Collapse of key Atlantic current could bring extreme drought to Europe for hundreds of years, study finds

Scientists modeled Europe's future if a key Atlantic current were to collapse and found that the continent faces a much drier future.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Southern Europe's already scorching dry summers could get even worse over the next 1,000 years if a key ocean current system collapses — with a rise in extreme droughts and longer dry seasons, a new study suggests.

This is the first time that researchers have compared what would happen to Europe's summer precipitation under different climate scenarios if the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) were to collapse.

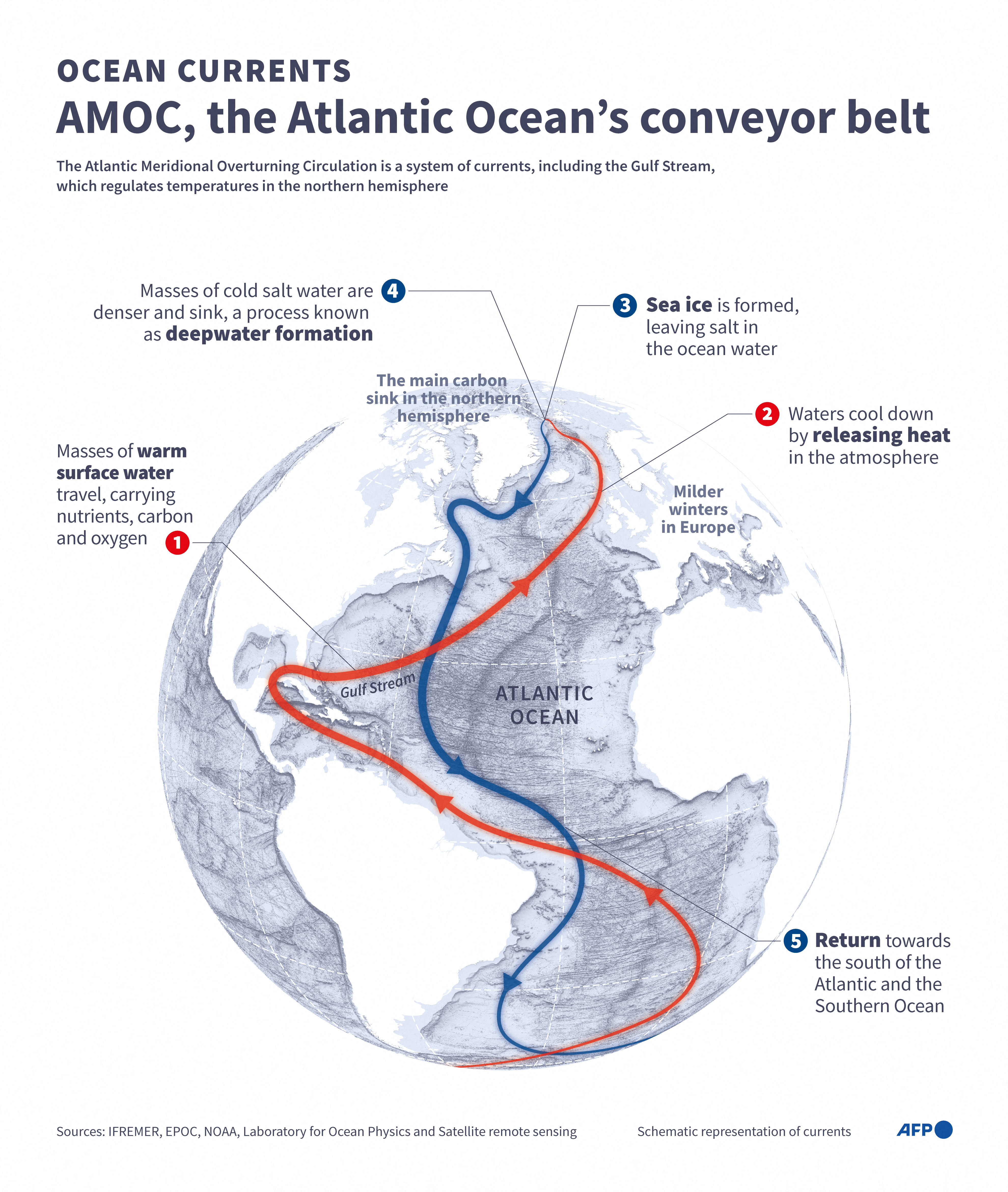

The AMOC is a major ocean current system in the Atlantic Ocean that brings heat from the Southern Hemisphere to the Northern Hemisphere and helps regulate the climate globally. Scientists have previously warned that human-linked climate change is weakening the massive current system and could be pushing it to a tipping point. (Tipping points are thresholds in Earth's climate system.)

"The AMOC actually shapes our global climate system," René van Westen, lead author on the new paper and a postdoctoral researcher in marine and atmospheric science at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, told Live Science.

These currents are why northwestern Europe has a relatively mild climate compared with southern Canada, which is at the same latitude, he said. An AMOC collapse is expected to result in much colder winter temperatures across Europe. But the AMOC also brings a lot of moisture to the continent. "The climate over Europe is both influenced by temperature, but also precipitation," van Westen said.

In the new study, the researchers ran eight simulations that extended over more than 1,000 years. Four simulations mimicked pre-industrial greenhouse gas levels, but these were theoretical because the world has already surpassed these atmospheric carbon levels.

Of the remaining four, two simulations looked at what would happen to precipitation if humanity's carbon emissions peaked in the middle of this century and then started to decline (known as RCP4.5) and small or large amounts of fresh water flooded the Atlantic Ocean.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When large quantities of fresh water flood the ocean (from melting icecaps, for example), it changes the water's salinity, density and how the water transports energy. In the RCP4.5 models, a large quantity of fresh water ultimately collapsed the AMOC, while it recovered if there was a smaller amount of fresh water.

The final two simulations modeled a high-emissions scenario, in which carbon emissions are three times higher than they are now (known as RCP8.5). The AMOC collapsed in both freshwater scenarios.

Van Westen said that two RCP4.5 options are the most realistic of the eight scenarios. "Under climate change, you're getting more evaporation and your dry season becomes drier," which is already widely known, he said. "If you add AMOC collapse on top of that, you're going to get more drought extremes."

Over the whole of Europe, dry season intensity, or the difference between how much water evaporates off the land and how much precipitation there is), increases by 8% in an RCP4.5 scenario with the AMOC still intact. But if it collapses, that intensity increases by 28%.

There is also a significant contrast between northern and southern Europe. For example, in Sweden, the dry season increases by 54% with the AMOC and 72% without the AMOC. Spain, which is already struggling with extreme drought, will see its dry season increase by 40% with AMOC and 60% without it.

These different scenarios reflect stable climates, rather than the current situation in which global temperatures are rapidly warming. "We're interested in what the mean responses are with different kinds of AMOC states in the background," van Westen said.

Karsten Haustein, a climate scientist at the University of Leipzig in Germany, welcomed the analysis of the stable state of future climates. "The beauty of these simulations is that they look at hundreds of years after everything has changed," he told Live Science.

"The transient scenario where we plan for the next 100 years is different to an equilibrium scenario. Just because we get much drier conditions in the next 50 or 100 years doesn't mean it's going to stay like this forever, depending on the scenario," he said.

The long-term view of stable conditions makes this paper "very exciting and interesting, because it gives us so much more to work with," he added.

However, Jon Robson, a professor of climate science with National Centre for Atmospheric Science at the University of Reading, U.K. who was not involved in the research, warned against using the study's theoretical results to predict future climates. "To get the AMOC to 'collapse' in this particular model, the authors need to add huge amounts of additional freshwater into the North Atlantic [and] that is not realistic," he told Live Science. "But it could be taken as a warning about what might be possible under the rather extreme scenario of an AMOC 'collapse'."

The overall message is clear, Stefan Rahmstorf, co-head of the research department on Earth system analysis at Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, told Live Science.

"The increasing drought problems expected in any case due to global warming would be made even worse by a major AMOC weakening, and the latter looks increasingly likely," said Rahmstorf, who was not involved in the study.

"If the AMOC shuts down, this would have consequences for at least a thousand years to come — a huge responsibility for the decision makers of today."

Sarah Wild is a British-South African freelance science journalist. She has written about particle physics, cosmology and everything in between. She studied physics, electronics and English literature at Rhodes University, South Africa, and later read for an MSc Medicine in bioethics.

Since she started perpetrating journalism for a living, she's written books, won awards, and run national science desks. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science, Scientific American, and The Observer, among others. In 2017 she won a gold AAAS Kavli for her reporting on forensics in South Africa.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus