Why did the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima leave shadows of people etched on sidewalks?

The nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of WWII left shadows of people on the ground and buildings. Here's why.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Christopher Nolan's Oscar-winning biopic Oppenheimer has reignited public interest in the historic race to develop atomic weapons.

Yet, while the film dwells on J. Robert Oppenheimer's uneasy conscience and his fear of a future nuclear war, being told from his perspective, it doesn't show the direct consequences of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Yet on the streets of the two stricken cities, the horrifying evidence was plain to see.

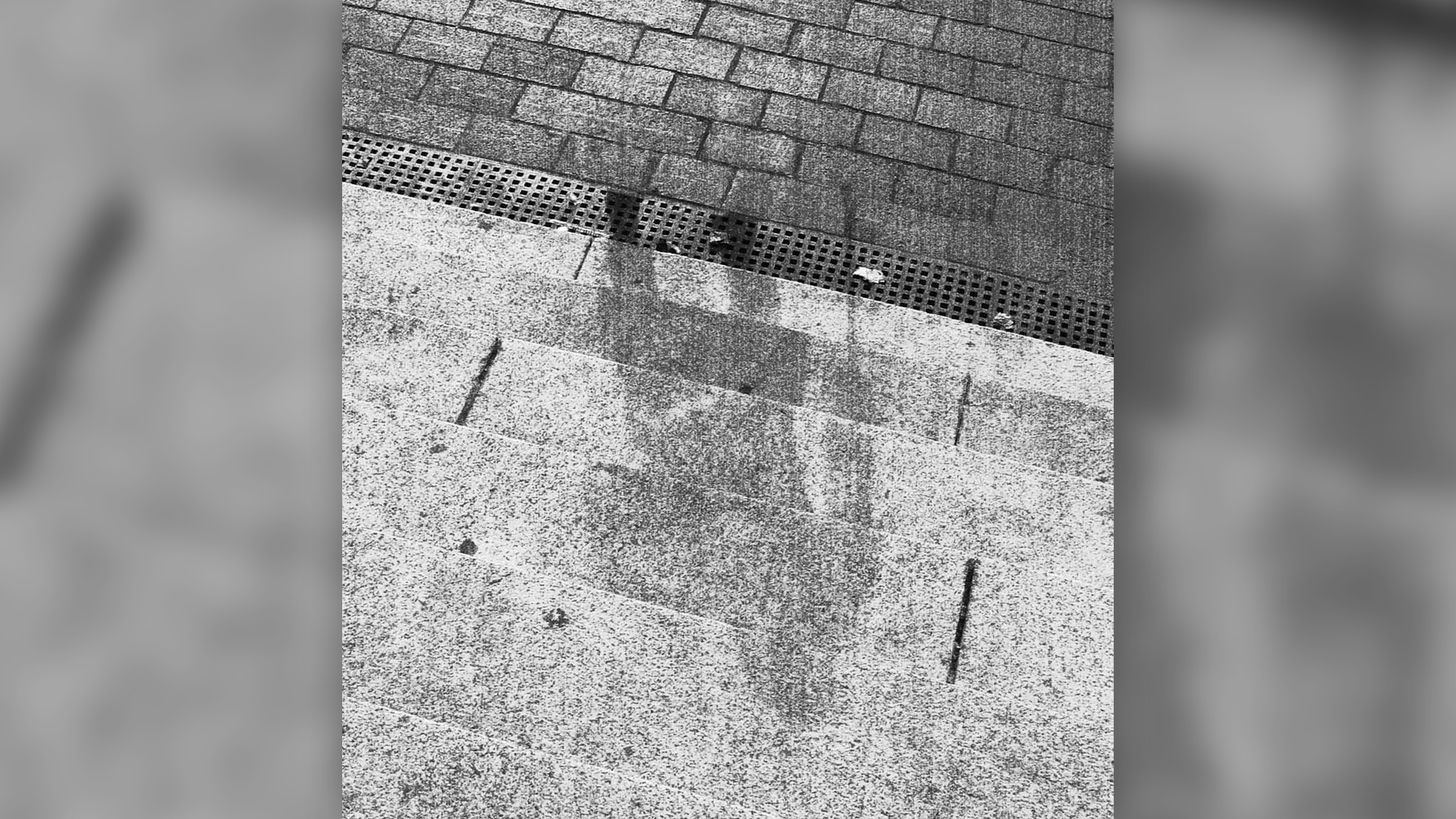

Black shadows of humans and objects, like bicycles, were found scattered across the sidewalks and buildings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two of the largest cities in Japan, in the wake of the atomic blast detonated over each city on Aug. 6 and 9, 1945, respectively.

It's hard to fathom that these shadows likely encapsulated each person's last moments, similar to the ashen casts of ancient volcano victims preserved at Pompeii. But how did these shadows come to be?

According to Dr. Michael Hartshorne, emeritus trustee of the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and professor emeritus of radiology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, when each bomb exploded, the intense light and heat spread out from the point of implosion. Objects and people in its path shielded objects behind them by absorbing the light and energy. The surrounding light bleached the concrete or stone around the "shadow."

In other words, those eerie shadows are actually how the sidewalk or building looked, more or less, before the nuclear blast. It's just that the rest of the surfaces were bleached, making the regularly colored area look like a dark shadow.

Related: Why do nuclear bombs form mushroom clouds?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Powered by fission

The intense energy released during an atomic explosion is the result of nuclear fission. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., fission occurs when a neutron strikes the nucleus of a heavy atom, like the isotopes uranium 235 or plutonium 239. (An isotope is an element with varying numbers of neutrons in its nucleus.) During the collision, the element's nucleus is broken apart, releasing a large amount of energy. The initial collision sets off a chain reaction that continues until all of the parent material is exhausted.

"The chain reaction occurs in a pattern of exponential growth that last[s] a millisecond or so," said Alex Wellerstein, an assistant professor of science and technology studies at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. "This reaction splits about a trillion, trillion atoms in that period of time before the reaction stop[s]."

The atomic weapons used in the 1945 attacks were fueled by uranium 235 and plutonium 239 and released a massive amount of heat and very shortwave, gamma radiation.

Energy flows as photon waves of varying lengths, including in long waves, like radio waves, and in shortwaves, like X-rays and gamma-rays. Between long waves and shortwaves lie visible wavelengths that contain energy that our eyes perceive as colors. However, unlike energy with longer waves, gamma radiation is destructive to the human body because it can pass through clothing and skin, causing ionizations, or the loss of electrons, that damage tissue and DNA, according to Columbia University.

The gamma radiation released by the atomic bombs also traveled as thermal energy that could reach 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,538 degrees Celsius), Real Clear Science reported. When the energy hit an object, like a bicycle or a person, the energy was absorbed, shielding objects in the path and creating a bleaching effect outside the shadow.

In fact, there were likely many shadows initially, but "most of the shadows would have been destroyed by subsequent blast waves and heat," Hartshorne told Live Science.

Fat Man and Little Boy

On Aug. 6, 1945, an atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy detonated 1,900 feet (580 meters) above Hiroshima, Japan's seventh-largest city. According to the World Nuclear Association, the explosion was equivalent to 16,000 tons (14,500 metric tons) of TNT exploding, which sent a pulse of thermal energy rippling across the city. The pulse flattened 5 square miles (13 square kilometers) of the city. Almost one-quarter of the population of Hiroshima died immediately. Another quarter died of the effects of radiation poisoning and cancer in the months that followed.

Three days after that blast, the United States detonated a second atomic bomb, nicknamed Fat Man, over the city of Nagasaki, some 185 miles (300 km) northeast of Hiroshima. The plutonium 239 bomb released a 21,000-ton (19,000 metric tons) explosion that produced similar patterns of destruction and death across the city.

Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's surrender on Aug. 15 and signed the formal declaration on Sept. 2, 1945, ending the hostilities in the Pacific War and bringing World War II to a close.

Related: Hiroshima fallout may offer a glimpse of the early solar system

Remembrance

The United States targeted both Japanese cities during the war for their military significance, as well as their relative safety from prior bombing raids; because the cities were largely untouched by raids, the damage inflicted by the atomic bombs would be easily measured, according to Atomic Archive, an online repository of documents related to the development and use of atomic weapons.

As time has passed, the long-term consequences of the radiation released by each bomb has raised significant questions about their use. Many of the shadows etched into the stone were lost to weathering and erosion by wind and water. Several nuclear shadows have been removed and preserved in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum for future generations to ponder these events.

"I think it is very important to keep in mind the consequences of the use of nuclear weapons," Wellerstein told Live Science. "It is very easy to regard these weapons as tools of statecraft and not weapons of mass destruction. The nuclear shadows serve as a potent reminder of the human cost of [atomic weapon] use."

Editor's note: This article was last updated on March 27 to incorporate information about the Oppenehimer film as well as the development of the atomic bomb.

As a scientist, Stacy Kish has focused her research on Earth science, specifically oceanography and climate change. As a science writer, she explores all aspects of science from mites living books to noctilucent clouds, stretching across the mesopause. She finds every aspect of science intriguing and considers a good day to be one where she learns something new and unexpected. In her free time, she works on perfecting new cake recipes to share with others.

- Ben TurnerActing Trending News Editor

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus