Last common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals possibly found in Casablanca, Morocco

A collection of bones from Casablanca holds important new clues to the origins of modern humans and Neanderthals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The discovery of 773,000-year-old fossils in a cave in Morocco is transforming the geography of human origins by placing the start of the modern-human lineage squarely in northwestern Africa, according to a new study.

In the research, published Wednesday (Jan. 7) in the journal Nature, a team of Moroccan and French researchers detailed their analysis of a handful of bones they think represent the last common ancestor of modern humans (Homo sapiens), Neanderthals and Denisovans.

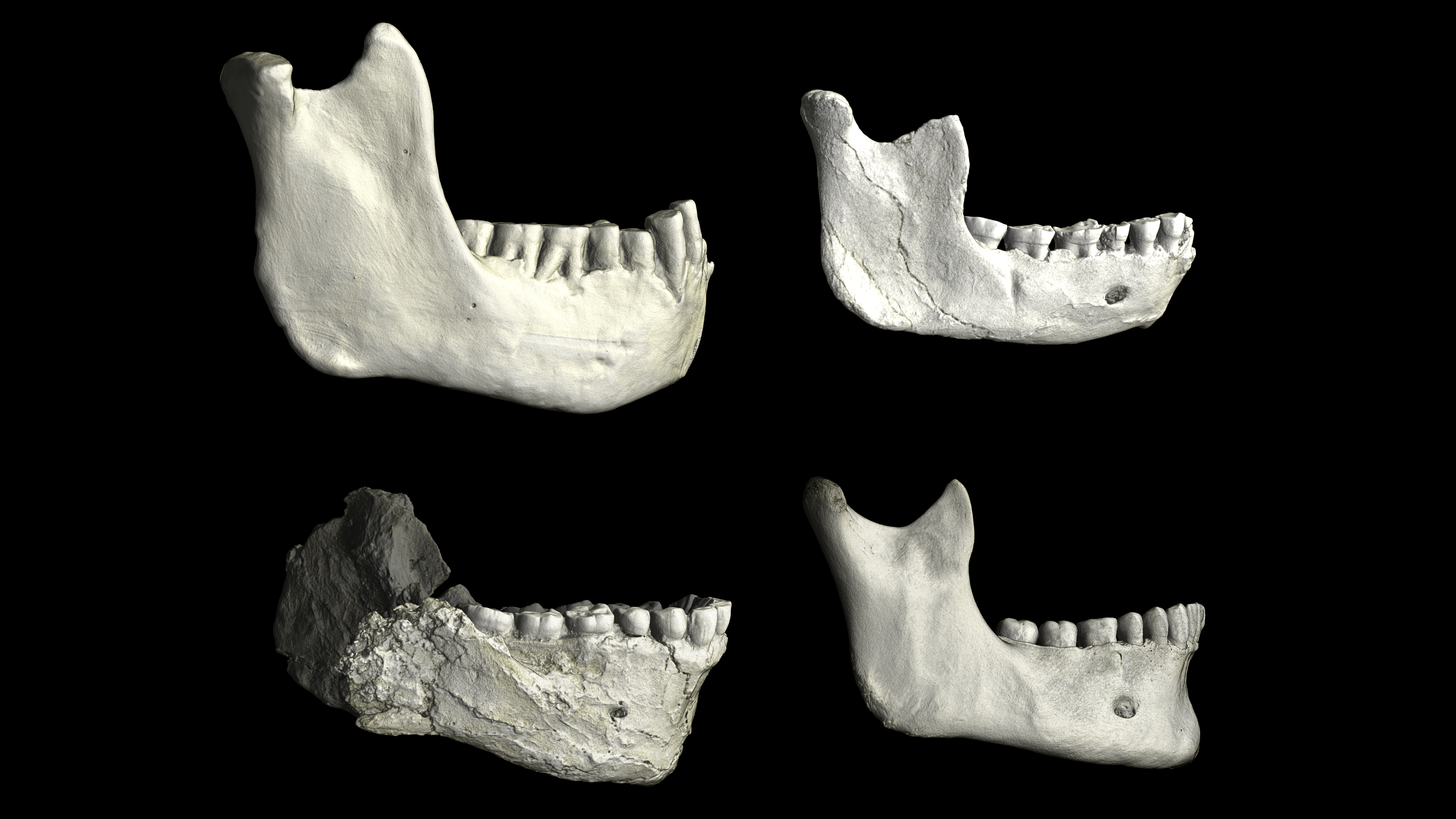

The researchers discovered the fossils in a cave called Grotte à Hominidés (Cave of Hominids) at the site of Thomas Quarry I in Casablanca, Morocco. The bones consist of three partial lower jaws, several vertebrae and numerous individual teeth, all of which share some characteristics of Homo erectus but also have traits distinct from this human ancestor.

Article continues belowAdditionally, there were numerous stone tools at the site, and one leg bone suggests that hyenas might have dined on the hominins. By testing the magnetic properties of 180 samples of sediment from around the fossils, the researchers found that the sequence spanned the Matuyama-Brunhes magnetic-field reversal, a geological event that occurred 773,000 years ago.

The new discovery fills a major gap in the African hominin fossil record between 1 million and 600,000 years ago, study co-author Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, told Live Science in an email. Genetic evidence has suggested that, during this time span, the last common ancestor of modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans was living in Africa.

Hublin and colleagues think the Thomas Quarry fossils are the best candidates yet for the "root" of the ancestral tree that led to our species and our archaic cousins.

While the early chapters of the story of human evolution took place in eastern and southern Africa, the last million years of our evolution are complicated by our ancestors' tendency to wander throughout Africa and Eurasia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After H. erectus evolved in Africa around 2 million years ago, some groups spread eastward, reaching as far as Oceania. But others stayed put, evolved further and spread north into Europe around 800,000 years ago, where the groups from Spain are known as Homo antecessor and are the most likely direct ancestor of Neanderthals.

The newly analyzed Moroccan fossils are from roughly the same time period as H. antecessor and share some of their distinctive traits, which "may reflect intermittent connections across the Strait of Gibraltar that deserve further investigation," Hublin said. The Thomas Quarry fossils, however, are distinct from both H. erectus and H. antecessor.

"This supports a deep African origin for Homo sapiens and argues against Eurasian origin scenarios," Hublin said.

More work on the exceptionally rich fossil record of North Africa is needed to expand an understanding of human origins that is based largely on eastern and southern Africa, Hublin said, particularly since the clearest early evidence of H. sapiens comes from the 300,000-year-old site of Jebel Irhoud in Morocco.

A focus on this geographic area may also reveal new clues about the split between our species and our Neanderthal and Denisovan cousins.

"While we cannot claim that the emergence of the lineage leading to Homo sapiens occurred exclusively in North Africa," Hublin said, "the [new] Moroccan fossils strongly suggest that populations close to the divergence between the Homo sapiens lineage and those leading to Neanderthals and Denisovans were present there at that time."

John Hawks, a biological anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the study, agreed with the researchers' conclusions.

"It's clear from the new study that these fossils don't fit easily into the variation of Homo erectus in some ways," Hawks told Live Science. "It's likely that they're close to the common ancestor that gave rise to Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern people."

But it's unclear what the Thomas Quarry fossils should be called. "In my way of thinking, they might be the earliest fossils that we should really call Homo sapiens," Hawks said.

Hublin is hesitant to classify the fossils as a particular species or population, particularly because there are only a handful of fragmentary remains from Thomas Quarry. "Palaeoproteomic analyses are planned and could potentially help to elucidate the relationships between the European and North African fossils," Hublin said.

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus