Neanderthal genes may explain disorder where brain bulges out of the skull

Neanderthal genes may explain why some people have Chiari malformation type I, a condition in which the brain bulges out of the back of the skull.

Neanderthals that interbred with our ancestors may have passed on DNA that causes some people to develop a potentially fatal condition where the brain bulges out of the skull, a new study finds.

The disorder, known as Chiari malformation type I, affects the lower part of the cerebellum, the part of the brain that helps control motions. In people with this condition, the cerebellum protrudes through the hole at the base of the skull and into the spine. Symptoms may include headaches, neck pain and dizziness, and if too much of the brain bulges out, it can be fatal.

In mild cases, the symptoms may be treated with muscle relaxants, whereas in severe cases, doctors may treat the condition by removing chunks of bone from the braincase or vertebra, Mark Collard, a paleoanthropologist at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, told Live Science.

Discovered in the 1800s by Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari, the disorder is thought to affect about 1 in 1,000 people. However, recent imaging research suggests it may be significantly more common, potentially occurring in more than 1 in 100 people — it's just that most cases escape notice because they do not manifest major symptoms, Collard said.

Chiari malformation type 1 happens when the occipital bone at the back of a person's skull is not big enough to hold the brain properly, leading the bulging portion to become pinched. However, it remains uncertain what causes the occipital bone to be unusually small.

In a 2013 study, scientists proposed that the condition was the consequence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans in Eurasia. Previous research found such intermixing led the genomes of all non-Africans to contain 1.5% to 2% Neanderthal DNA.

Related: 'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

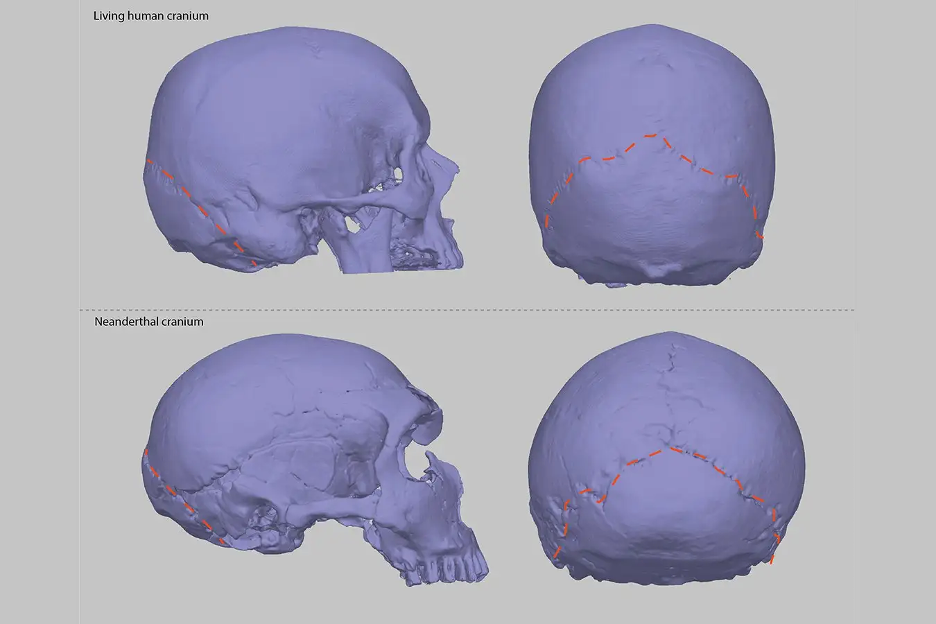

Modern human skulls are globular, with a rounded back of the skull, whereas Neanderthal skulls were relatively elongated, with a more angular back of the skull. The 2013 study suggested Neanderthal DNA might influence modern human skull development, leading to a mismatch between the size and shape of the brain and the skull — especially the base of the skull.

To explore this idea, the new study examined 3D CT scans of the skulls of 103 living people — 46 with the disorder, and 57 without. The researchers compared these skulls with eight fossil skulls of close relatives of modern humans, including Neanderthals, Homo heidelbergensis, Homo erectus and prehistoric Homo sapiens.

Study lead author Kimberly Plomp, an osteologist at the University of the Philippines Diliman, and her colleagues found that the skulls of modern humans with the disorder were more similar in shape to Neanderthals than people without the malformation. All other fossil skulls were more similar to modern humans without the disorder.

"Our study may mean we are one step closer to obtaining a clear understanding of the causal chain that gives rise to Chiari malformation type 1," said Collard, a co-author on the study. "In medicine, as in other sciences, clarifying causal chains is important. The clearer one can be about the chain of causation resulting in a medical condition, the more likely one is to be able to manage, or even resolve, the condition."

Collard stressed these findings do not definitively prove a link between this disorder and Neanderthal genes. "Scientific research is rarely, if ever, conclusively based on a single study," he noted.

Future work could analyze more skulls, especially fossil ones, Collard said. Researchers can also focus on collecting data from Africa. "What we know about the occurrence of Neanderthal DNA in the living human gene pool suggests that we should expect higher prevalence of Chiari malformation type 1 in Europe and Asia than in Africa," Collard said.

If future research does confirm a link between Neanderthal genes and this disorder, "then it might make sense to add screening for such genes to early childhood health assessments," Collard said. That way, individuals with a higher-than-average risk of developing Chiari malformation type 1 could be identified and then monitored and managed by health professionals.

The scientists detailed their findings June 27 in the journal Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health.

Neanderthal quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus