Bite marks reveal giant terror birds were potentially prey for another apex predator — humongous caiman

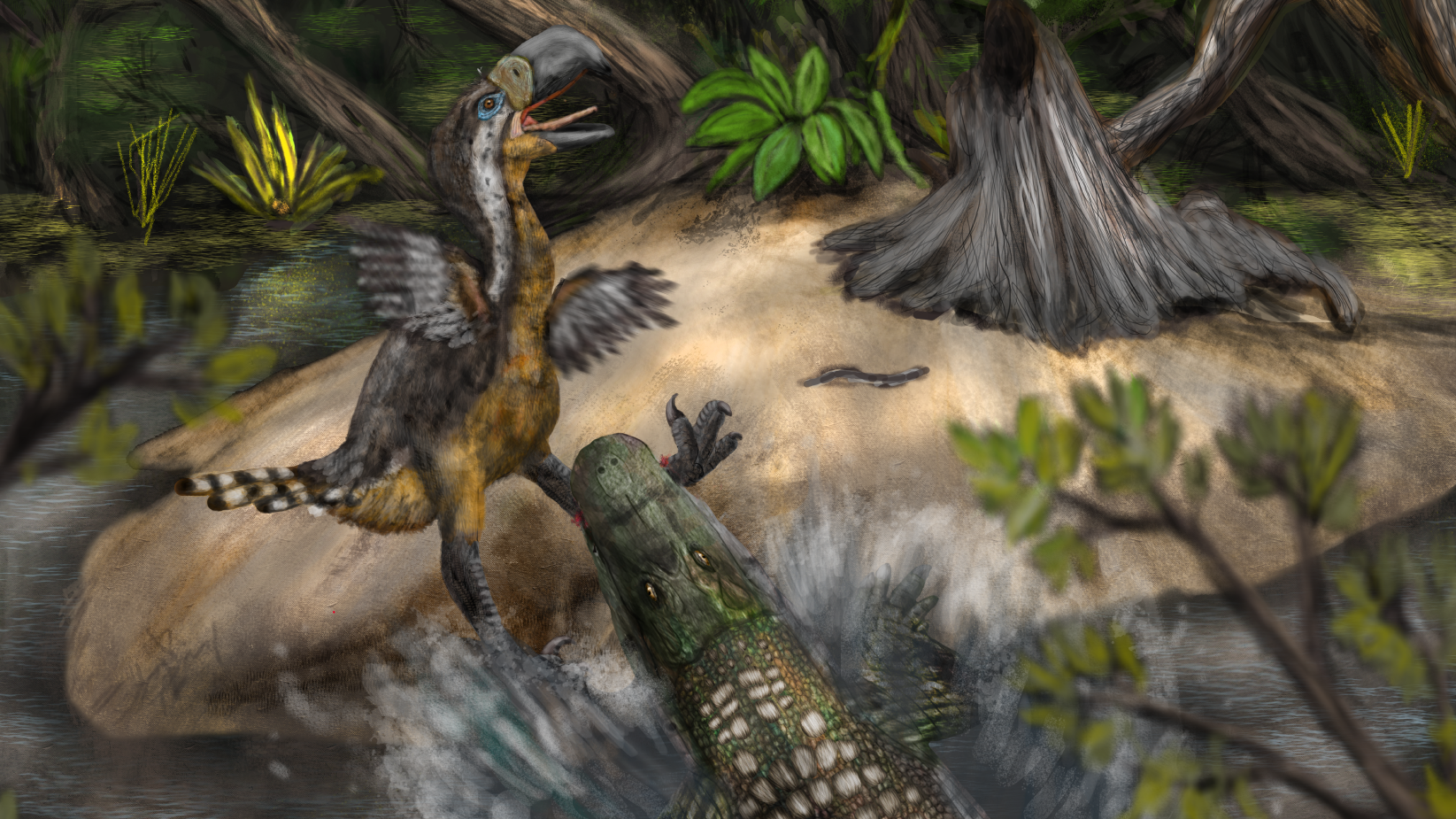

Researchers have found evidence of a titanic tussle between a terror bird and a large caiman in Colombia's ancient La Venta wetlands.

Fossilized bite marks suggest there could have been a dramatic tussle between a gigantic terror bird and an even more massive crocodile around 12 million years ago.

Phorusrhacids, commonly known as "terror birds," were apex predators that terrorized prey in the ancient ecosystems of South America. While these flightless carnivores had little to fear on land, a new study, published Tuesday (July 22) in the journal Biology Letters, indicates that they weren't necessarily safe around water.

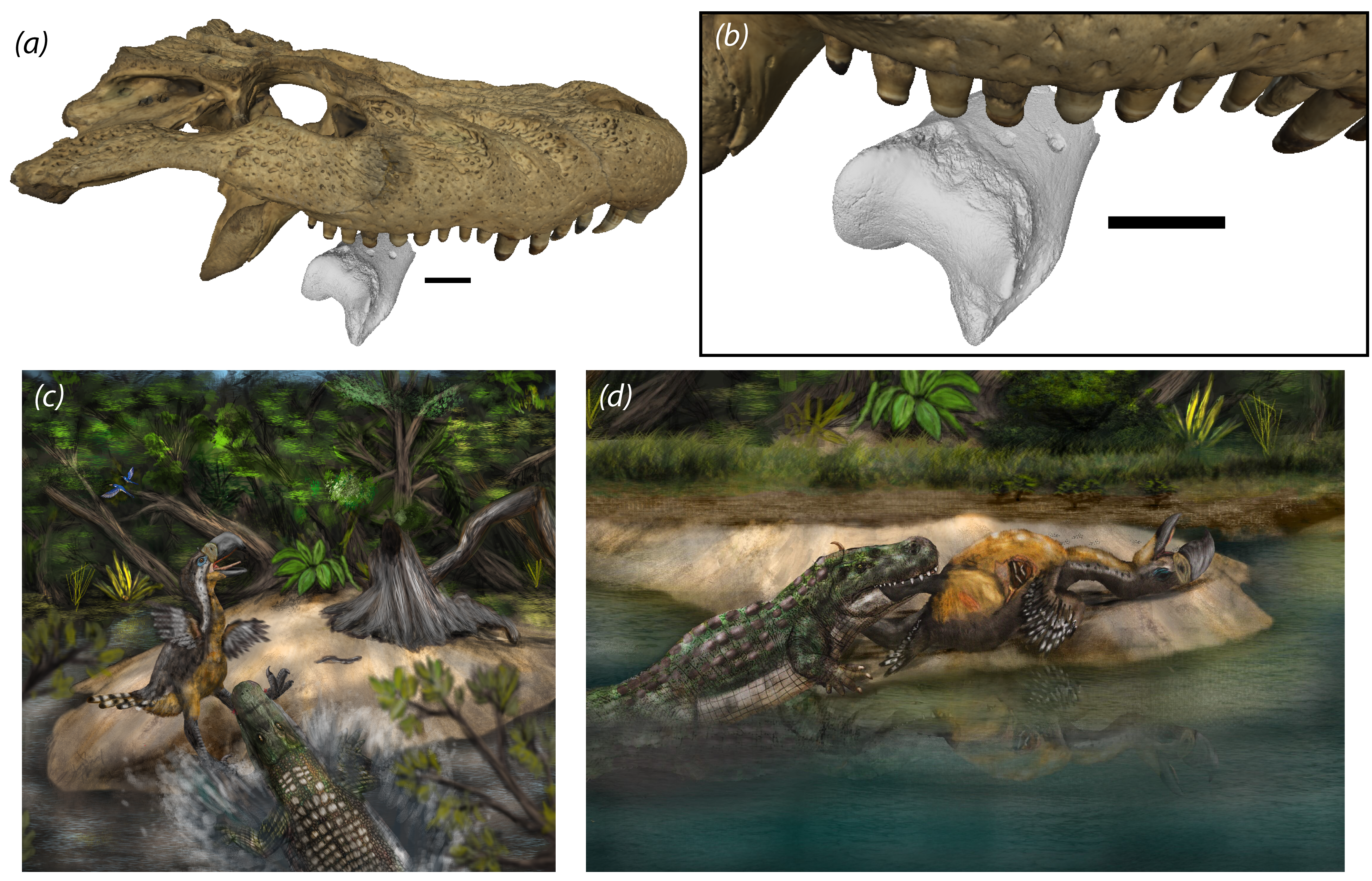

Researchers analyzed tooth marks on the leg bone of one of the largest terror birds ever discovered — estimated to have stood more than 9 feet (2.7 meters) tall — unearthed at the La Venta fossil site in Colombia. The team concluded that a 15-foot-long (4.7 meter) caiman was likely responsible for the marks.

"We have learned that terror birds could also be preyed [upon] and that even being an apex predator has risks," study lead author Andrés Link, a paleontologist and biologist at the University of the Andes in Colombia, told Live Science in an email.

The study doesn't rule out the possibility that the terror bird simply died near a body of water and was subsequently munched on by the caiman, making it a case of scavenging rather than hunting.

Researchers first unveiled the terror bird fossil in a study published last year. The study's authors said at the time they suspected a crocodilian killed the bird, but they hadn't yet published an analysis of the four tooth marks found on the bone.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, the researchers evaluated the bite mark by creating detailed 3D images of the fossil. The bone marks had no signs of healing, while the size and shape of the marks were consistent with those delivered by a caiman that was around 15.1 to 15.8 feet (4.6 to 4.8 m) long, according to the study.

The team hypothesized that La Venta's largest ancient caiman species, Purussaurus neivensis, was behind the bite. However, the individual responsible would have been a subadult, and not yet fully grown. Link told Live Science that P. neivensis could grow up to around 33 feet (10 m) long. "It was a massive animal!" he said.

Without direct evidence of the caiman eating the terror bird, the findings represent an anecdotal account of an aquatic apex predator feeding on a land apex predator during the middle of the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5 million years ago).

"In my opinion this study contributes to understanding the diet of Purussaurus, the landscape of fear near the water bodies [at] La Venta during the middle Miocene and the complex ecological interactions in the protoAmazonian ecosystems of [tropical] South America," Link said.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus