Meet 'Dragon prince' — the newly discovered T. rex relative that roamed Mongolia 86 million years ago

A new species of dinosaur that was probably a princely ancestor of T. rex, the king of the dinosaurs, has been identified from fossils excavated in Mongolia.

Scientists have identified a never-before-seen species of dinosaur called the dragon prince — a prehistoric predator that set tyrannosaurs on the path to ruling Earth. This newly discovered relative of Tyrannosaurus rex came to light after researchers re-examined fossils found in Mongolia.

Its existence sheds light on the story of tyrannosaur dinosaurs and how they evolved and spread.

The scientists named the dinosaur the dragon prince of Mongolia (Khankhuuluu mongoliensis), with the genus name based on the Latinization of the Mongolian words for prince and dragon. Their findings were published Wednesday (June 11) in the journal Nature.

"They [tyrannosauroids] were the princes before they took the mantle of kingship," study co-author Jared Voris, a researcher at the University of Calgary in Canada, told Live Science.

Tyrannosauroids were giant apex predators that walked on two legs, had huge heads with sharp teeth and tiny arms. They are part of the larger tyrannosauroid family and were thought to have evolved from smaller species — but until now there has been little fossil evidence to support this idea.

So, Voris set out for Mongolia to examine partial tyrannosauroid skeletons that had been excavated decades ago but not yet fully examined.

Related: Dinosaurs might still roam Earth if it weren't for the asteroid, study suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Many of us in the palaeontology community knew that these Mongolian fossils were lurking in museum drawers, waiting to be studied properly, and apt to tell their own important part of the tyrannosaur story," Steve Brusatte, a palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Edinburgh, U.K., who wasn't involved in the research, told Live Science.

The specimens that really caught Voris' eye were found in Mongolia in 1972 and 1973 and described in a scientific paper in 1977, when the individuals were identified as the already known genus Alectrosaurus.

But after being reexamined, "I realized it was something completely different than anything we'd ever seen," Voris said. "And it actually represented the ancestor of all of our big apex predatory tyrannosaurs that we find both here in Alberta and in Mongolia and China."

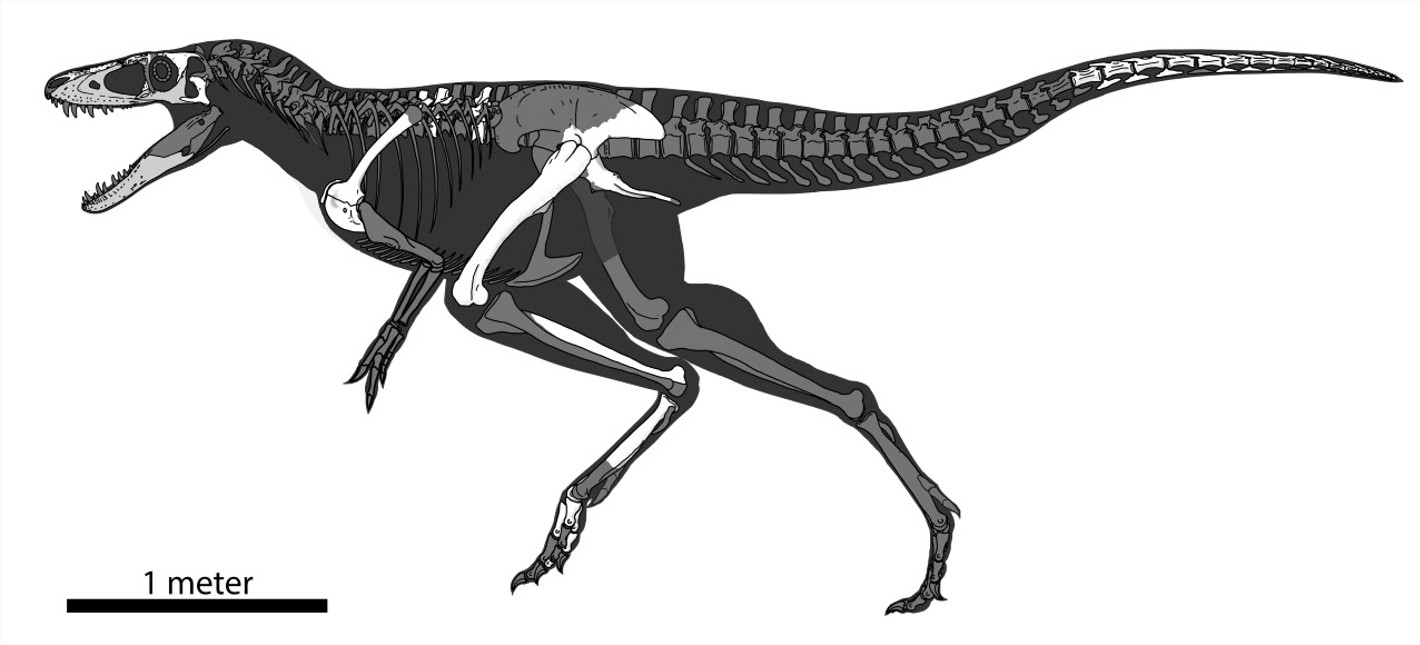

The dragon prince lived 86 million years ago and looked much like a tyrannosaur, but it was only about 13 feet (4 meters) long, weighing in at 1,650 pounds (750 kilograms). Many later tyrannosaurs were much bigger, with T. rex reaching 41 feet (12.5 m) long and weighing up to about 23,000 pounds (10,400 kg). The dragon prince also had a smaller head and longer arms compared to later tyrannosaurs.

"It's a nice new discovery giving us a better sense of what this intermediate phase of tyrannosaur history is like," Thomas Holtz, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Maryland, who wasn't part of the team, told Live Science.

Voris thinks the specimens are small adult individuals, rather than young dinosaurs. He identified a slew of features that are indicators of maturity, including fused-up vertebrae, prominently developed small horns and the nasal bone having a wrinkled texture. "The size is representative of the actual species rather than it being a younger animal," Voris said.

However, until a cross-section of the bones is done to look at growth rings, which hasn't yet been permitted because of the rare status of the fossils, we can't be sure of this adult status, Holtz said.

Unlike later tyrannosaurs, K. mongoliensis probably didn't hunt sauropods, the huge herbivorous dinosaurs with the long necks and long tails, said study co-author Darla Zelenitsky, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary. "It was probably taking down prey smaller than itself," Zelenitsky told Live Science.

The finding suggests that tyrannosauroids were still small at the time, and only later became giants.

"What makes the specimens so important is their age. They are about 86 million years old, a good 20 million years older than T. rex," Brusatte said. "It shows that tyrannosaurs were still relatively small at this time, and only later did they become colossal."

The researchers also compared 12 species of tyrannosaurs to figure out when and where they lived, how they were related, and when any migrations might have taken place.

They found that, about 85 million years ago, K. mongoliensis, or a closely related species, migrated out of Asia into North America across a land bridge where the Bering Strait is now and gave rise to the first true tyrannosaurs. These went on to be the dominant predators in North America in the latter part of the Cretaceous period between about 85 million and 66 million years ago.

But about 78 million years ago, a tyrannosaur migrated back across the land bridge, resulting in their first appearance in Asia.

This resulted in the evolution of two tyrannosaur subgroups in Asia: huge ones weighing several tons like Tarbosaurus bataar, and smaller, slim ones such as Qianzhousaurus sinensis, which was nicknamed "Pinocchio rex" because of its small size and long snout.

During a third migration, about 68 million years ago, one of the giant tyrannosaur species from Asia traveled back to North America and probably gave rise to T. rex, Zelenitsky said.

"They show that a few big migration events back and forth between Asia and North America were the drivers of much of tyrannosaur evolution," Brusatte said. "The tyrannosaur family tree was shaped by migration, just like so many of our human families."

Chris Simms is a freelance journalist who previously worked at New Scientist for more than 10 years, in roles including chief subeditor and assistant news editor. He was also a senior subeditor at Nature and has a degree in zoology from Queen Mary University of London. In recent years, he has written numerous articles for New Scientist and in 2018 was shortlisted for Best Newcomer at the Association of British Science Writers awards.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus