Decades-long droughts doomed one of the world's oldest civilizations

A series of lengthy droughts brought about the fall of the Indus Valley Civilization, a new study finds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A series of severe, decades-long droughts ushered the end of the Indus Valley Civilization, one of the world's oldest civilizations, a new study finds.

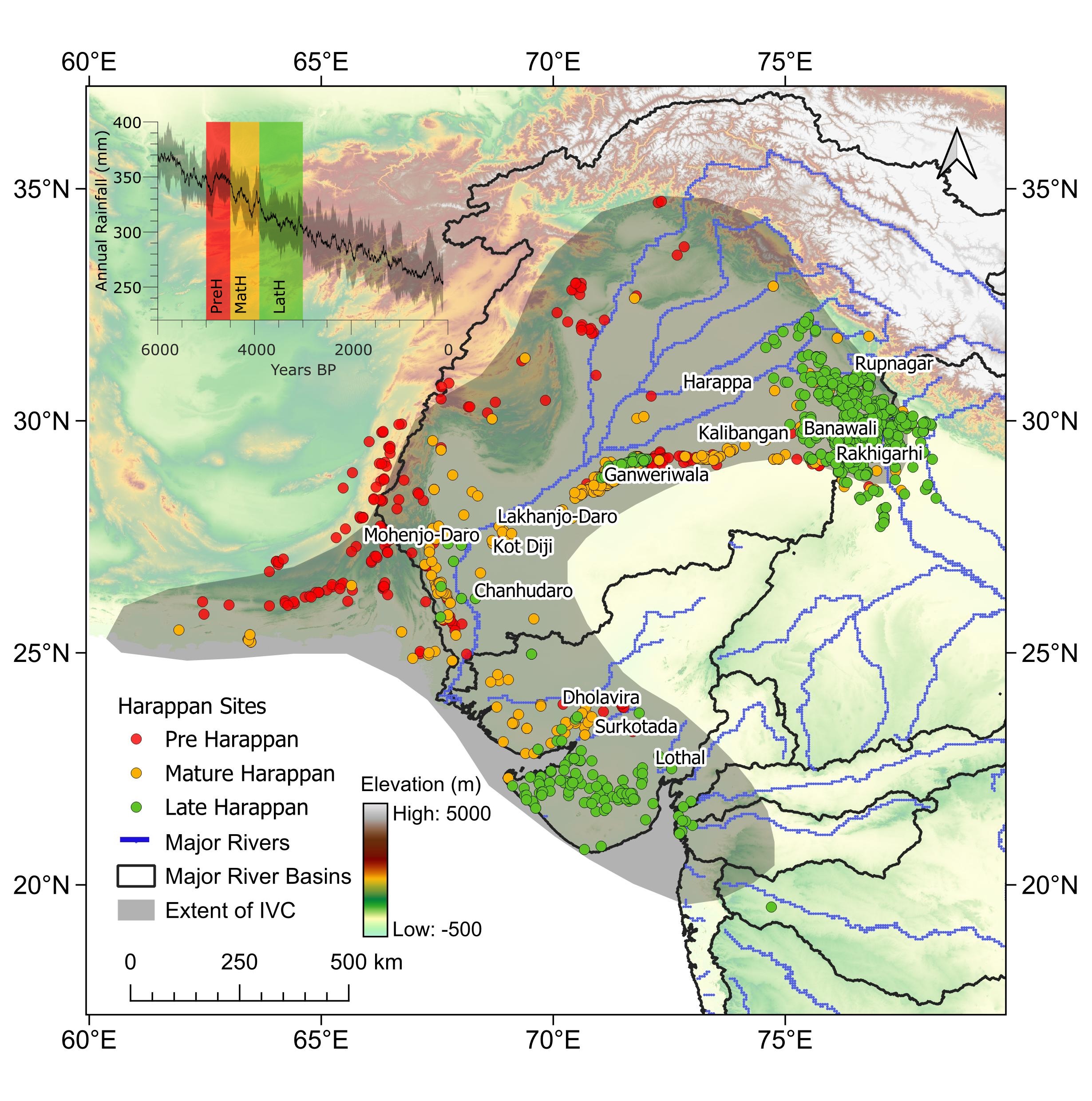

This Indus Valley Civilization (also known as the "Harappan" civilization) flourished between 5,000 and 3,500 years ago in a region that stretched across the modern-day India-Pakistan border. Its people created cities, such as Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, which had sophisticated water-management systems. They also created a written script, which remains undeciphered by modern scholars, and they traveled to Mesopotamia, where they conducted trade.

Why their civilization declined has long been a matter of debate. Now, in a new study, published Thursday (Nov. 27) in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, scientists say that lengthy droughts played a sizable role.

"Successive major droughts, each lasting longer than 85 years, were likely a key factor in the eventual fall of the Indus Valley Civilization," the scientific team wrote in a statement. As these droughts got worse, populations within the society shifted to areas where substantial water sources still existed, the researchers found.

Eventually, cities across the region collapsed. A century-long drought that started about 3,500 years ago "coincides with widespread deurbanization and cultural abandonment of major [cities]," the team wrote in the paper.

Climate simulations

For the analysis, the team used three different publicly available global climate simulations — complex computer simulations that use a vast amount of data to determine how the climate has changed over thousands of years. They used these to determine how rainfall and temperature changed between 5,000 years ago to 3,000 years ago in the area where the Indus Valley Civilization once thrived. All three simulations showed the existence of the droughts.

"The consistent decline in rainfall from 5000 to 3000 years [ago] across all simulations ensures that features such as multi-century droughts, monsoon weakening, or winter rainfall shifts are real, persistent signals and not artifacts of a single model," study lead author Hiren Solanki, a doctoral student at the Indian Institute of Technology at Gandhinagar, told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team put the rainfall and temperature data into a hydrological model to determine how rivers, streams and other bodies of water in the region changed over time. They compared this to archaeological data showing where settlements existed and saw that they tended to shift over time to stay close to water.

To double check their results, the team looked at previous studies that analyzed how quickly stalagmites and stalactites in caves in the region grew. These structures grow slower at times when there is less precipitation, providing indirect evidence of drought. As an additional method to determine how precipitation patterns changed, the team also looked at previous studies that show how sedimentary deposits in lakes changed in the region over time.

By comparing the simulation data with the cave and lake-deposit data, they could confirm that the data from the simulations was fairly accurate.

Nick Scroxton, a research scientist of hydrology, paleoclimate and paleoenvironments at University College Dublin who was not involved with the research, praised the study.

"The Indus River is clearly important to the Harappan and modelling the river flows helps us understand how changing rainfall patterns might have influenced changes in both urban settlement and agricultural practices," Scroxton told Live Science in an email.

Liviu Giosan, a geoscientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts who was not involved with the study, also spoke positively of the paper, praising the "sophisticated modeling" that the team did. The "results are a significant step ahead in studying the role played by the hydroclimate in the evolution of ancient civilizations" Giosan told Live Science in an email.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus