10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2025

Findings about our human ancestors continue to surprise us, especially those from 2025.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Our understanding of how our species evolved has improved dramatically since we first began analyzing ancient DNA. This year, researchers made impressive discoveries across 3 million years of human evolution, most of which relied on DNA, genomic or proteomic analyses.

Here are 10 major findings about human ancestors and our close ancient relatives that scientists announced in 2025.

1. Two new species of human relatives were discovered in Ethiopia.

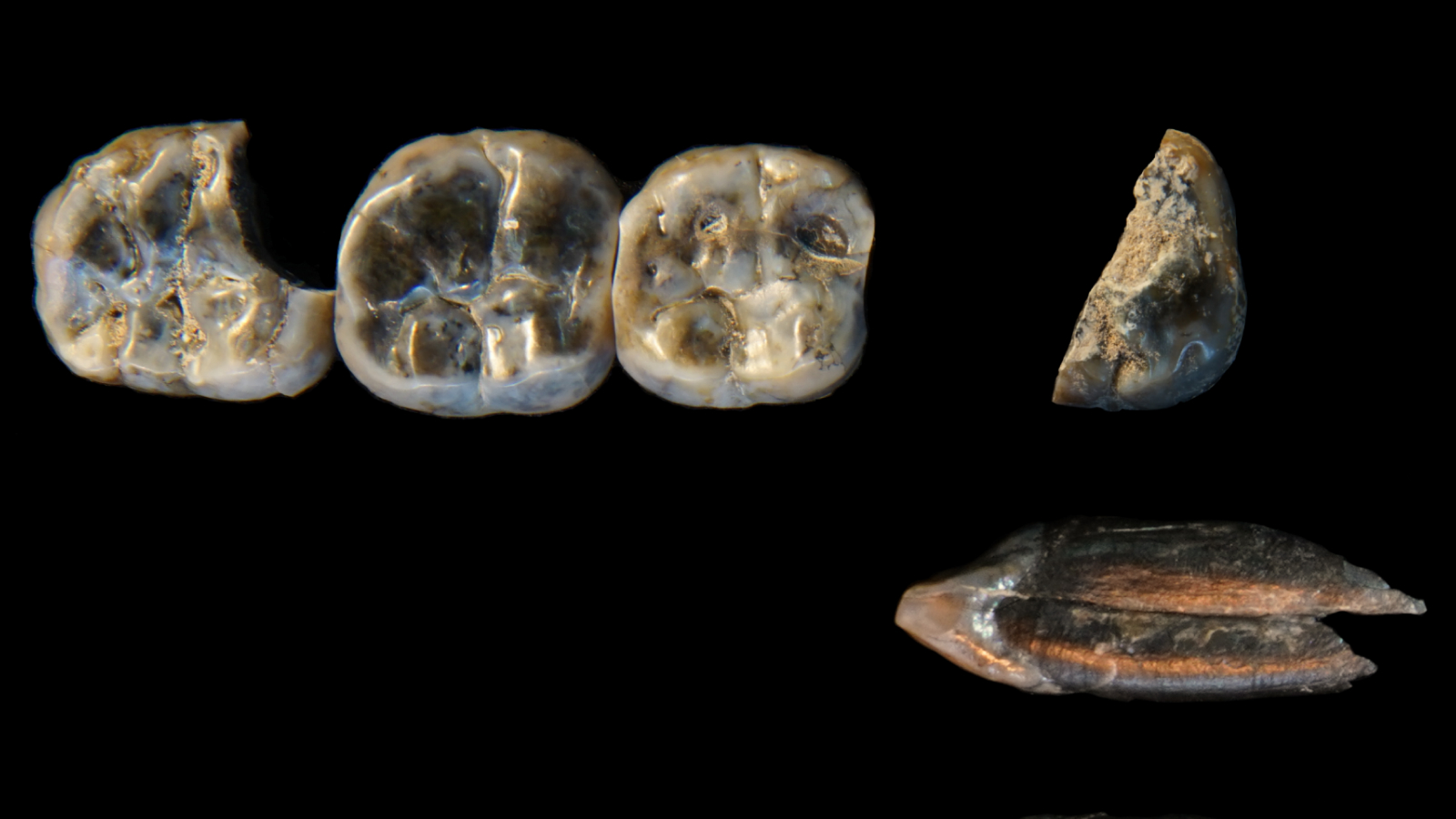

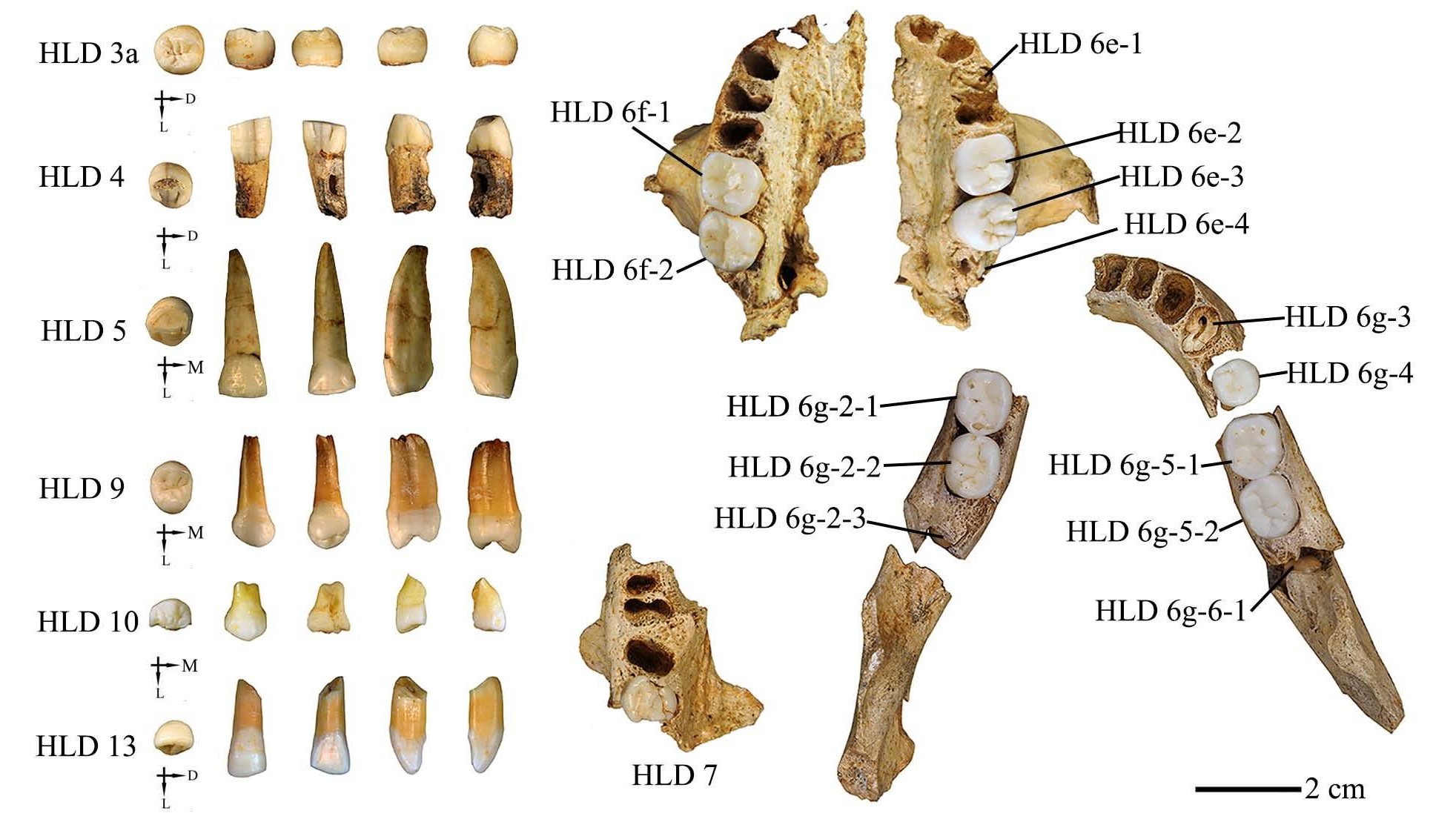

A handful of teeth found at the Ledi-Geraru site in Ethiopia suggest that diverse species of human relatives unlike any seen before were roaming the area 2.6 million years ago.

Article continues belowIn August, researchers announced the discovery of 13 teeth. Ten are estimated to be 2.63 million years old and don't belong to either Australopithecus afarensis or Australopithecus garhi, the two australopithecine species known from the area. Because the teeth don't have any especially unique features and aren't in a skull, the newfound species they may come from does not have an official name. Researchers are calling it the Ledi-Geraru Australopithecus.

In the same study, the researchers found two teeth that are 2.59 million years old and one that is 2.78 million years old. All of them seem to belong to the genus Homo, which would make them some of the earliest remains of our own genus.

The dental discoveries mean that at least three archaic human relatives were living in this region of Ethiopia around 2.5 million years ago.

2. Imported stone tools show our relatives were much smarter than we thought.

Hundreds of stone tools discovered in Kenya revealed that our ancient relatives had a high degree of forward planning 600,000 years earlier than experts previously thought.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In an August study, researchers looked at more than 400 stone tools from the site of Nyayanga dated to 3 million to 2.6 million years ago. The tools were likely not made by our genus. While the tools were fairly basic — flakes chipped off of a larger stone — the stones used to make them came from locations more than 6 miles (9.7 kilometers) away.

The fact that hominins were transporting stones from far away to make tools suggests an excellent ability to plan ahead, long before our genus Homo arose.

3. Earliest evidence of Homo erectus found in Georgia

In July, researchers announced the discovery of a 1.8 million-year-old jawbone from Homo erectus at the site of Orozmani in the Republic of Georgia. In 2022, the paleoanthropologists had found a single tooth that they thought was from H. erectus, and the jawbone discovered this year clinched the identification.

H. erectus was our direct ancestor and evolved around 2 million years ago in Africa. It was also the first human ancestor to leave Africa, and eventually ended up in parts of Europe, Asia and Oceania.

To date, the earliest evidence of H. erectus outside Africa comes from Orozmani and a second site in Georgia called Dmanisi, suggesting human ancestors settled in the Caucasus region shortly after leaving Africa.

4. A mystery human reached Indonesia 1.5 million years ago.

Stone tools discovered on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi this year suggest that either H. erectus or an unknown human relative reached Oceania nearly 1.5 million years ago. This matches up well with previous evidence that H. erectus arrived on the island of Java around 1.6 million years ago.

But because no ancient skeletal remains have been found on Sulawesi yet, researchers are unsure if the toolmaker was indeed H. erectus. Another candidate could be H. floresiensis, the diminutive "hobbit" species, which has been found on the neighboring island of Flores. Some researchers think the hobbits originally came from Sulawesi.

Additional excavation on Sulawesi may eventually clarify which species called the island home.

5. Humans arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago.

Genetic research published in November showed that Homo sapiens reached Australia 60,000 years ago, likely via two different routes through the Western Pacific. This finding appears to settle a long-standing debate about humans' arrival on the continent — a feat that required expert knowledge of watercraft and sailing.

The new DNA evidence supports archaeological evidence, including stone tools and pigments on cave walls, of a "long chronology" in which the first arrivals showed up around 60,000 to 65,000 years ago.

But not everyone is convinced. In a July study, researchers used the fact that some Indigenous Australians have Neanderthal DNA to suggest that Australia wasn't populated until about 50,000 years ago — an idea known as the "short chronology."

More research into the origins of the earliest Australians is forthcoming.

6. Drought may have doomed the "hobbits."

By 50,000 years ago, H. floresiensis seems to have disappeared from Flores. In December, researchers published a study suggesting that drought may have fueled their demise.

While studying the rainfall on Flores, scientists discovered that it declined considerably between about 76,000 and 61,000 years ago and that the population of an elephant relative called Stegodon, which the hobbits hunted, disappeared around 50,000 years ago.

The researchers think decreased rainfall led to the reduction in the Stegodon population, which made life more difficult for the hobbits. And if modern humans also reached Flores — perhaps part of the wave of people who eventually settled Australia — the pressure of competition from another species may have wiped out H. floresiensis.

7. Denisovans got a face.

Our extinct relatives the Denisovans were first discovered in 2010 based on DNA extracted from a tiny finger bone. But until this year, no one knew what a Denisovan skull looked like.

Researchers debated for years what species the thick jawbone, recovered off the coast of Taiwan in 2000, came from, with some suggesting H. erectus and others suggesting H. sapiens. But using paleoproteomic analysis, researchers announced in May that the jawbone was from a male Denisovan.

Ancient proteins also revealed in June that a skull discovered in China in 1933, called the "Dragon Man," is from a Denisovan, finally putting a face to the name. But while Dragon Man has now been slotted into the story of human evolution, it is not yet clear whether the group should be considered a separate species, Homo longi.

And in September, researchers reconstructed a 1 million-year-old squashed skull from China and suggested that it may have been a Denisovan ancestor rather than H. erectus.

These three discoveries are pointing paleoanthropologists to clues about the origins and spread of the mysterious Denisovans — a task that will surely continue in the coming years.

8. Denisovan DNA helped Native Americans survive.

Researchers announced in August that some people with Indigenous American ancestry carry Denisovan genes, likely passed on through Neanderthals who mated with modern humans.

In looking at a protein-coding gene called MUC19, scientists discovered that 1 in 3 Mexicans alive today has a version of the gene similar to Denisovans' and that it likely "hitched a ride" from Neanderthals. Essentially, Neanderthals got the gene from mating with Denisovans and then passed it along when they mated with humans. This is the first time scientists have found a Denisovan gene in humans that came via Neanderthals.

Exactly what the Denisovan variant of the MUC19 gene does is currently unclear, but the researchers think it must have been beneficial to the earliest Americans for it to be preserved in the human genome.

9. Interbreeding was rampant among our archaic relatives.

The story of human evolution has gotten wonderfully messy since the genomic revolution. DNA and protein analyses have revealed new groups like the Denisovans, as well as the mating of Neanderthals, modern humans and Denisovans. But this year brought a few surprise pairings as well.

In August, researchers announced that a handful of 300,000-year-old teeth suggested humans and H. erectus may have interbred in China. The teeth had an unusual combination of ancient features, like thick molar roots, and modern features, like small wisdom teeth, that could mean two different species were sharing their genes.

Researchers announced in March that Neanderthals, modern humans and a mysterious third lineage lived alongside one another in caves in what is now Israel around 130,000 years ago. The Homo groups may have mixed and mingled for 50,000 years, potentially sharing cultural practices in addition to genetic material.

And in November, a DNA study of humans' arrival in Australia suggested that, along the way, these early human pioneers likely interbred with one or more archaic human groups, such as H. longi, Homo luzonensis or H. floresiensis.

Although we can see genetic differences among these groups using 21st-century technology, perhaps our earliest ancestors simply saw Neanderthals, Denisovans and others as fellow humans.

10. Most Europeans had a dark complexion until 3,000 years ago.

In a study published in July, scientists found that the genes for lighter skin, lighter hair and lighter eyes emerged among Europeans only about 14,000 years ago and that, until 3,000 years ago, most Europeans had dark skin, hair and eyes.

The researchers determined this from 348 samples of ancient DNA from archaeological sites spread throughout Western Europe and Asia. The first humans to reach Europe around 50,000 years ago carried genes for dark complexions. Once lighter traits emerged, they appeared only sporadically in the genetic data until fairly recently. By about 1000 B.C., those lighter traits became widespread in Europe.

Whether lighter skin, hair and eyes had any sort of evolutionary advantage for early Europeans is still unclear, though.

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus