Remote region in Greece has one of the most genetically distinct populations in Europe

A genetic analysis of the Deep Maniots living in Greece's southern Peloponnese region has revealed a close-knit, patriarchal community with roots in the Bronze Age.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A group of people living in the far southern reaches of Greece's Peloponnesian Peninsula have been genetically isolated for over a millennium and can trace their roots back to the Bronze Age, an analysis of their DNA reveals.

A new genetic study shows that this group, known as the Deep Maniot Greeks, are paternally descended from ancient Greeks and Byzantine-era Romans. Long-term genetic isolation and strict patriarchal clans likely contributed to the unique genetics of the Deep Maniot Greeks over the past 1,400 years, according to the study authors.

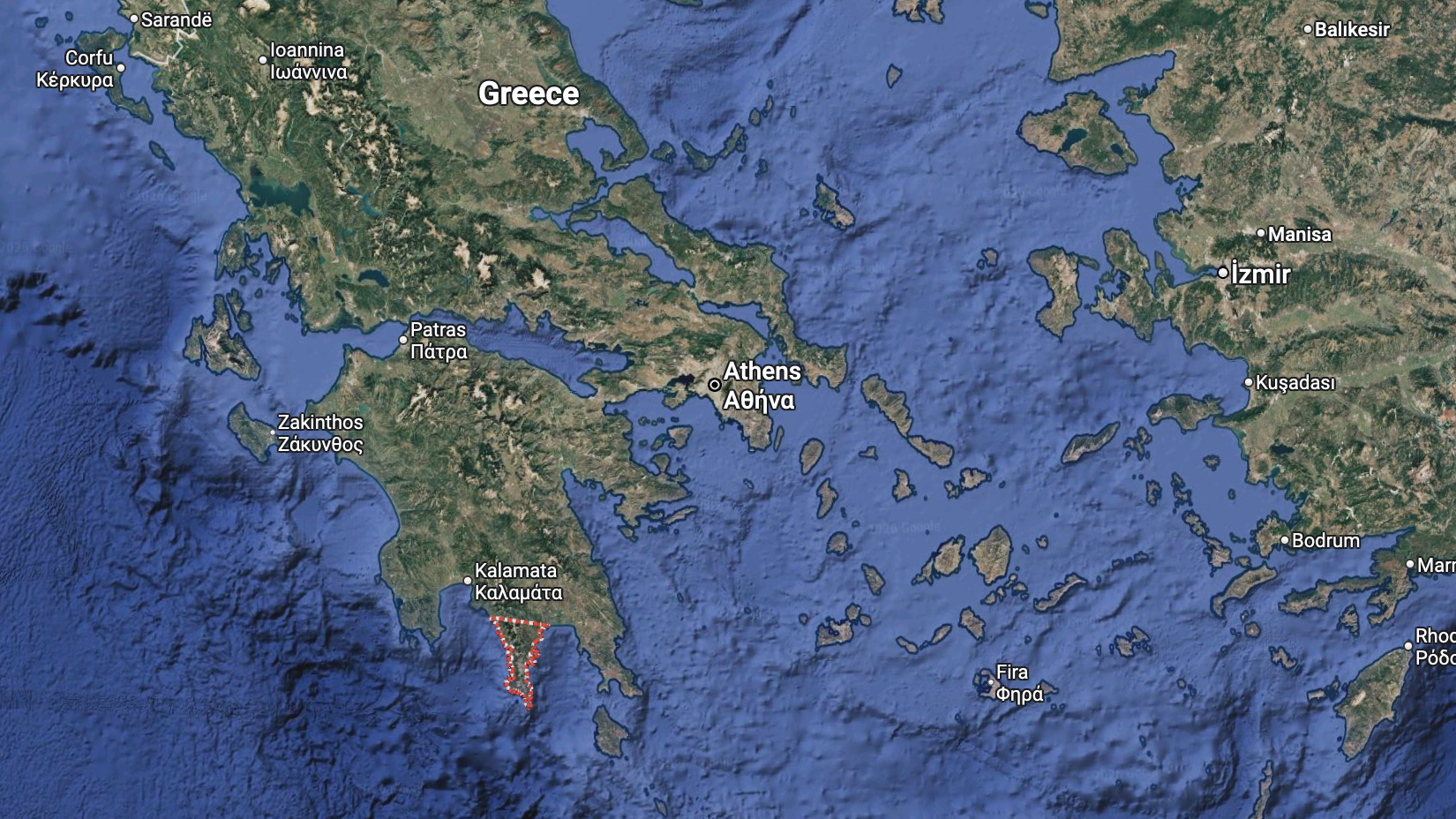

The Mani Peninsula is the middle of three peninsulas that extend south from mainland Greece. In ancient times, the area was part of the Laconia region, which was dominated by the city-state Sparta in the seventh century B.C. Much of the Greek Peloponnese region experienced demographic upheaval as Slavic peoples invaded in the sixth century A.D. However, the Mani Peninsula was spared, and the Deep Maniots who lived in the far southern part of the peninsula became geographically and culturally isolated from the rest of Greece.

Article continues belowIn a study published Wednesday (Feb. 4) in the journal Communications Biology, researchers analyzed the DNA of more than 100 living Deep Maniots and discovered that they represent a "genetic island" due to long-standing isolation.

"Our results show that historical isolation left a clear genetic signature," study lead author Leonidas-Romanos Davranoglou, a zoologist at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, said in a statement. "Deep Maniots preserve a snapshot of the genetic landscape of southern Greece before the demographic upheavals of the early Middle Ages."

During Europe's Migration Period (circa A.D. 300 to 700), which is sometimes called the "Barbarian Invasions," various groups of people — including Germanic tribes, the Visigoths, the Huns and early Slavs — moved throughout the continent. This resulted in numerous waves of migration, only some of which were historically documented. Ancient DNA research has begun to tease out these Migration Period population waves.

But these Migration Period movements did not seem to affect the Deep Maniots, according to historical, linguistic and archaeological evidence. So Davranoglou and colleagues turned to DNA analysis of modern Maniots to investigate why.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers looked at genetic markers on the Y chromosomes (which are passed down from father to son) of 102 people with Deep Maniot ancestry on their paternal side, as well as mitochondrial DNA (passed down from mother to child) sequence data from 50 people with maternal Deep Maniot ancestry.

The DNA analysis revealed that Deep Maniots have an extremely high frequency of a rare paternal lineage that originated in the Caucasus region around 28,000 years ago, the researchers wrote in the study. And when compared with the DNA of present-day mainland Greeks, the DNA of Deep Maniots lacked evidence of common lineages that came from Germanic and Slavic peoples during the Migration Period.

Taken together, these results suggest that genetic drift (a reduction in genetic variation due to a small population size) played an important role in shaping the paternal lineage of Deep Maniots, the researchers wrote, forming a kind of "genetic island." This island of paternal ancestry is rooted in the ancient Balkans and West Asia and is strongly linked to Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman-period Greek-speaking populations, they noted.

Analysis of the maternal Deep Maniot lineages through mitochondrial DNA revealed a more complex genetic picture, however. The researchers identified 30 distinct maternal lineages in their population sample of 50 Deep Maniots. Most of those lineages have connections to Bronze Age and Iron Age people from Western Eurasia, but several appear to be Deep Maniot-specific, showing no close matches to other present-day European populations.

"These patterns are consistent with a strongly patriarchal society, in which male lineages remained locally rooted, while a small number of women from outside communities were integrated," study co-author Alexandros Heraclides, an epidemiologist at European University Cyprus, said in the statement.

Both the paternal and maternal DNA markers also show evidence of a founder effect, which happens when a new population is established by a very small subset of a larger population. The new population includes only the genes of its small number of founders and, over time, becomes distinct from the larger population.

The genes of present-day Deep Maniots reveal that there was a founder effect among their paternal ancestors around A.D. 380 to 670. As a result, over 50% of Maniot men today descend from a single male ancestor from the seventh century. There was also a founder effect among their maternal ancestors around 540 to 866, the team found, suggesting the number of both maternal and paternal lineages shrank around the same time.

The DNA study suggests that the Deep Maniot population "represents a snapshot of the genetic landscape of the Greek-speaking world prior to the demographic turmoil of the Migration Period," the researchers wrote.

"Many oral traditions of shared descent, some dating back hundreds of years, are now verified through genetics," study co-author and independent researcher Athanasios Kofinakos said in the statement.

Davranoglou, L., Kofinakos, A. P., Mariolis, A. D., Runfeldt, G., Maier, P. A., Sager, M., Soulioti, P., Mariolis-Sapsakos, T., & Heraclides, A. (2026). Uniparental analysis of Deep Maniot Greeks reveals genetic continuity from the pre-Medieval era. Communications Biology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-026-09597-9

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus