockdowns" because when they ended, then what the hell do you do? We didn't paint this as, "This is going to be a battle for potentially three or four years." We were approaching this far too much like a hurricane situation. "It's going to blow through, it's going to be horrible, but in six hours, 12 hours, we'll be able to get to recovery mode." This wasn't going to happen that way.

One of things I find, throughout my 50 years in the business, is that people want truth. Don't sugarcoat things. At the same time, don't exaggerate; give people the reason as to how you got there.

NL: Given how complicated our information ecosystem is now, I'm not sure if you have an impression of where most people got their updates? Or if it was highly mixed?

MO: I think that's a very important point. And I would say that no one's talking about having one single unified voice, because there's going to be differences when you're pursuing [solutions] and they'll change over time.

That's where we needed more humility. I keep coming back to that word humility — to say what we know and what we don't know and how it could change. I think had we done that, we'd be in much better shape in terms of public credibility. When you don't know, say you don't know.

NL: You close the book noting that you're often asked what the average person can do. Is there anything?

MO: Actually this has come into sharper focus with regard to the vaccine issue right now.

On our website, for example, when I do the podcast, we in the show notes list organizations that are working in the community on vaccines and to help support availability, education, etc. Get engaged with them. One of the things we didn't do is use our citizen public health army during the pandemic that we could have. There were some limited outreaches, for example, to the religious, to pastors and so forth, but I think we could do much, much more. Information will not stop the pandemic, but information may minimize the horrible impact that it has.

When I talk about citizen involvement, they can't go and make vaccines, but they can surely reach out to their elected officials. They can make sure that [harmful] policies are not being made at school boards, or at city councils or in state legislatures. We just had a bill introduced in Minnesota that's starting to get some legs to it, that would outlaw mRNA technology as a criminal activity. Literally, if you gave a vaccine, you could go to prison.

Having citizens be able to track this, maintain contact and be able to testify I think is really important. … We have to do more and more, to have citizen watch groups that are alerting people.

VIP [Vaccine Integrity Project, an initiative aimed at safeguarding vaccine use in the U.S.] is a good example of this. One of the individuals who presented yesterday at our big meeting is a woman with three kids, who is a mother, a department chief, all these different things — I don't know which 29 hours a day she works, but she's amazing. I said to her, "You know, you've got to take some time off." And she said, "This is too important."

This is what's giving me hope, you know. That's what we have to tap into.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

The Big One: How We Must Prepare for Future Deadly Pandemics

"The Big One" examines past pandemics, highlighting the ways societies both succeeded and failed to address them; traces the COVID-19 pandemic and evaluates how it was handled; and looks to the future, projecting what the next pandemics might look like and what must be done to mitigate them. It's a gripping, comprehensive, and urgent wake-up call. Because COVID-19 was just a taste of what's to come — if we're going to survive the next big pandemic, we need to be prepared.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus