IBM and NASA create first-of-its-kind AI that can accurately predict violent solar flares

The new open-source AI model, Surya, is trained on nine years of satellite imagery data and can accurately predict the sun's activity up to two hours into the future. It's 16% more effective than any other tool currently available.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

IBM and NASA scientists have unveiled a groundbreaking artificial intelligence (AI) model that can predict the sun's ferocious outbursts more accurately than ever, giving us a chance to react to dangerous and disruptive solar activity.

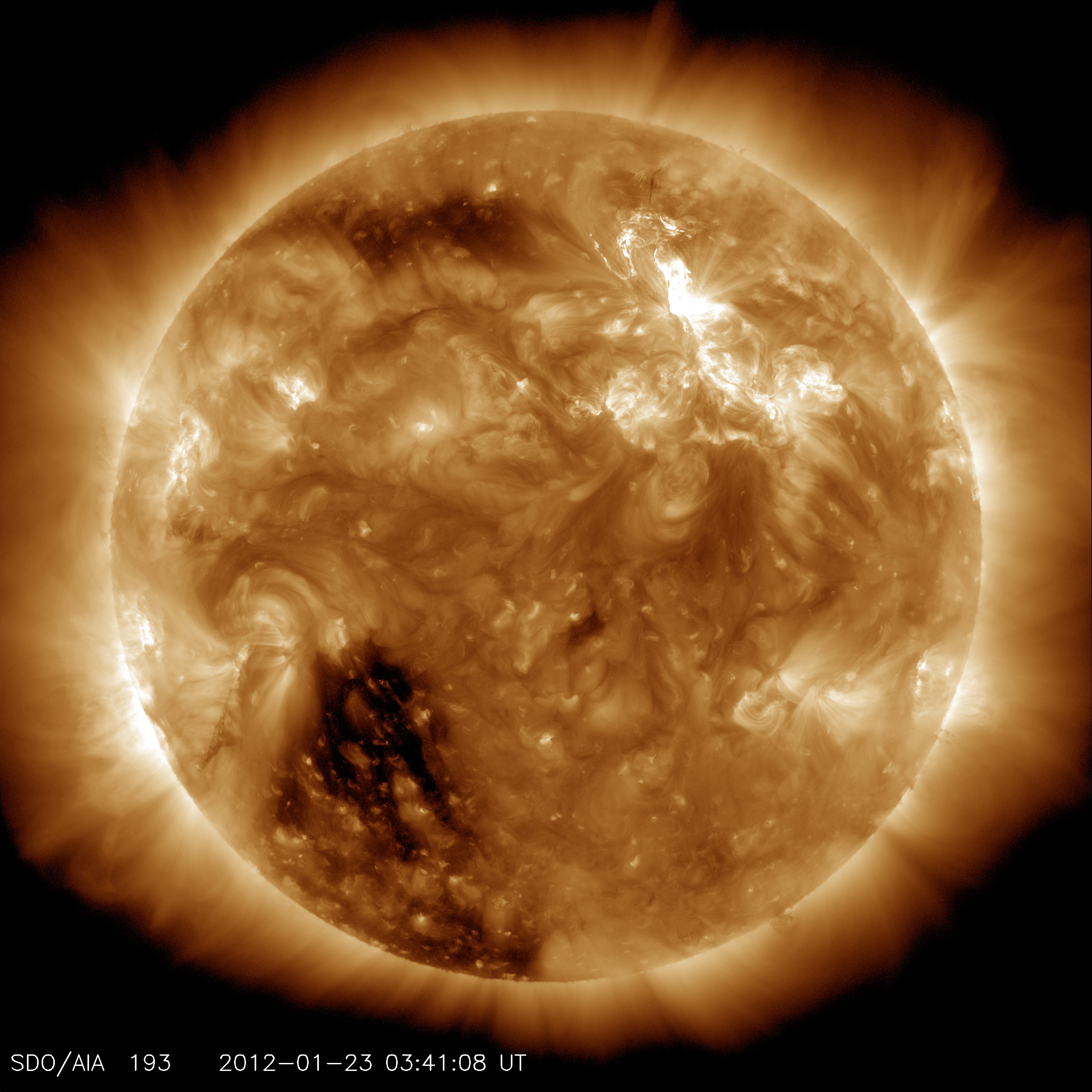

The new AI model, known as "Surya" (Sanskrit for the sun), absorbs the raw images that are captured by the Solar Dynamic Observatory (SDO) satellite — which has been staring directly into the sun for the last 15 years — and processes them quicker than any humans can.

Using this raw data, which IBM representatives said in a statement researchers have barely scratched the surface of, the foundational model can predict violent outbursts before they happen.

That way, we can protect astronauts and equipment in space, and even plan for disruption to power grids and communications systems on Earth.

"We’ve been on this journey of pushing the limits of technology with NASA since 2023, delivering pioneering foundational AI models to gain an unprecedented understanding of our planet Earth," Juan Bernabé-Moreno, the director of IBM Research Europe for the U.K. and Ireland who is in charge of scientific collaboration with NASA, said in the statement.

"With Surya we have created the first foundation model to look the sun in the eye and forecast its moods."

Solar activity has a growing impact on our lives the further we venture into space, and the more we rely on technology on Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Solar flares and coronal mass ejections can knock out satellites, disrupt airline navigation, trigger power blackouts and pose a radiation risk to astronauts, making accurate solar weather prediction increasingly important.

Related: AI is entering an 'unprecedented regime.' Should we stop it — and can we — before it destroys us?

Forecasting storms on Earth is notoriously difficult, the scientists said, and predicting solar storms is even tougher. When solar flares erupt through the sun's magnetic field, it takes eight minutes for that light to reach our eyes — this lag (the eight minutes in which we have no visibility over what has happened) means that scientists need to be even further ahead.

The Surya AI model is comparable to the separate "Prithvi" family of AI models. These models process gigantic volumes of satellite data to create a more accurate representation of Earth in order to better predict its climate and weather, alongside completing other tasks such as mapping deforestation, measuring the impact of flooding and projecting the effect of extreme heat.

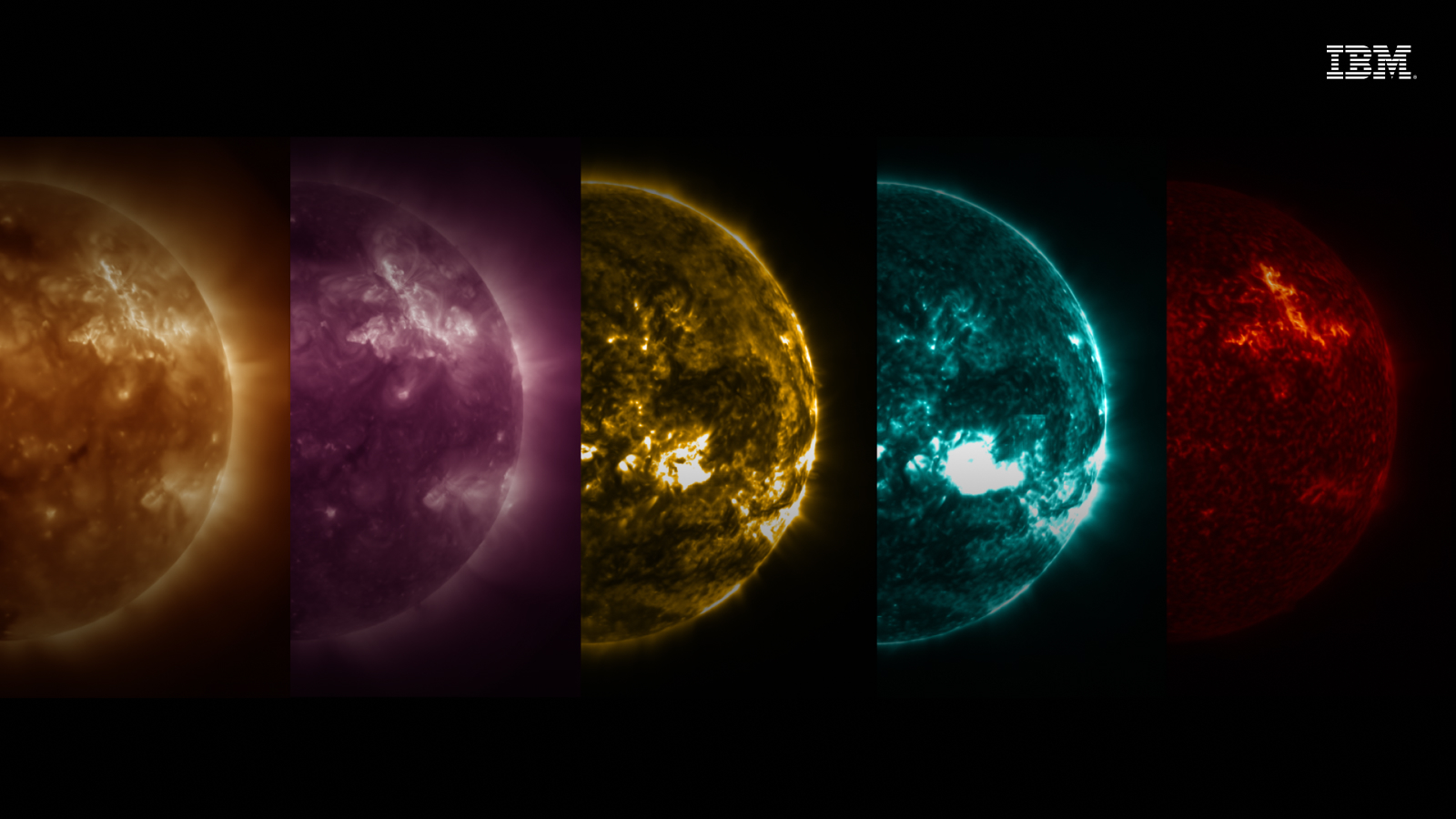

The Surya model is an open-source, 360-million-parameter system designed to learn solar representation through eight Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) channels and five Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) products.

AIA is designed to provide different views at the top of the sun's atmosphere, known as the solar corona — taking images that span 1.3 solar diameters in multiple wavelengths to improve the understanding of the physics behind what we can observe in the sun's atmosphere. HMI, meanwhile, is an instrument that studies oscillations and the magnetic field at the sun's surface.

The system can accurately forecast solar dynamics, solar wind and solar flares, and detect extreme ultraviolet (EUV) spectra.. The scientists say that the novel architecture of Surya means it can learn the underlying physics behind solar evolution. They outlined their findings in a study uploaded Aug. 18 to the arXiv preprint database, meaning that it has not yet been peer-reviewed.

"This is an excellent way to realize the potential of this data," Kathy Reeves, a solar physicist at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who was not involved in the study said in the statement. "Pulling features and events out of petabytes of data is a laborious process and now we can automate it."

Staring directly into the sun

The model’s data comes from the SDO, which orbits the Earth, snapping pictures every 12 seconds. These images capture the sun at different wavelength bands to take the temperature of its layers, which vary from 5,500 degrees Celsius on the surface to up to 2 million degrees Celsius at the corona.

SDO also captures magnetic activity, with emerging sunspots revealed in white light while other imaging tools check the speed of bubbles on the surface and track the twisting of the sun's magnetic lines.

Researchers trained Surya by taking a nine-year excerpt of this data, first harmonizing the different layers — meaning the different types of data are amalgamated to create a more holistic picture — and then experimenting with different AI architectures to process it.

With Surya, they challenged the model to take sequential images and then predict what SDO would see an hour into the future — checking these predictions against the actual observed images.

The sun also has various quirks that the scientists attempted to hardcode into the model — including the fact that the sun rotates faster at its equator than at its poles. Yet, remarkably, they found that Surya was more effective at learning these quirks on its own, from the data, than through any human input.

In testing, the AI model could forecast whether an active region was likely to set off a solar flare an hour before it happened, and in some experiments, they achieved predictions within two hours (when led by visual information). This represents a 16% improvement on existing prediction methods, IBM representatives said in the statement.

The team has made the AI model open-source, and it is now available on GitHub and Hugging Face — an open-source platform that hosts AI models and datasets. SuryaBench, a curated set of datasets and benchmarks aimed at helping researchers better understand the behavior of the sun, is also available to access freely.

Keumars is the technology editor at Live Science. He has written for a variety of publications including ITPro, The Week Digital, ComputerActive, The Independent, The Observer, Metro and TechRadar Pro. He has worked as a technology journalist for more than five years, having previously held the role of features editor with ITPro. He is an NCTJ-qualified journalist and has a degree in biomedical sciences from Queen Mary, University of London. He's also registered as a foundational chartered manager with the Chartered Management Institute (CMI), having qualified as a Level 3 Team leader with distinction in 2023.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus