300,000-year-old teeth from China may be evidence that humans and Homo erectus interbred, according to new study

A study of a handful of 300,000-year-old teeth revealed an ancient human group had a mix of archaic and modern tooth features.

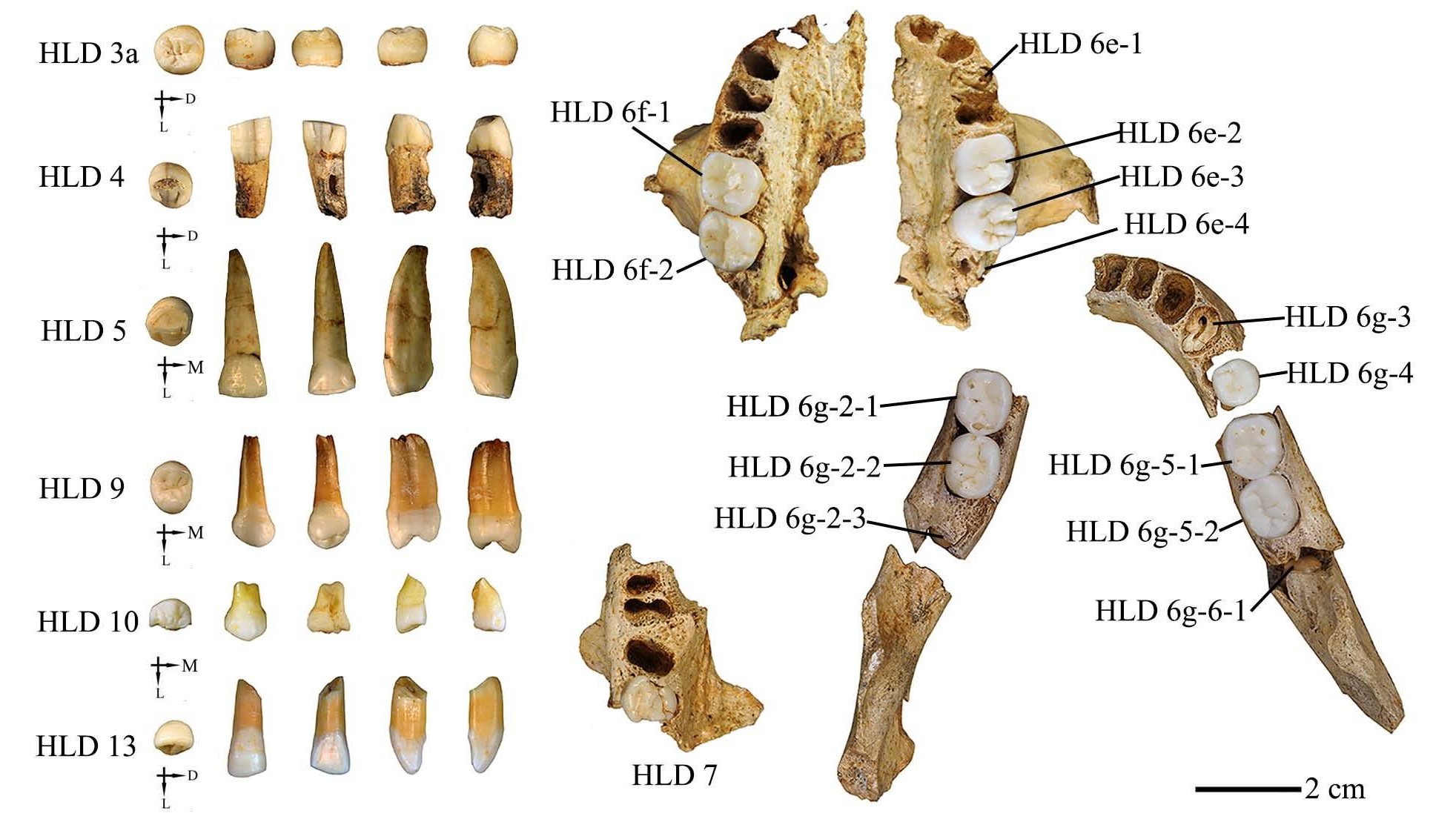

A small collection of 21 teeth may have big implications for the evolution of humans in Asia. The dentition, which comes from a mystery human ancestor that lived at least 300,000 years ago in China, shows an unusual combination of features that may suggest early humans interbred with Homo erectus, a new study reveals.

"It's a mosaic of … traits never seen before — almost as if the evolutionary clock were ticking at different speeds in different parts of the body," study co-author María Martinón-Torres, a paleoanthropologist at the Spanish National Research Center for Human Evolution (CENIEH), said in a statement.

In a study published in the September issue of the Journal of Human Evolution, researchers studied a handful of teeth from the Hualongdong archaeological site in South China and found that they had a mixture of ancient and modern traits.

The teeth belonged to the Hualongdong people, a mysterious group of hominins discovered in 2006. They lived during the Middle Pleistocene epoch around 300,000 years ago. Researchers have found at least 16 individuals to date.

An early analysis of the skeletons suggested they might have been a form of East Asian H. erectus, which reached China by 1.7 million years ago. But a more recent analysis showed that the bones and teeth of the Hualongdong people had a mix of traits typically seen in Homo sapiens and H. erectus. Specifically, Hualongdong people had facial features more similar to humans but limb proportions more often seen in H. erectus.

The new study similarly revealed a mix of traits in the teeth of the Hualongdong people. Most of the dental features appeared modern, including the small size of the wisdom teeth. But the roots of the molars were quite thick and robust, more similar to those found in H. erectus.

Related: Ancient 'Dragon Man' skull from China isn't what we thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers aren't sure why the Hualongdong teeth look like this, since paleoanthropologists are still piecing together the evolutionary history of humans in China, but they suggested several ideas in the study.

One possible explanation is that the Hualongdong population was closely related to H. sapiens but distinct from Neanderthals and Denisovans, both archaic populations of humans that interbred with some of our ancestors.

Another possibility is that the bones and teeth of the Hualongdong people "could be the result of genetic drift or gene flow with a more archaic form, such as Homo erectus," the researchers wrote in the study. Essentially, the Hualongdong population could be the result of H. erectus and humans having babies or could have come about because of another change in their genetic makeup.

Human ancestors from the Middle Pleistocene epoch are being discovered and analyzed at a rapid pace, paving the way for a better understanding of human origins in Asia.

In 2019, the diminutive species Homo luzonensis was found in the Philippines; in 2021, a newfound species called H. longi was identified in northern China (although the specimen was later found to be a Denisovan); and in 2024, the discovery of Homo juluensis from China was announced. All of these newly identified species of ancient humans date to around 300,000 to 150,000 years ago, and paleoanthropologists are only just beginning to understand how they are all related.

"The Hualongdong discovery reminds us that human evolution was neither linear nor uniform, and that Asia hosted multiple evolutionary experiments with unique anatomical outcomes," study co-author José María Bermúdez de Castro, a paleobiologist at CENIEH, said in the statement.

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus