8 times fossilized human poop dropped big knowledge on us. (Number 2 will surprise you.)

Here's the scoop on ancient human poop.

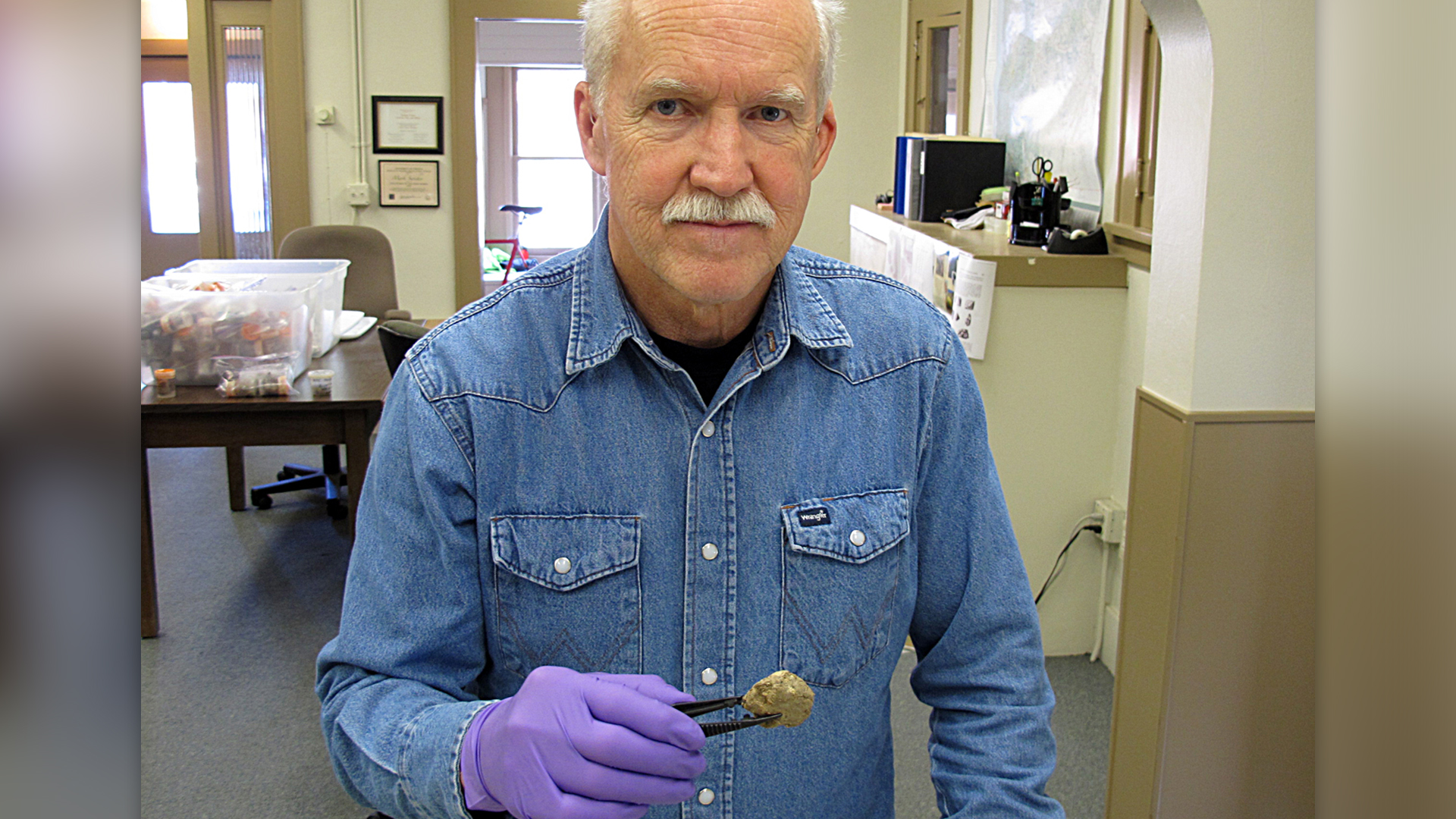

Everybody poops, but only some of that poop fossilizes, turning into coprolites. While ancient droppings may sound gross — after all, who wants to go digging through feces that are centuries or even millennia old — they can offer a cornucopia of data to scientists.

For instance, coprolites can reveal which foods people ate, the parasites that lived in their guts and even prove that humans lived in an area, like North America during the last ice age, according to coprolites found in a cave in Oregon.

Here are eight times human coprolites dropped knowledge on modern scientists.

Related: 10 amazing things we learned about our human ancestors in 2022

1. Parasites galore

Human poop found in old latrines reveals that gut parasites were rampant in the ancient world. For example, biblical-era toilets in Jerusalem had excrement with protozoa that caused "traveler's diarrhea"; human waste from the Roman Empire had whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides) and Entamoeba histolytica, which can cause dysentery; and 800-year-old Crusader poop from Cyprus was teeming with whipworms and roundworms.

These unsavory hitchhikers reveal that people in these times likely ate undercooked meat, such as the uncooked and fermented fish sauce known as garum that was popular in Roman times. Or, perhaps these parasites spread through bad sanitation practices, such as contaminated water or a lack of hand washing.

2. Ancient humans in Oregon

For nearly a century, researchers thought that the first humans in the Americas were the Clovis, a group that arrived in North America shortly before 13,000 years ago. But in recent decades, researchers have found evidence indicating that humans arrived thousands of years earlier. One of those findings, of human coprolites in Oregon's Paisley Caves, shows that people were in what is now the United States by 14,500 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the study came out in 2012, these fossilized feces were the "oldest directly dated human remains (DNA) in the Western Hemisphere," the researchers wrote in the journal Science.

3. Stonehenge-era builders ate parasite-infested meat

Neolithic construction workers left behind more than just stone structures. At Durrington Walls, a Neolithic settlement about 1.7 miles (2.8 kilometers) from Stonehenge in England, researchers found fossilized clusters of human poop, suggesting that these builders had epic winter feasts in which workers and their dogs chowed down on undercooked meat rife with the eggs of parasitic worms.

"This is the first time intestinal parasites have been recovered from Neolithic Britain, and to find them in the environment of Stonehenge is really something," study lead researcher Piers Mitchell, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., said in a statement.

4. Disappearing high-fiber diets

The Indigenous people of the American Southwest used to eat high-fiber foods such as prickly pear, yucca and flour ground from plant seeds, according to an analysis of fossilized feces from A.D. 1150 and earlier. This diet was 20 to 30 times more fibrous than a typical modern diet, a 2012 study found. The rapid change from high-fiber to low-fiber processed foods prevalent in modern diets may explain why many Indigenous people have type 2 diabetes today.

"When we look at Native American dietary change within the 20th century, the more ancient traditions disappeared," study researcher Karl Reinhard, an environmental archaeologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, previously told Live Science. "They were introduced to a whole new spectrum of foods like fry-bread, which has got a super-high glycemic index."

5. Arctic archipelago poop

Sometimes you don't find a coprolite, but the chemicals leftover from human waste. That was the case for researchers investigating periods of human occupation in the Lofoten Islands, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Circle. The team took several sediment cores so they could look for chemical components of human and livestock waste. They also looked for chemical footprints of burned vegetation.

According to these chemicals, people and animals came to the area around 2,300 years ago and burned vegetation, likely to clear forests to make way for farming and grazing land. But poop output decreased around the time that Iceland was discovered, likely because people decided to migrate there. Poop levels also dropped when plague hit the region. When the Little Ice Age hit (circa 1300 to 1850), poop chemicals stayed constant while burned vegetation signatures increased, likely because settlers were stoking fires to stay warm.

6. Our Mesolithic ancestors were cannibals

In case you needed proof that Middle Stone Age, or Mesolithic humans were cannibals, look no further than their coprolites. Bits of human bones were found in human poop from 9,000 to 10,200 years ago deep in a cave in Alicante, Spain. Some bones had bite, cut and scrape marks, the researchers found. However, it's unknown if these people were eaten during rituals or because the cannibals were starving.

7. People ate cotton

Ancient DNA from 1,500-year-old coprolites in the Caribbean revealed foods favored by pre-Columbian cultures. Two groups in Puerto Rico, the Huecoid and Saladoid, used to eat an array of foods, including maize, sweet potato, chili peppers, peanuts, papaya, tomato and, unexpectedly, cotton and tobacco, according to fecal analyses. It's possible that cotton seeds or oil were consumed, but cotton oils are bitter, according to the researchers, who published their 2023 findings in the journal PLOS One. So another possibility is that Indigenous women who wove with cotton fibers used their saliva to prepare the raw yarn, the team noted.

These cultures may have also chowed down on a "variety of dietary, medicinal, and hallucinogenic plants," the researchers wrote in their 2023 study, published in the journal PLOS One.

8. Ancient hyenas ate humans

Coprolites from ancient hyenas and their bite marks on bones reveal that humans were on the menu for these carnivores up to 4,500 years ago in Saudi Arabia. The hyenas took up residence in a lava-tube cavern for several millennia, leaving behind piles of old bones, including those of humans.

It's unclear if the hyenas had killed or scavenged their human prey. Other bones in the lava tubes included those from donkeys, caprines (a type of goat), gazelles, camels and wolves or dogs.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus