Shapeshifting 'braided river' in Tibet is the highest in the world, and is becoming increasingly unstable — Earth from space

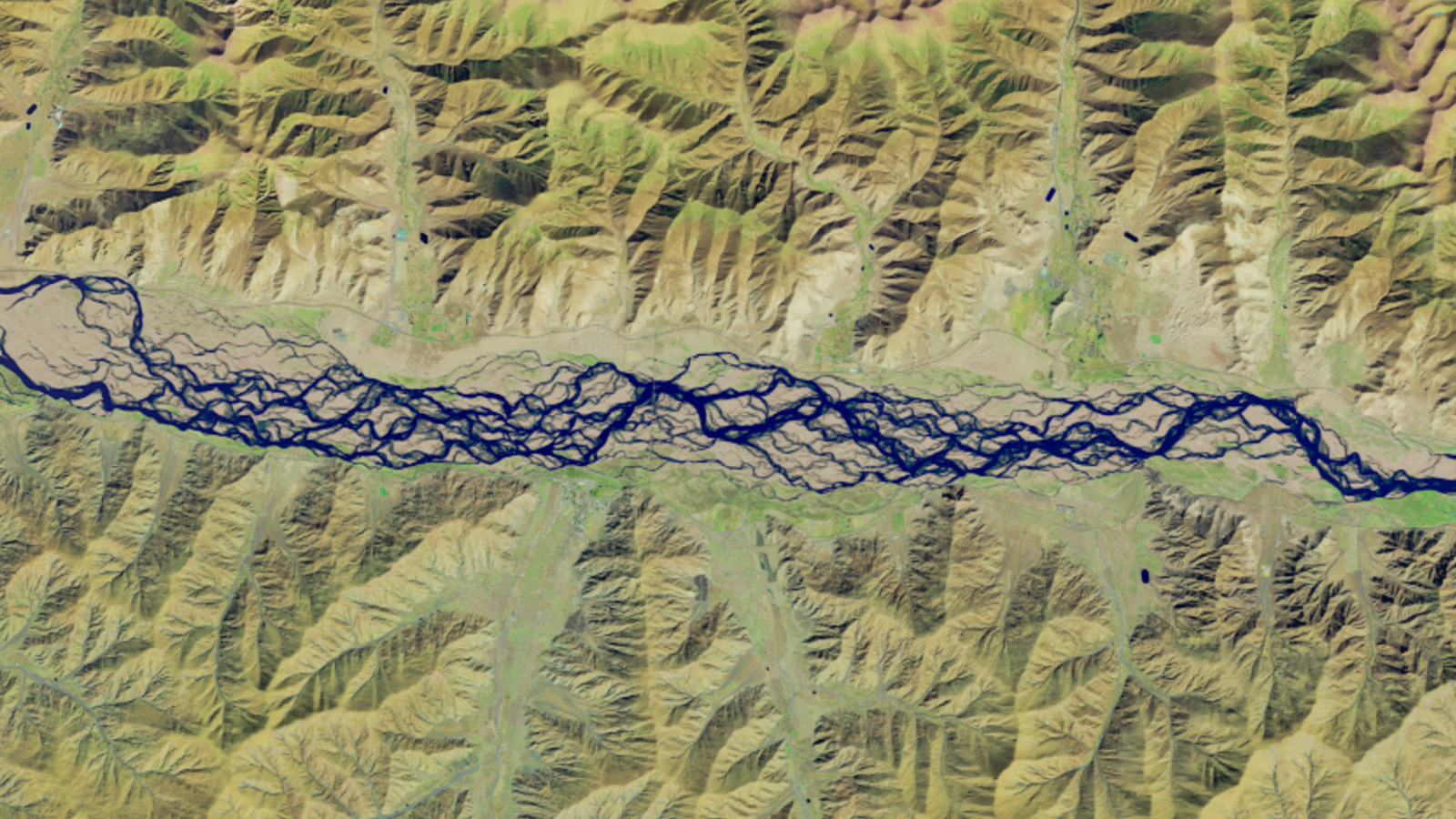

A 2025 satellite photo shows a particularly complex section of the Yarlung Zangbo River as it twists its way through the Tibetan Plateau. This part of the "braided" waterway has experienced drastic visual changes over recent decades, which could soon be accentuated by climate change.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? Yarlung Zangbo River, Tibet Autonomous Region of China [29.2814054, 91.3256581]

What's in the photo? The braided branches of a river winding through the Tibetan Plateau

Which satellite took the photo? Landsat 9

When was it taken? Feb. 8, 2025

This striking satellite photo shows a particularly convoluted section of a record-breaking "braided river" in China, which drastically changes shape every year and could become more unstable over the coming decades due to climate change.

The Yarlung Zangbo River is a roughly 1,250-mile-long (2,000 kilometers) waterway that stretches from its origin at a glacier in the eastern Tibetan Plateau all the way into India. It is the longest river in Tibet, as well as the fifth longest in China, and holds the record for being the highest major river on Earth, flowing at an average elevation of 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) above sea level, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

The photographed section of the river is located in Zhanang County, just before it passes through the world's deepest land-based canyon and its namesake, the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, which is more than 6,000 meters (20,000 feet) deep — or three times deeper than Arizona's Grand Canyon.

Yarlung Zangbo is a classic example of a braided river — a waterway with "multi-threaded channels that branch and merge to create the characteristic braided pattern," with mid-channel sandbars that are "formed, consumed, and re-formed continuously," according to the National Park Service.

This section is where the most braiding occurs anywhere along the river, with up to 20 channels across at certain points in the image.

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

Yarlang Zangbo's extreme braiding is caused by heavy sediment deposits from the steep slopes of the adjacent Himalayas, which are washed into the river and help carve new channels into the ground, Zoltán Sylvester, a geologist at the University of Texas at Austin, told the Earth Observatory. The river changes shape so often that no vegetation can fully grow on the sandbars that sporadically appear between the river's braids, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You can see how quickly the river changes shape for yourself in a 37-year timelapse animation, which shows annual satellite images of this spot taken between 1988 to 2025 by Landsat 5, Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 (see below).

Eagle-eyed viewers may also be able to spot a narrow bridge, which was constructed over the shapeshifting waterway in 2014. (It's visible as a thin line near the far right-hand side of the animation).

The river starts at the Angsi Glacier, emerging from a stream of meltwater that flows from the ice mass. However, this was only officially confirmed in 2011, according to Chinese state media. Before this, there was confusion among scientists about whether the river actually originated from a meltwater stream coming from the nearby Chemayungdung Glacier.

Like many other Himalayan ice masses, the Angsi Glacier has lost a significant amount of water in recent decades due to human-caused climate change. The resulting meltwater has caused more sediment to be deposited into the river, which can increase erosion and make it more likely for its banks to collapse. According to a 2024 study that analyzed satellite photos of the 13 major rivers in the Tibetan Plateau, this poses a risk to local ecosystems, infrastructure and landscape stability.

When the river eventually reaches India, it becomes part of the Brahmaputra River and continues for another 1,800 miles (2,900 km) until it reaches the Ganges River Delta, where it drains into the Indian Ocean, according to the Earth Observatory.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus