Mysterious Voynich manuscript may be a cipher, a new study suggests

A newly invented cipher may shed light on how the mysterious Voynich manuscript was made in medieval times.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A unique cipher that uses playing cards and dice to turn languages into glyphs produces text eerily similar to the glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, a new study shows. The finding suggests that an equivalent cipher could have been used to create the mysterious medieval manuscript.

The new cipher — called "Naibbe," from the name of a 14th-century Italian card game — does not decode the medieval Voynich manuscript, but it offers an idea for how the manuscript was made.

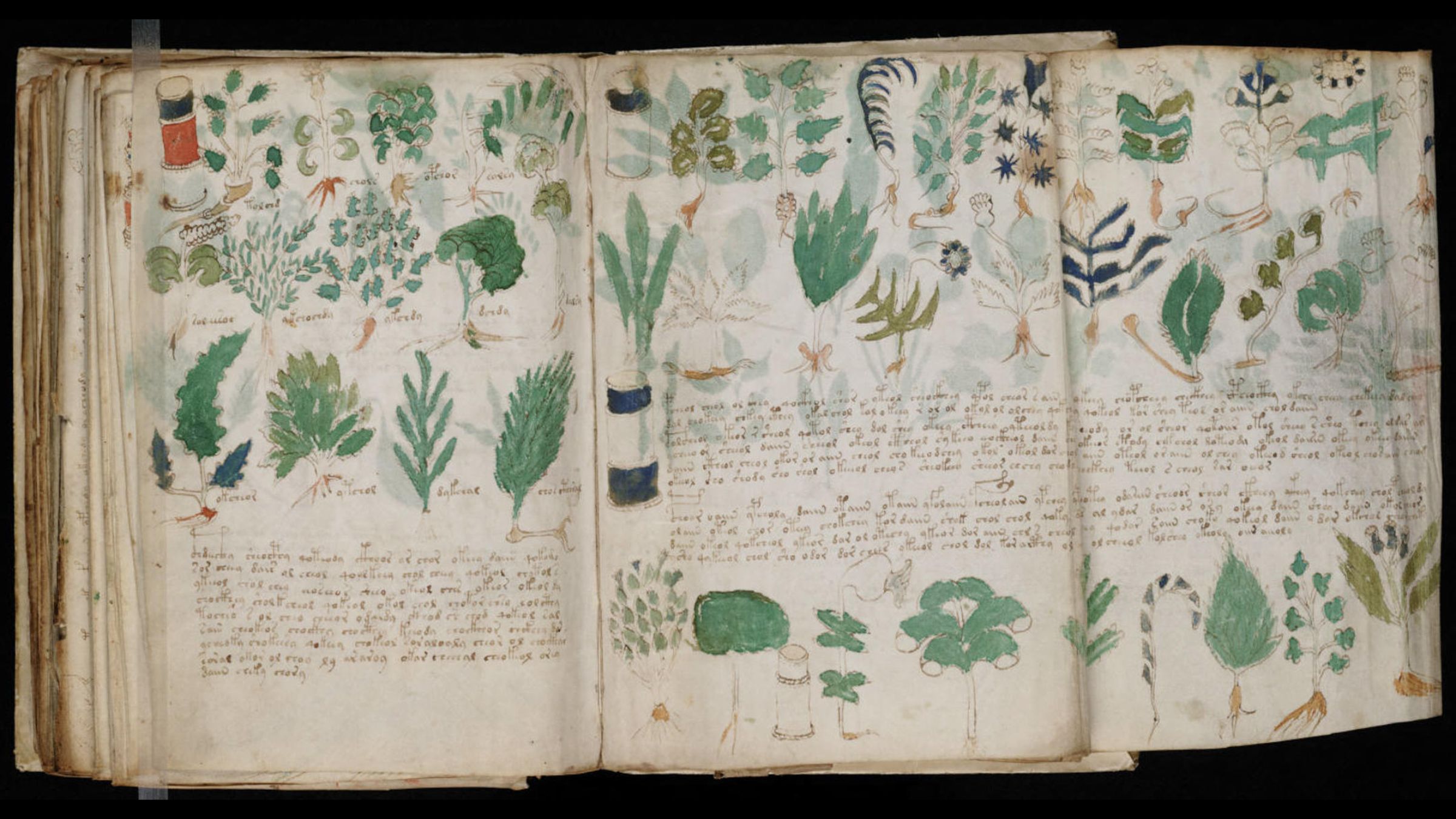

The Voynich manuscript, which has been radiocarbon-dated to the 15th century, contains roughly 38,000 words written in glyphs that have never been translated. Despite more than a century of intense scrutiny, the manuscript has not been explained conclusively. However, it continues to intrigue people, with its bizarre and inexplicable illustrations of plants, astrology and alchemy, including supposedly "biological" depictions of bathing naked women.

Article continues belowIn the new study, published Nov. 26 in the journal Cryptologia, science journalist Michael Greshko investigated one way the manuscript may have come together. He told Live Science that he got the idea for the Naibbe cipher while researching stories about the Voynich manuscript. "It is this fascinatingly mysterious medieval artifact," he said.

Naibbe first uses the number from the throw of a die to break a block of Italian or Latin into single and double letters — so "gatto" (Italian for "cat") could become "g","at" and "to." The cipher then uses the draw of a playing card to determine which of six different tables is used to encrypt the letters into "Voynichese" — the strange and undeciphered glyphs that are apparently grouped into words in the manuscript. The tables are "weighted" by the corresponding number of cards so that the statistical occurrence of the mock-Voynichese glyphs is the same as seen in the manuscript itself.

Greshko's effort is among the leading attempts to explain how the manuscript was made. But it still only approximated Voynichese text, rather than fully replicating it, he said.

Mysterious manuscript

The Voynich manuscript is named after the Polish, British and American book collector Wilfrid Voynich, who acquired it in 1912 from a collection compiled by a Jesuit college near Rome. It is now housed at Yale University.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The manuscript now lies at a nexus of attempts to understand lost languages, yet experts are not entirely sure if Voynichese is even real.

One theory, taken seriously, is that the manuscript is a medieval hoax, illustrated with suitably mysterious and salacious drawings, and that the text of Voynichese glyphs is completely meaningless.

The hoax theory has grown stronger in recent years as more attempts to decipher Voynichese — some of which have used machine learning and other computerized artificial intelligence methods — have failed to crack the code, if there is a code.

But theories that Voynichese is based on a real language and can be deciphered are still prominent, and Greshko's Naibbe cipher is one of the closest attempts yet.

The mock-Voynichese output of the Naibbe cipher has several important similarities to true Voynichese, including the statistical frequencies of glyphs, the length of Voynichese "words," and certain rules of the manuscript's mysterious grammar.

Those commonalities suggested that a similar method was used to create the original Voynich manuscript, Greshko said. "The Naibbe cipher is almost certainly not the way that the manuscript was constructed," he said. "But what it does provide is a fully documented way to reliably go between Latin and something that behaves kind of like the Voynich manuscript."

Cipher technology

Dice and playing cards were chosen as sources of randomness because it was essential for the cipher to be "hand-doable" with the technology of the time, Greshko said. At one point, he thought of taking tokens from a bag — a bit like a bingo caller — but he realized that playing cards were known in Europe at that time.

And while the Naibbe cipher does not faithfully replicate all features of Voynichese — such as the exact incidence of Voynichese words and where they appear in a line or paragraph — the discrepancies could be analyzed for potential relevance, he said.

"My hope is that this becomes adopted as a computational benchmark," Greshko said. "The points of difference between the cipher and the manuscript may point the way to how the text was actually created."

Former satellite engineer René Zandbergen, a renowned expert on the Voynich manuscript who was not directly involved in Greshko's study, said he appreciated Greshko's efforts to create an encoding method to approximate Voynichese.

But Greshko "also makes it clear that he is not suggesting that this is how the manuscript text was generated," Zandbergen said in an email. "He just demonstrates that such a method can be found, and we may assume that there may be others."

Zandbergen added that he is "essentially undecided" about whether the Voynichese text is meaningful or a hoax.

"Some people argue that 'nobody would do that,' but I think that argument is too simplistic," he said. "A more problematic point is that I find it very hard to imagine how it could have been done."

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus