Glaciers across North America and Europe have lost an 'unprecedented' amount of ice in the past 4 years

Glaciers in Washington, Montana, British Columbia, Alberta and the Swiss Alps have set grim records over the past four years, with both the annual amount of ice lost and the four-year average reaching all-time highs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

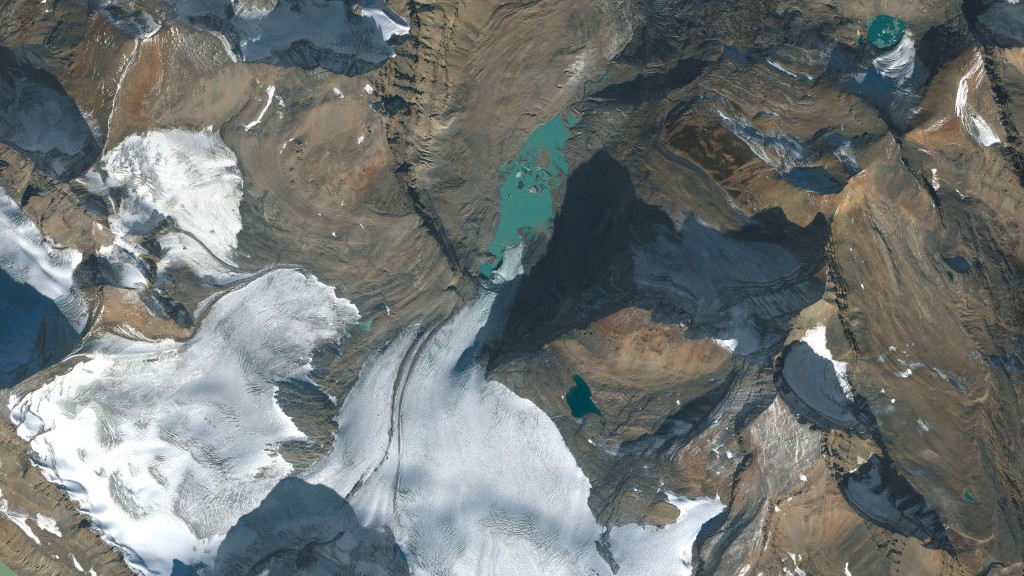

Glaciers in Washington, Montana, British Columbia, Alberta and the Swiss Alps lost an unprecedented amount of ice between 2021 and 2024, a new study reveals.

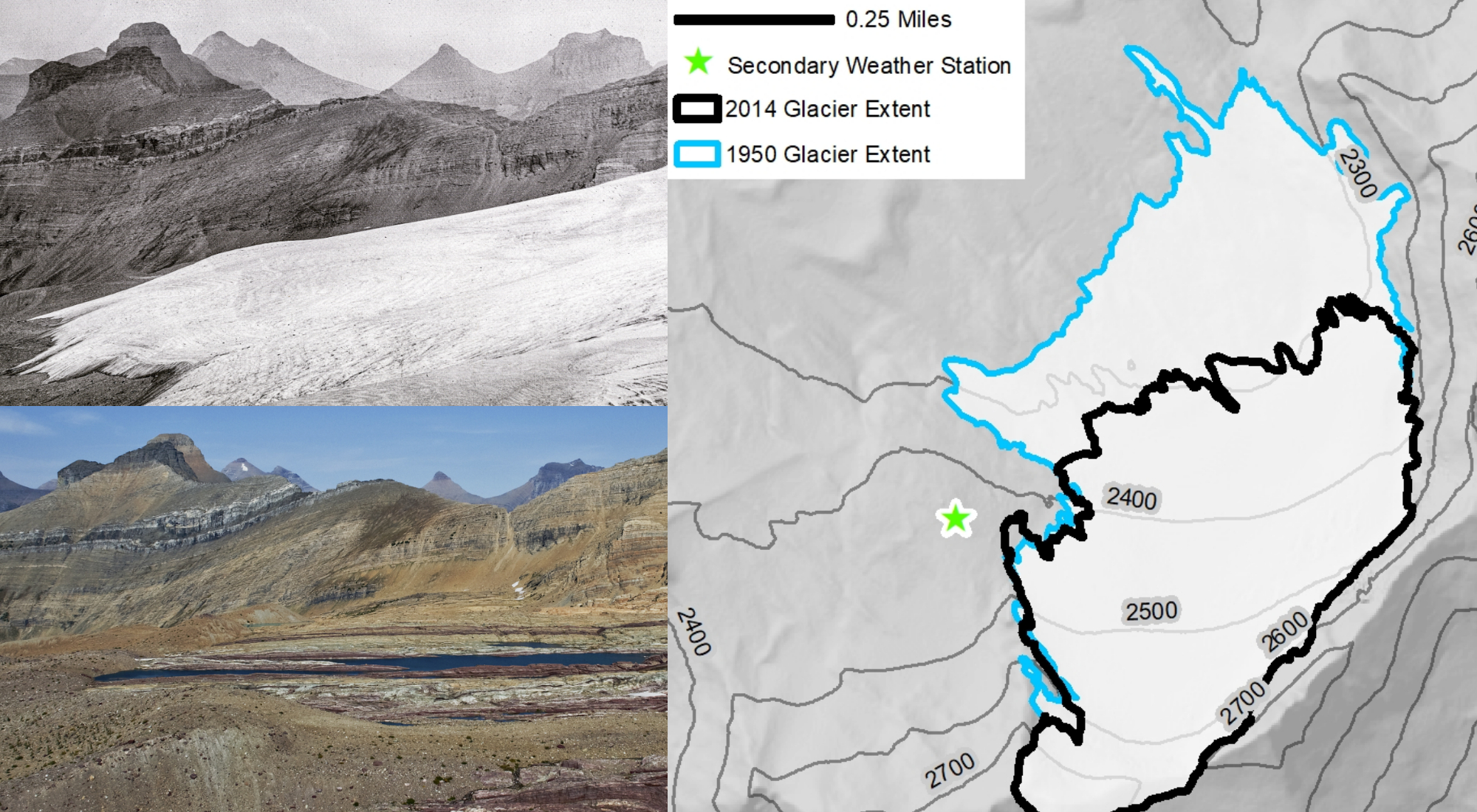

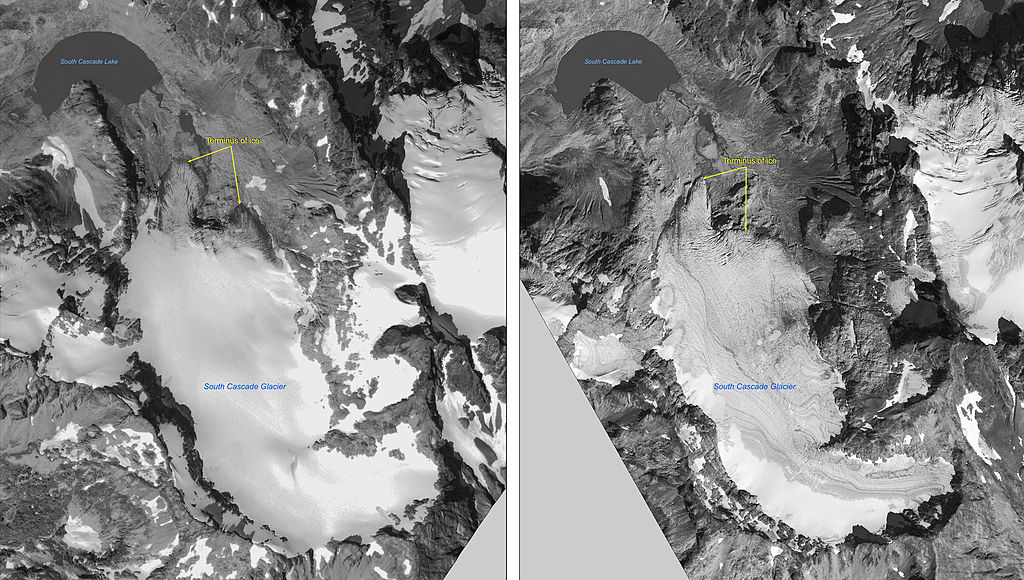

The cumulative loss in these four years was double that recorded between 2010 and 2020, shrinking glaciers by up to 13%, researchers found. Glaciers in the U.S. and Canada lost 24.5 billion tons (22.2 billion metric tons) of ice per year on average, while glaciers in the Swiss Alps lost 1.7 billion tons (1.5 billion metric tons) of ice per year.

"Previous records were shattered," study co-author Matthias Huss, a lecturer in the Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, told Live Science in an email. "We knew that these extreme glacier melt rates would come up. Nevertheless, the day you go out and witness these results based on the measurements, it is still surprising and difficult to accept."

The studied glaciers are located in regions where there is "very good, almost real-time, observational coverage," Huss said. The yearly losses of ice from these glaciers between 2021 and 2024, as well as the total loss of ice measured during this period, are record-breaking.

"Meteorological conditions that favored high rates of mass loss included low winter snow accumulation, early-season heat waves, and prolonged warm, dry conditions," the researchers wrote in the new study, published June 25 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Between 2000 and 2023, glaciers around the world collectively lost 301 billion tons (273 billion metric tons) of ice per year, contributing to around one-fifth of observed sea-level rise, according to the study. The aim of the new research was to determine whether the past four years of glacier melt stood out from previous years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found that 2021 to 2024 was the worst period for ice loss since glacier monitoring began in the 1960s. Glacier ice loss was extreme over the four-year period, with one-tenth of all glacier ice in Switzerland melting away in just two years between 2022 and 2023, Huss said.

"It is interesting but also alerting to see that these extremes are widespread and do not occur only in a single region but globally, even though the exact timing of the most important melt years is often not the same," he said.

Glacier ice loss not only exacerbates sea level rise but also threatens freshwater availability, elevates the risk of geohazards and drastically alters mountain landscapes, according to the study.

Heat waves and wildfires

To examine glacier melt, the team used data from the World Glacier Monitoring Service and airborne surveys, as well as climate records and satellite observations. They fed this information into a computer model to evaluate mass changes for two U.S. glaciers, three Canadian glaciers and five Swiss glaciers. The two U.S. glaciers were the South Cascade Glacier in Washington state and the Sperry Glacier in Montana. The three Canadian glaciers were the Place, Peyto and Helm glaciers.

Both in North America and Switzerland, one of the biggest factors driving glacier melt was extremely high summer temperatures. A heat wave in June 2021 in the U.S. and western Canada resulted in huge snowpack losses, and another heat wave in 2023 caused an early start to the wildfire season, which indirectly affected glaciers through soot particles that darkened the ice.

Darker surfaces from soot and other impurities absorb more radiation from the sun than light surfaces do, leading to more melt. More melt exposes vegetation, which is even darker than darkened ice and, therefore, leads to more heat absorption. This additional heat absorption on Earth's surface gradually contributes to global warming, as the heat is no longer reflected back out to space, which, in turn, leads to more wildfires and more soot deposition.

Another important factor driving glacier melt was the loss of firn zones, which are areas where snow has not yet been compressed into ice. The snow in these zones has a granular texture that helps to retain meltwater and prevent runoff, and it also reflects more sunlight back out to space than ice does, according to the study.

Computer models of glaciers do not currently account for firn zones and the influence of soot and other impurities. The effects of extreme weather events, such as wildfires and heat waves, should also be considered, the study authors argued.

Peak glacier ice loss

The study also found that ice loss from glaciers may have peaked between 2021 and 2024, raising serious concerns about water management in some regions, Huss said.

"It is not that melting will decline in the future with additional warming but the huge losses have resulted in rapidly shrinking ice cover and in some regions even a complete disappearance of small glaciers," he said.

This means that glaciers may now release less water into rivers and streams than they did up until 2024, even if global temperatures keep increasing. Communities, agriculture and industries that rely on glacier meltwater may therefore see their supply dwindle in the coming years.

The results are alarming and "clearly fit the global trend," Huss said. However, it's important to note that "we are highlighting two regions [western U.S.-Canada and the Swiss Alps] with absolutely exceptional changes in single years that will not immediately be reflected in all regions," he said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus