Astronomers discover new dwarf planet 'Ammonite' — and it could upend the existence of Planet Nine

A newly discovered dwarf planet called 'Ammonite' (2023 KQ14) has been spotted in the outer solar system, and it could be another nail in the coffin for the Planet Nine hypothesis.

Astronomers have discovered a possible new dwarf planet orbiting far beyond Pluto. First detected in March 2023 by Japan's Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, this object has been dubbed 2023 KQ14 and nicknamed Ammonite. Ammonite's appearance also puts a kink in what's known as the Planet Nine hypothesis, which suggests there may be an undiscovered ninth planet in our solar system.

Led by researchers in Japan, the team announced Ammonite's discovery in a paper published July 14 in the journal Nature Astronomy. The body gets its moniker from the fossil of a long-extinct cephalopod because it was identified as part of the survey project Formation of the Outer Solar System: An Icy Legacy, or FOSSIL.

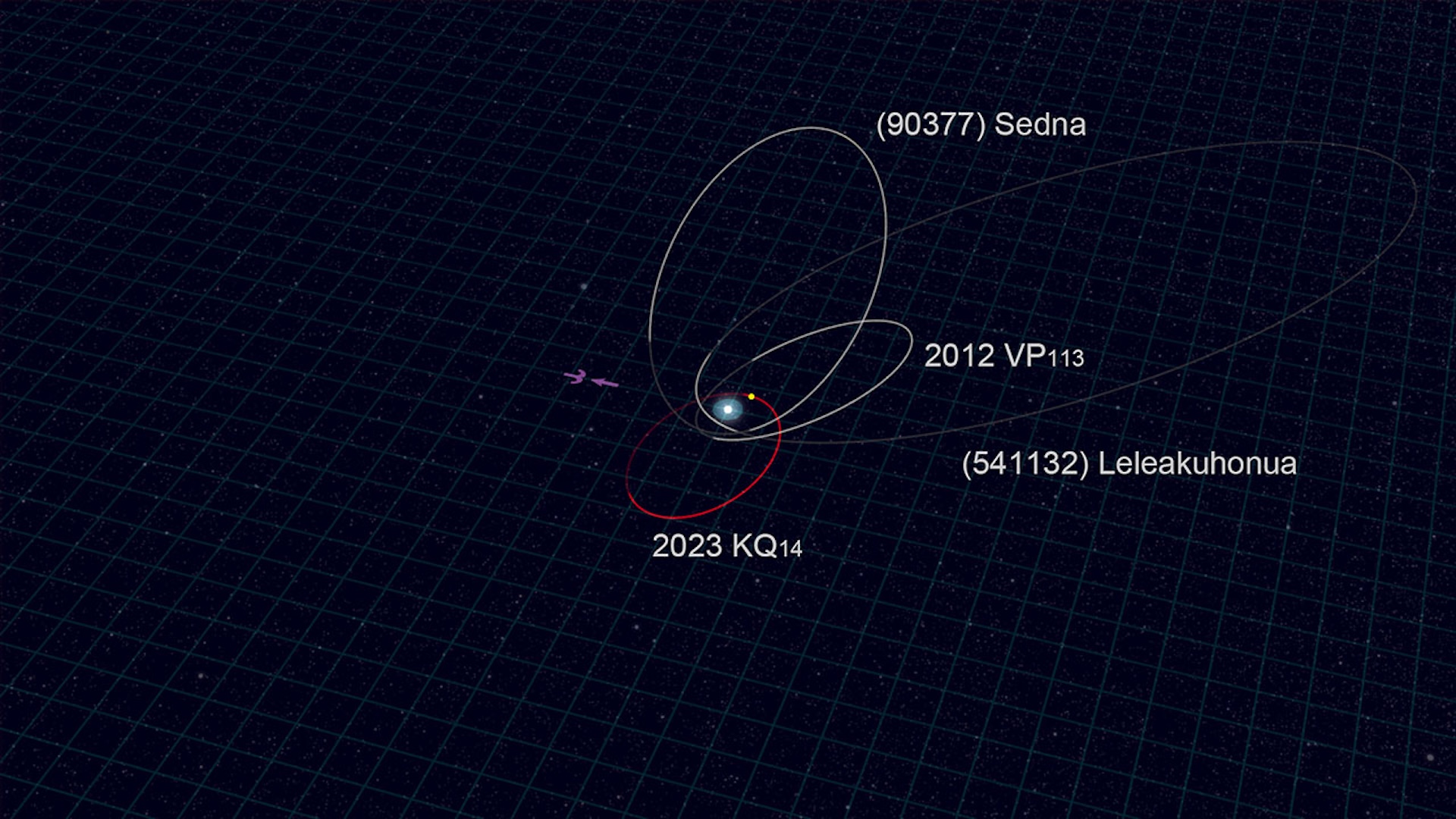

Ammonite is classified as a sednoid, which is an object beyond Neptune — our solar system's outermost confirmed planet — with a peculiar orbit. It's now the fourth sednoid discovered. The term "sednoid" comes from the dwarf planet Sedna, which exists at our solar system's edge and was discovered in 2004.

When describing the orbits of celestial bodies, astronomers use astronomical units (AU). The distance between Earth and the sun is approximately 1 AU. Following an elliptical path, Sedna is about 76 AU from the sun at its nearest point (perihelion) and 900 AU at its farthest (aphelion). Ammonite, meanwhile, is between 66 and 252 AU from the sun at the closest and farthest points in its orbit.

The discovery of 2023 KQ14 detracts from the possibility that there could be a ninth planet for our solar system, according to the study authors. First proposed in 2016, the Planet Nine hypothesis suggests there may be a Neptune-size planet orbiting the sun about 20 to 30 times farther from the sun than Neptune is.

This planet would explain the eccentric orbits of smaller bodies in the Kuiper Belt, which is the vast expanse of icy rocks that encompasses the outer solar system. It's believed that the gravity of a much more massive body, like a planet, may be shepherding these smaller objects. However, the relationship between the newest sednoid's orbit and that of the other three known sednoids calls this hypothesis into question.

"The planet 9 hypothesis is based on the fact that the known Sednoids have their orbit cluster on one side of the solar system," study co-author Shiang-Yu Wang, a research fellow at the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan, told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: What are dwarf planets — and how many are there?

Ammonite is unique among these sednoids because its orbit is on the opposite side — its furthest point from the sun is in the opposite direction from the other sednoids' furthest points. The fact that there is now a known object orbiting on this path decreases the possibility that a large planet could be out there, too.

"The fact that 2023 KQ14's current orbit does not align with those of the other three sednoids lowers the likelihood of the Planet Nine hypothesis," study co-author Yukun Huang, a project research fellow at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan's Center for Computational Astrophysics, said in a press release. "It is possible that a planet once existed in the Solar System but was later ejected, causing the unusual orbits we see today."

Other astronomers also believe Ammonite throws a wrench in this hypothesis. "The trouble is the evidence from the alignment has never been scientifically convincing and hasn't really grown stronger, even over the last 10 years or so," David Jewitt, a professor of astronomy at the University of California, Los Angeles who was not involved in Ammonite's discovery, told Live Science.

"Ammonite does not align with these six other objects, so weakens the case for Planet Nine, or means it must be very remote and correspondingly difficult to detect," Christopher Impey, an astronomy professor at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the sednoid's discovery, told Live Science.

But Impey is confident that, if there really is a Planet Nine, the newly activated Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile will soon be able to confirm it. "If Planet Nine exists, it will almost certainly be found in that survey data within a few years," he said.

Elana Spivack is a science writer based in New York City. She has a master's degree from New York University's Science Health and Environmental Reporting Program and a bachelor's from Kenyon College in Ohio. She's written for Inverse, Popular Science, BitchMedia and others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus