78,000-year-old footprints from Neanderthal man, child and toddler discovered on beach in Portugal

A Neanderthal trackway discovered in Portugal shows how an adult male and two children hunted for food 78,000 years ago.

Just before the first COVID lockdown in March 2020, Carlos Neto de Carvalho and his wife, Yilu Zhang, were walking along Monte Clérigo beach in southern Portugal. As the geologist and geographer couple scrambled over rocky outcrops and an old collapsed cliff, they stumbled on a series of ancient Neanderthal footprints.

"It was early in the morning of a sunny day, with perfect light for checking tracks," Neto de Carvalho told Live Science in an email. But when they brought colleagues back to the site to take photos of the tracks, "we were almost trapped by the sudden rise of the tide and needed to swim and climb a 15-meter [49 feet] nearly vertical cliff with all our gear," Neto de Carvalho said.

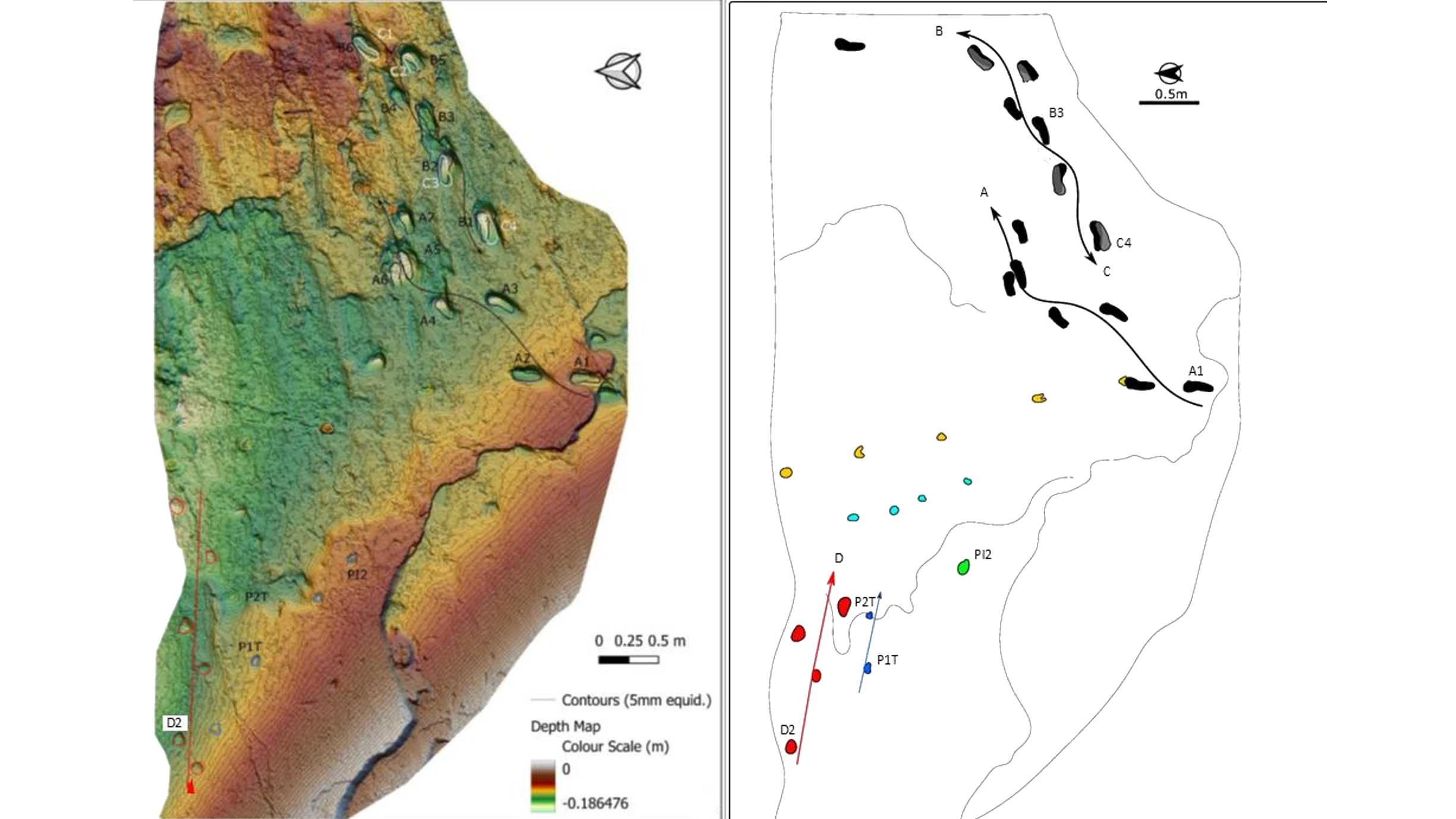

Their daring adventure paid off. The researchers ultimately discovered five trackways comprising 26 footprints at Monte Clérigo and, in turn, substantially increased experts' understanding of Neanderthals' activities along the Atlantic coast 78,000 years ago.

"The fossil record of hominin footprints, and especially the ones attributed to Neanderthals, is exceedingly rare," Neto de Carvalho and colleagues wrote in a study published July 3 in the journal Scientific Reports, since Neanderthal footprints are nearly identical to humans'.

In this case, the footprints were identified as Neanderthal because modern humans weren't in Europe at that time. Rather, evidence suggests that besides a few earlier failed attempts, Homo sapiens started leaving Africa around 50,000 years ago.

Only six sets of Neanderthal footprints had been discovered previously. Along with the Monte Clérigo tracks, the researchers have reported the new finding of a single footprint from Praia do Telheiro, also in southern Portugal, bringing the total number of Neanderthal trackways discovered in Europe to eight.

At Monte Clérigo, the ancient footprints were made near the shoreline in a coastal dune. Optically stimulated luminescence dating, which measures the last time a mineral was exposed to sunlight, placed the footprints in the range of 83,000 to 73,000 years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Based on the size and shape of the Monte Clérigo prints, the researchers think an adult Neanderthal male walked up and down the dune, accompanied by a child between 7 and 9 years old and a toddler under 2 years old.

"The fact that in the context of Monte Clérigo infant footprints were found together with those of older individuals suggests that children were present when adults performed day-to-day activities," the researchers wrote.

Because the trackways were heading both toward and away from the shore, these Neanderthals may have been foraging for food, such as shellfish. But another possibility is that the Neanderthals were practicing ambush hunting or stalking prey such as horses, deer or hares, according to the researchers, since some of the Neanderthal footprints were "overprinted" with large mammal tracks.

"At the Monte Clérigo site, the presence of footprints attributed to, at least, one male adult, one child and one toddler, negotiating the steep slope of a dune, allow us to speculate about close proximity to the campsite," the researchers wrote.

But if the Neanderthals had established a camp at Monte Clérigo, no evidence of it remains today.

"The presence of Neanderthals in these environments was intentional even if seasonal," the researchers wrote, "taking benefits from ambush hunting or stalking prey in a rugged dune landscape."

Neanderthal quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus