'We're bringing back avian dinosaurs': De-extinction company claims it will resurrect the giant moa in next 10 years

The South Island giant moa could be the next species that biotech company Colossal Biosciences "brings back" from extinction — but experts say the result will not and "cannot be" a moa.

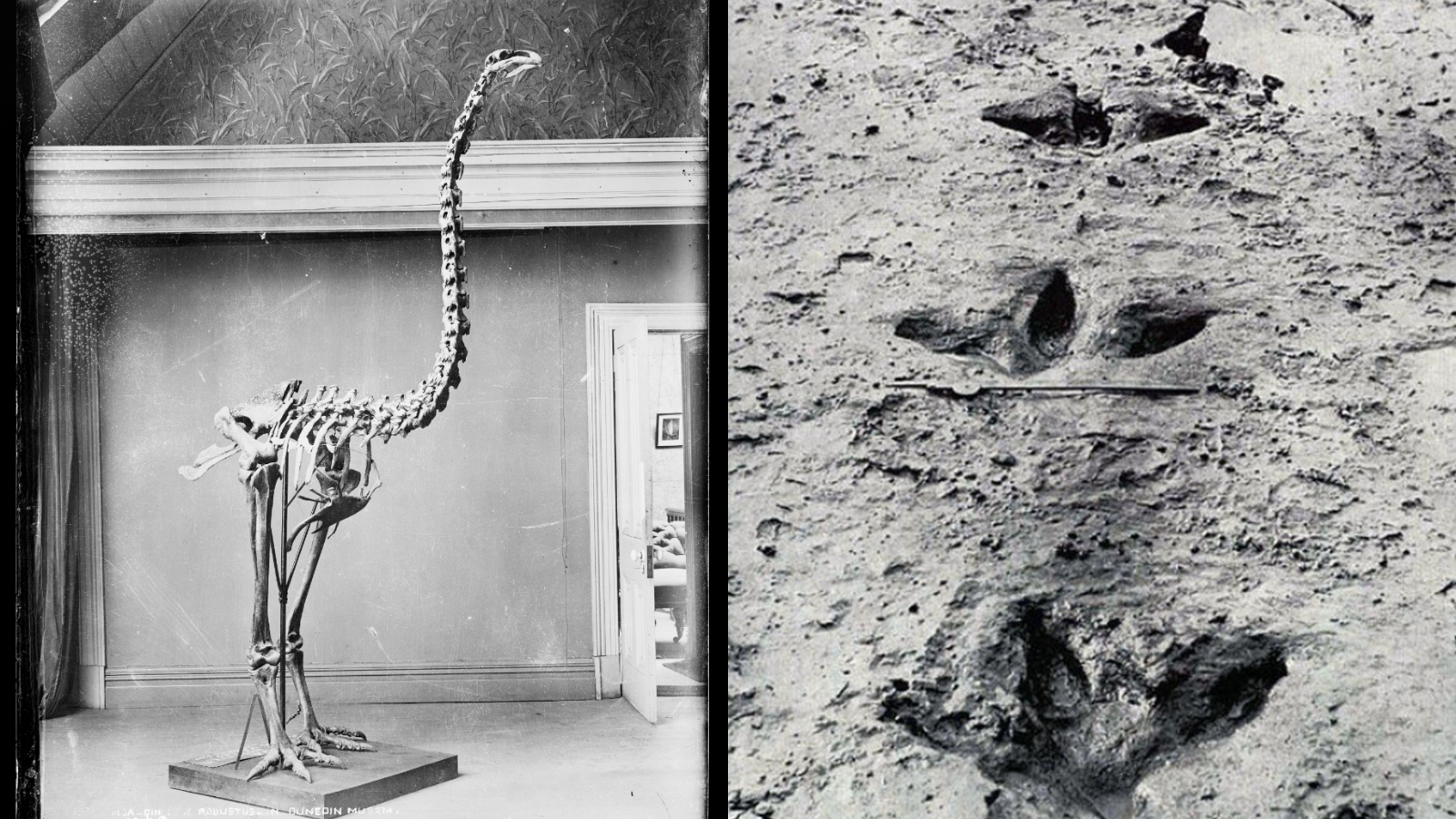

A giant, flightless bird that roamed New Zealand before going extinct about 600 years ago is the next species on a controversial list of "de-extinction" targets from the biotechnology company Colossal Biosciences.

Colossal announced on Tuesday (July 8) that its scientists and local Indigenous partners will "bring back" the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus) through genetic engineering within the next 10 years. D. robustus stood up to 12 feet (3.6 meters) tall and was the largest of nine known species of moa, all of which are thought to have gone extinct due to hunting by humans.

"We're bringing back avian dinosaurs," the company said in a post on Instagram.

A post shared by Colossal Biosciences (@colossal)

A photo posted by on

Colossal previously claimed to have brought back the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus), an ice age predator that went extinct more than 10,000 years ago — but the reveal in April drew criticism from many experts, who said the animals were merely gray wolves with a few, cherry-picked dire wolf traits. Colossal also has plans to "resurrect" the woolly mammoth, the dodo and the thylacine (a wolf-like creature also known as the Tasmanian tiger), but these projects are similarly shrouded in controversy.

"We have numerous taxa going extinct now so it is unacceptable that this is seen as okay just because it may be possible to regenerate an animal in the future," Trevor Worthy, a vertebrate paleontologist and associate professor at Flinders University in Australia who is not associated with Colossal, told Live Science in an email.

Colossal's new announcement immediately attracted criticism from researchers, who denounced the company's failure to acknowledge that the bird it will eventually create will not be a moa, but rather a hybrid with moa-like characteristics.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There is no current genetic engineering pathway that can truly restore a lost species, especially one missing from its ecological and evolutionary context for hundreds of years," Philip Seddon, a professor of zoology at the University of Otago in New Zealand, told the country's Science Media Center (NZSMC). "Any end result will not, cannot be, a moa — a unique treasure created through millennia of adaptation and change."

Following the dire wolf announcement, Colossal's chief scientist Beth Shapiro clarified in an interview with New Scientist that the animals are actually "gray wolves with 20 edits" and that "it's not possible to bring something back that is identical to a species that used to be alive." Shapiro also argued that Colossal had never tried to hide these facts, but when Live Science contacted Colossal for comment, a spokesperson doubled down on the company's original claim that it has brought back the dire wolf.

In the moa announcement, Shapiro says Colossal will "bring the moa back to life" and Ben Lamm, the company's co-founder and CEO, says scientists will "return it back to the ecosystem."

"Despite Colossal Biosciences' eventual reframing of dire wolf de-extinction as actually creating an ecological replacement using a genetically modified grey wolf, there is no hint in their recent press release that the best we can hope for is an ecological replacement for a New Zealand moa," Seddon told NZSMC.

To recreate the giant moa, scientists will extract DNA from the remaining bones of all nine species and compare it to the DNA of living birds, Shapiro told Time Magazine. Researchers will then be able to pinpoint the specific genetic characteristics of moas and make those changes in the genome of either an emu or a tinamou, the two closest living relatives of moas, she said.

"It makes sense to use tinamous and emus as templates from which to align DNA of moa," Worthy said in his email. "Much work on DNA has shown tinamous are the sister species to moa. Emu are a reasonably close relative as well."

Genetically modified tinamou or emu cells will then be implanted into a surrogate from one of the two birds and left to gestate. Hatchlings will not be released into the wild nor kept in a zoo, according to the announcement, suggesting the birds will live out their lives in a fenced-off nature reserve.

Should the birds escape, Worthy said they wouldn't pose a danger to humans. "Moas wouldn't see humans as a threat, unless perhaps you tried to hug it, and in scaring it likely you would get kicked and quite likely, badly hurt," he said.

Colossal says moa de-extinction will bring benefits for endangered birds along the way; for example, it could inform the development of artificial eggs, which, in turn, may help preserve endangered species.

"There will be undoubted great advances in knowledge along the path towards de-extinction," Worthy said. "We will get [unprecedented] knowledge of the target animals' DNA and for extinct groups such as the moa this will potentially [be] very interesting regarding their evolution, relationships, etc."

But creating an animal that is only like the extinct species in appearance remains "straight out of Frankenstein," Stuart Pimm, a professor of conservation ecology at Duke University in North Carolina, told Time Magazine.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus