Ancient 'Dragon Man' skull from China isn't what we thought

Scientists have determined that a giant skull from an ancient human relative named the "Dragon Man" is actually Denisovan.

Using cutting-edge DNA analysis, scientists have uncovered the true identity of an ancient human relative nicknamed the "Dragon Man."

The mystery began with a giant, human-like skull discovered by a Chinese laborer in Harbin City, China, in 1933. In 2018, the man's family recovered the Harbin skull, which the laborer had buried in a well, and donated it to science. The enormous cranium features a long, low braincase and a massive brow ridge, along with a broad nose and big eyes. Based on the skull's unusual shape and size, experts gave it a new species name — Homo longi, or "Dragon Man" — in 2021.

But in the past several years, there has been intense debate about whether Dragon Man, who lived at least 146,000 years ago, is a separate species. Instead, some researchers have claimed that the Dragon Man skull may be from a group of ancient humans called the Denisovans, since no Denisovan skull had ever been found.

Now, in two studies published Wednesday (June 18) in the journals Science and Cell, researchers have proved that Dragon Man is indeed the face of Denisovans.

Scientists first attempted to retrieve an ancient genome from the bones and teeth of the Harbin skull, without success. But they were able to recover some DNA from plaque that had hardened on the teeth and some information on proteins from an inner ear bone.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is passed from mother to child, recovered from the skull showed that Dragon Man was related to an early Denisovan group that lived in Siberia from around 217,000 to 106,000 years ago, which means that Denisovans inhabited a large geographical range in Asia, the researchers wrote in the Cell study.

Additionally, the researchers investigated the skull's "proteome," the set of proteins and amino acids found in the skeleton. By comparing the proteome to those of contemporary humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans and nonhuman primates, the researchers found a clear connection between the Harbin cranium and early Denisovans, they wrote in the Science study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: 43,000-year-old human fingerprint is world's oldest — and made by a Neanderthal

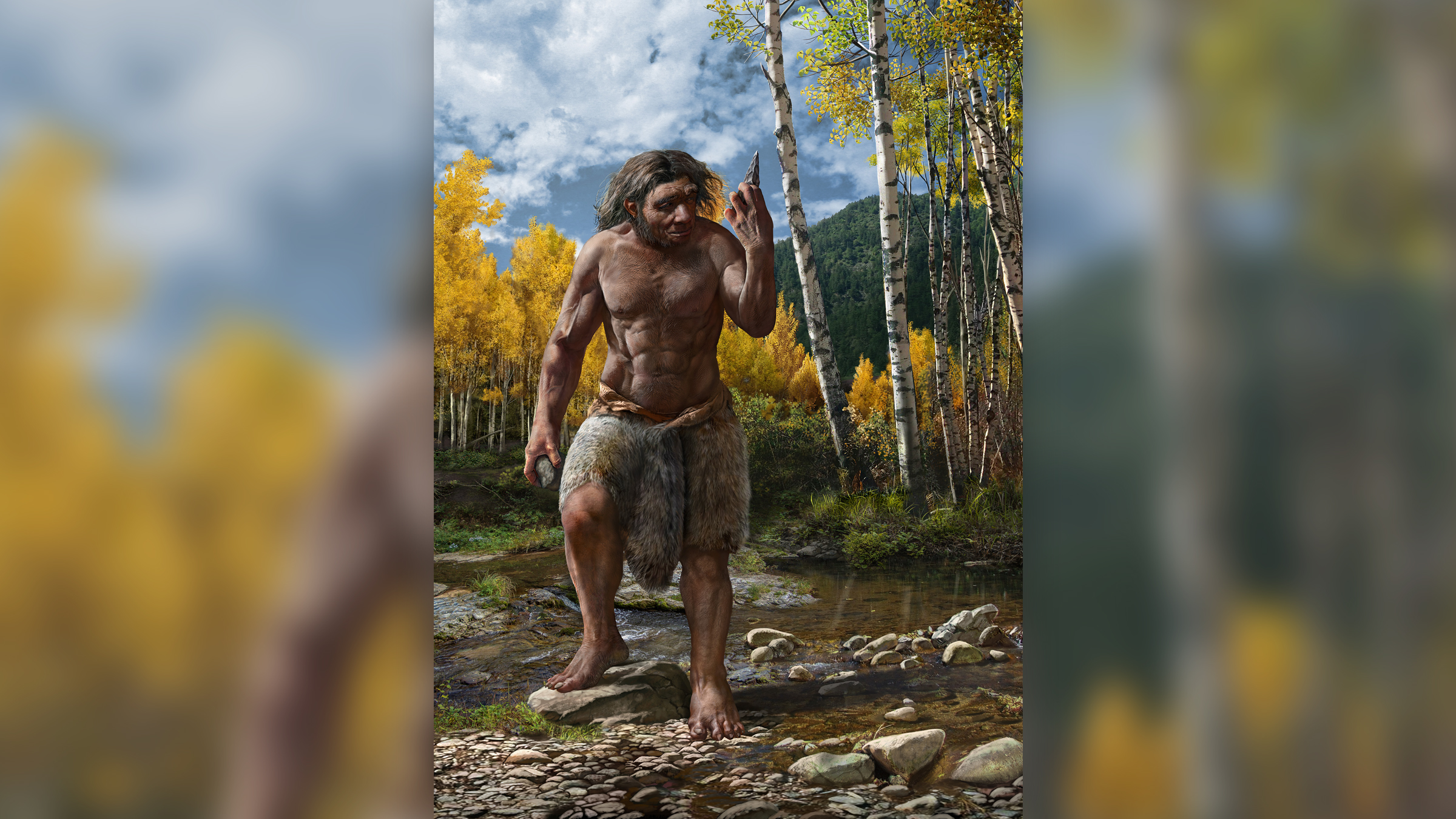

"We now have the first comprehensive morphological blueprint for Denisovan populations, helping to address an unresolved question that has persisted over the last decade on what Denisovans looked like," they wrote in the Science study. In short, Denisovans looked like Dragon Man.

While the mystery of the enormous skull has been largely resolved, experts still need to discuss its assignment to the H. longi species.

"This work makes it increasingly likely that Harbin is the most complete fossil of a Denisovan found so far," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who has worked on the Harbin cranium but was not involved in these new studies, told Live Science in an email. Stringer added that "Homo longi is the appropriate species name for this group," although at this point, the group is small.

But Harbin's new identification as a Denisovan also requires experts to reconsider what they thought they knew about the evolution of humans in Asia, particularly in the Middle Pleistocene epoch, around 789,000 to 126,000 years ago. During this period, Eurasia was home to at least three different hominins — humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans — that frequently mated with one another, giving rise to the "muddle in the middle" nickname for this confusing period of evolution.

Until now, the Denisovan group of early humans has been known mostly from their DNA and a tiny handful of fossils. This is in stark contrast to Neanderthals, whose skulls have been found throughout Europe and Western Asia for more than 150 years.

With the identification of the Harbin skull as Denisovan and the identification of a jawbone found off the coast of Taiwan as Denisovan in a study published in the journal Science in April, this means paleoanthropologists have definitive examples that other unknown skulls can be compared to.

Studies of the size and shape of Middle Pleistocene fossil skulls will remain crucial for testing relationships, Stringer said, particularly because DNA does not preserve well in most fossils, and these studies are important for identifying what Denisovans actually looked like. But "there is certainly much more to come from extractions of ancient DNA and proteomes from human fossils," Stringer said.

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus