Our mixed-up human family: 8 human relatives that went extinct (and 1 that didn't)

Modern humans are far from the only species in the Homo genus. Here are others that went extinct long ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The ancient human family tree is complicated. An evolutionary trajectory that was once presented as a straight line has been abandoned, and our history is envisioned as a "muddy delta" or "braided stream" representing the interplay between physical and cultural adaptations across species. The story of the Homo genus is a saga that spans more than 2 million years and at least three continents, demonstrating our ancestors' ability to adapt to nearly any environment.

Related: Did art exist before modern humans? New discoveries raise big questions.

Africa

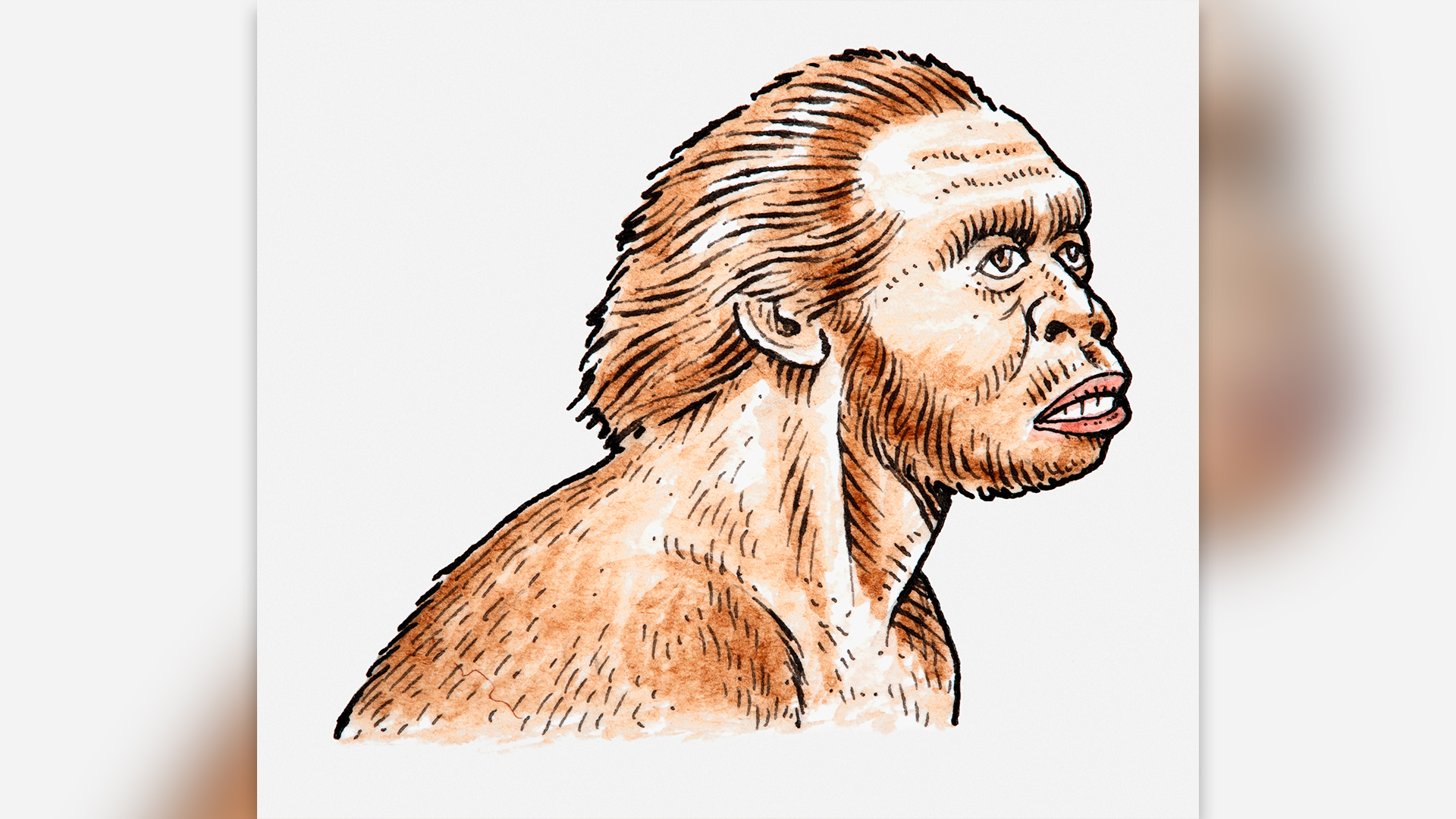

Homo habilis

Named "handyman" in 1964 because of stone tools found with its remains, Homo habilis flourished in Eastern and Southern Africa from 2.4 million to 1.4 million years ago. With a slightly larger brain than older human relatives' and an ape-like face, H. habilis stood about 4 feet (1.2 meters) tall, on average, and ate a fairly omnivorous diet. H. habilis was long assumed to be the earliest ancestral member of our genus, but this characterization is being questioned as new dating techniques have shown that H. erectus is even older than previously thought and perhaps unrelated to H. habilis.

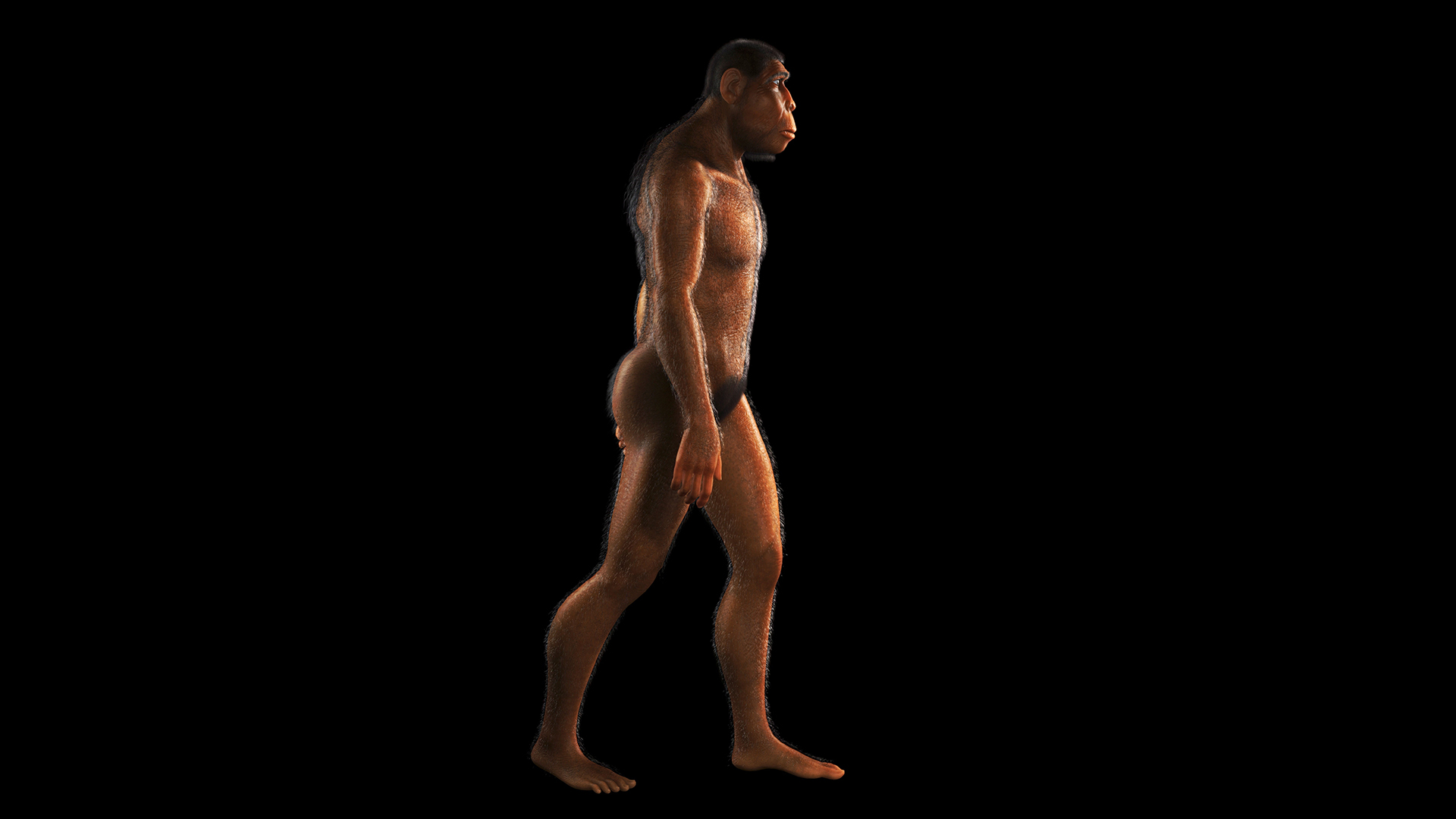

Homo erectus

This wildly successful species, known both as Homo erectus and Homo ergaster, originated at least 2 million years ago and survived until 110,000 years ago. As the earliest species to have human-like body proportions — the tallest of them reaching 6 feet (1.8 m) and 150 pounds (68 kilograms) — H. erectus needed a lot of energy to power both its body and its large brain. H. erectus developed specialized tools, figured out how to make fire to cook meat, and began exploring the world, leaving Africa and reaching as far as East Asia before either disappearing or evolving into other species.

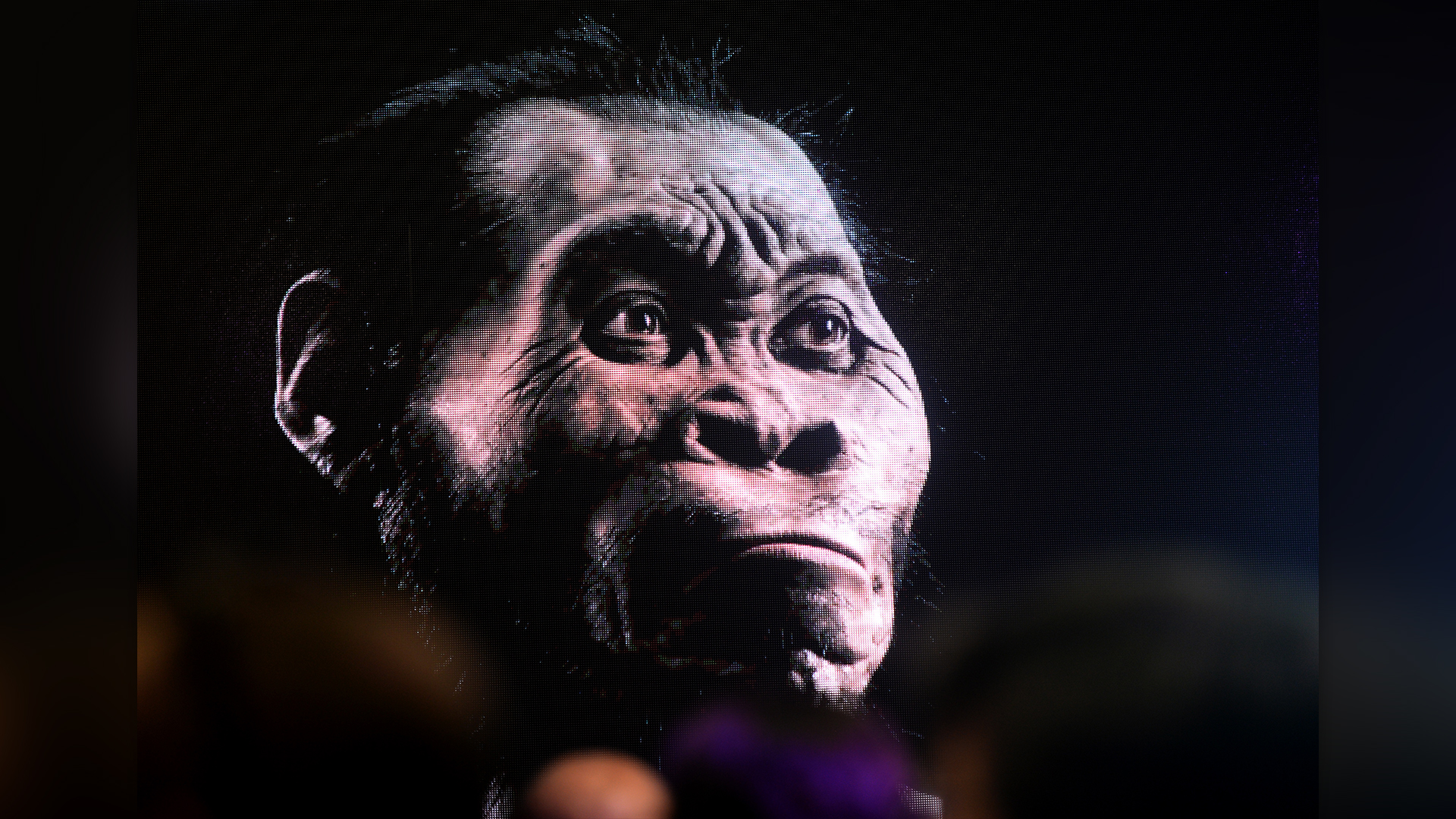

Homo naledi

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Discovered in a South African cave system in 2013, Homo naledi is one of the more mysterious members of our genus. Dating back to around 335,000 to 236,000 years ago, H. naledi walked on two feet but was also well adapted for climbing trees. At about 4 feet, 9 inches (1.4 m) and 88 pounds (40 kg), H. naledi was a petite, small-brained hominin. Without evidence of stone tools or other culture, little is known about H. naledi's lifestyle, although researchers have controversially suggested that they buried their dead and made cave art. It is unclear where, exactly, H. naledi fits in the Homo family tree.

Europe and Asia

Homo heidelbergensis

Likely evolving from H. erectus in Africa, Homo heidelbergensis was the first hominin to settle in colder climates, including in Europe. Living around 700,000 to 200,000 years ago, these hominins probably looked similar to their ancestor and used their big brains to create early shelters, hunt large animals and perhaps even ritually bury their dead. DNA evidence suggests that Neanderthals and modern humans diverged from a common ancestor and points to H. heidelbergensis as the species that led to our own.

Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals evolved from H. heidelbergensis around 400,000 years ago, according to the most recent research. Closely related to us, Neanderthals had an even more sophisticated culture, which included stone tools and perhaps cave art, than their ancestors. They looked like a slightly shorter, slightly stockier version of humans, with a larger midface region, all of which made them well adapted for survival in the cold climates of Europe and Western Asia. The cause of Neanderthals' extinction has been debated for decades, but DNA research has revealed that they definitely interbred with modern humans and that many of us carry Neanderthal genes. For this reason, some researchers think Neanderthals should be in the category of Homo sapiens with us.

Related: 13 of the world's oldest artworks, some crafted by extinct human relatives

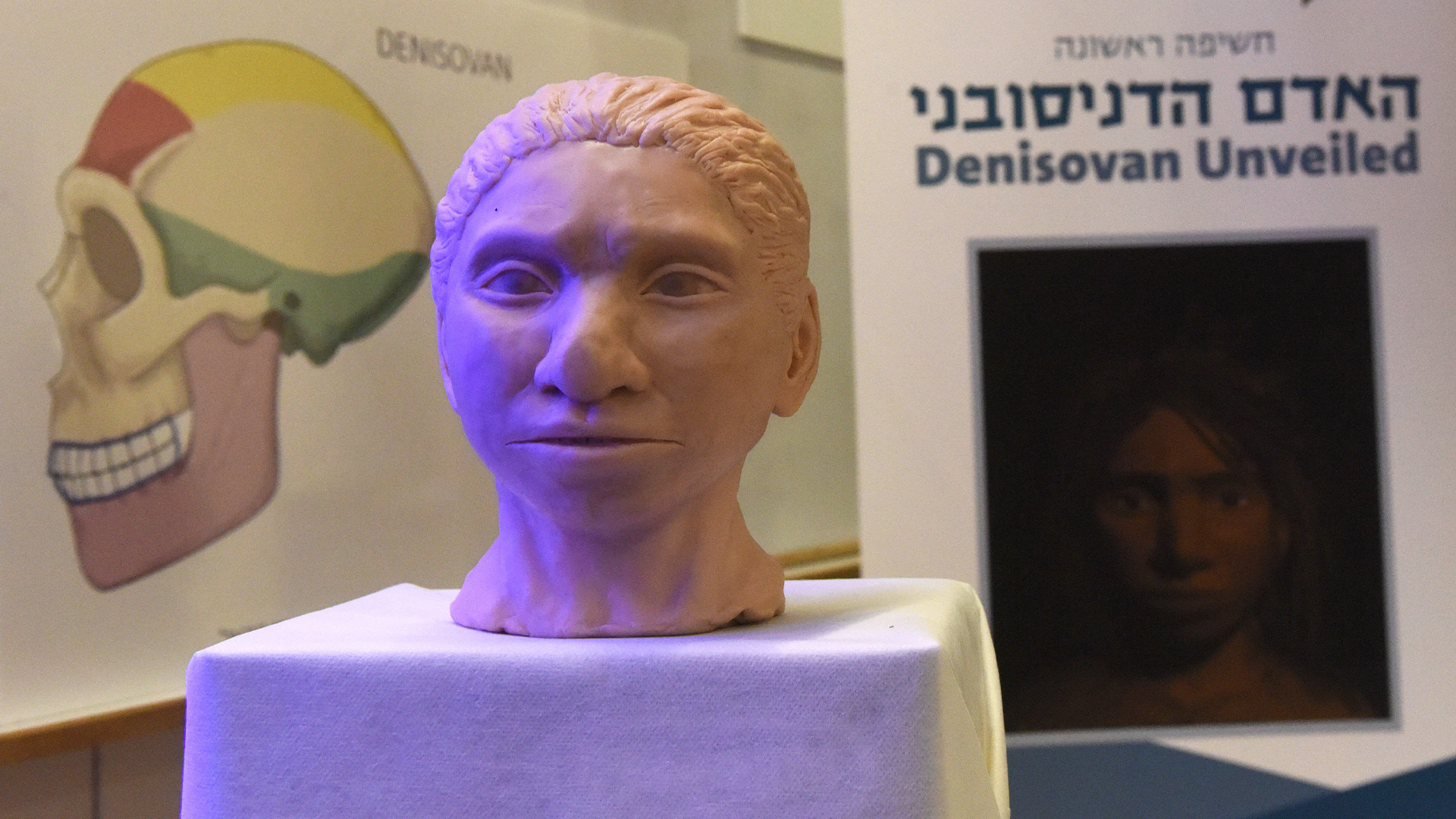

Denisovans

When a small handful of fossils were discovered in a Siberian cave in 2010, identification of the exact species was unclear. Dating from 194,000 to 51,000 years ago, the Denisova hominins are enigmatic, and the only real information about them has come through DNA analysis. Scientists know that Denisovans were closely related to both Neanderthals and modern humans, as there is evidence of interbreeding, particularly with early humans in Southeast Asia. Currently, there is not enough fossil material for the Denisovans to warrant their own species name. But since some of their genes have been found in modern humans, they — like Neanderthals — could even be considered part of our own species. Regardless of what we call them, it is clear they are part of the Homo genus.

Pacific Islands

Homo floresiensis

As research progresses on Denisovans and hominin fossils in Southeast Asia, the position of other species in the Homo family tree may become clear. In 2003, specimens of a very small hominin were discovered in a cave on the island of Flores in Indonesia. Found with stone tools, H. floresiensis lived between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago. Even though they stood only around 3 feet, 6 inches (1 m) tall, the members of this species otherwise look a lot like H. erectus. The current hypothesis is that they descended from H. erectus and evolved to have small bodies due to insular dwarfism, an evolutionary adaptation to the lack of resources on the island. Because of their size, H. floresiensis members are often referred to as "hobbits."

Homo luzonensis

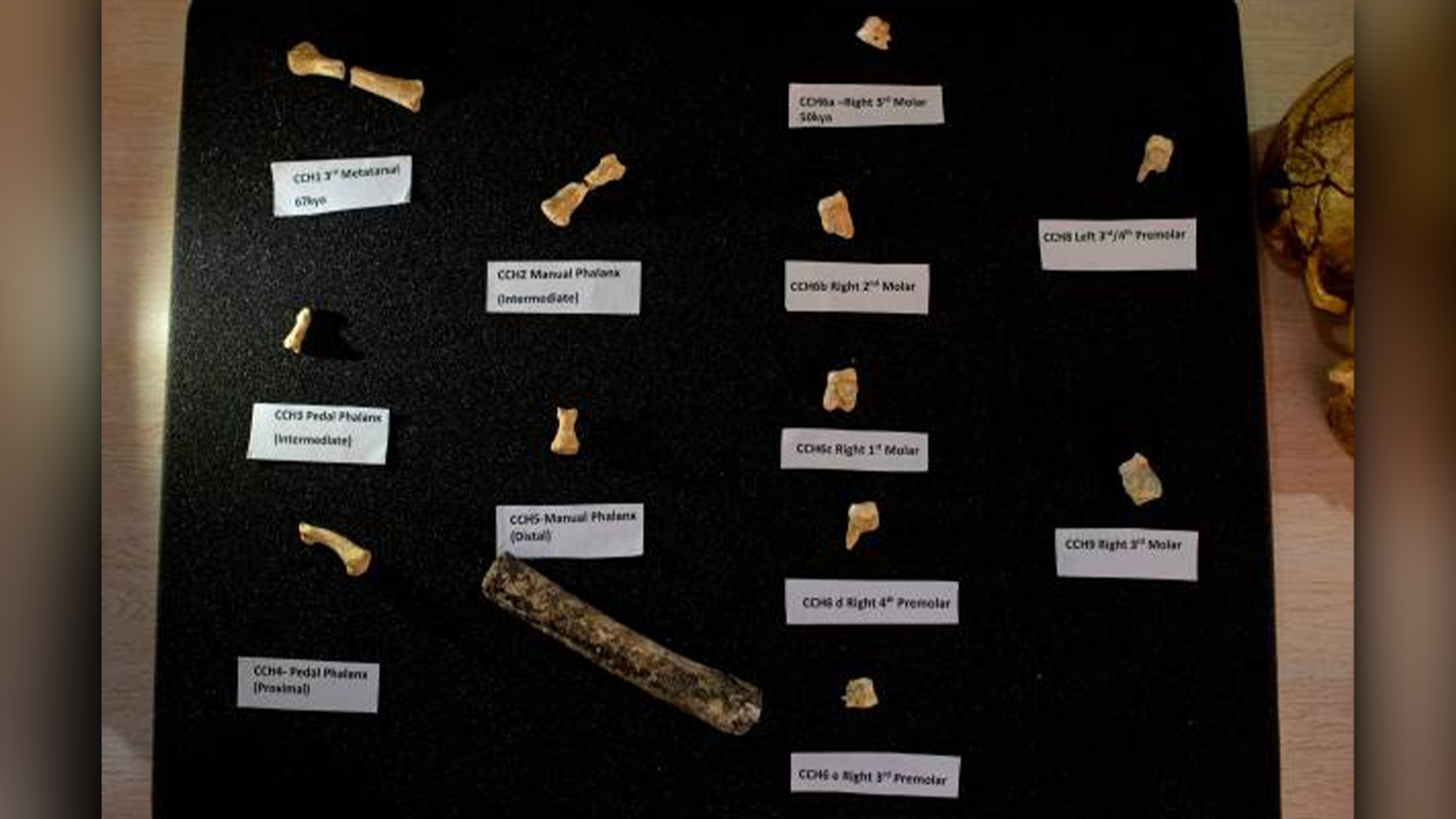

A second species of small hominins was named in 2019 after the discovery of a dozen fossils on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. With longer fingers and toes than modern humans' and distinct teeth, it is unclear where, exactly, H. luzonensis sits in the Homo genus. The fossil bones date to 67,000 years ago, which shows that early hominins knew how to make open-sea crossings, but Luzon has also produced dozens of stone tools and butchered rhinoceros bones that provide circumstantial evidence that a hominin ancestor was living there as far back as 709,000 years ago.

Everywhere

Homo sapiens

Modern humans, Homo sapiens, seem to have appeared in Africa at least 300,000 years ago, likely due to the ability to adapt to an unstable and quickly changing environment. Our species has a slimmer build than our ancestors did, as well as a very large brain contained in a round skull with a high, flat forehead. H. sapiens has survived by spreading throughout the world, adapting to environments ranging from hot, humid jungles to cold, arid tundras, mainly through cultural, rather than physical, adaptations. But our story isn't over yet, as we haven't stopped evolving — we've gotten better at fighting off certain pathogens, for example — and many researchers have shown that, in fact, the recent genetic evolution of our species has been extraordinarily rapid.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus