Stonehenge builders ate parasite-infested meat during ancient feasts, according to their poop

The builders also fed the worm-infested meat to their dogs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In addition to a Neolithic monument, the builders of Stonehenge left behind something a little less celebratory: fossilized clumps of poop. A new analysis of these so-called coprolites suggests that during epic winter feasts, the ancient workers and their dogs ate undercooked meat littered with the eggs of parasitic worms.

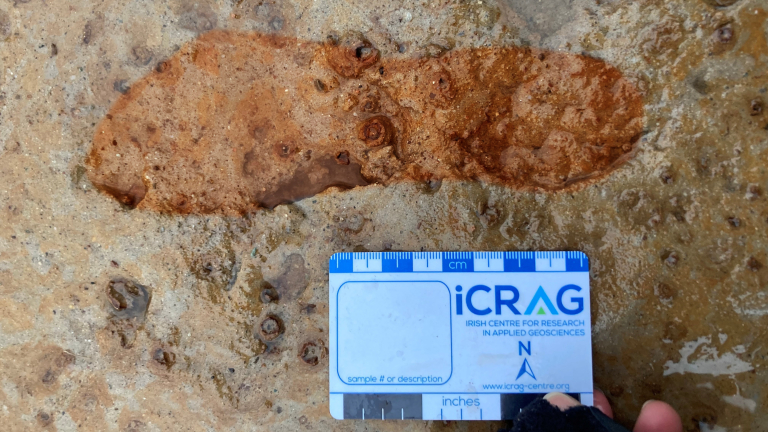

The team of researchers uncovered the fossilized "poop balls" in a refuse heap at Durrington Walls — a Neolithic settlement situated around 1.7 miles (2.8 kilometers) from Stonehenge. Experts believe that the site would have been home to many of the workers who built the iconic rings of standing stones, which may have acted as a solar calendar, between 4,000 and 5,000 years ago, according to a statement by the researchers.

Researchers analyzed 19 coprolites found at the site, originating from both humans and dogs, and they found that five of the samples (four from dogs and one from a human) contained the eggs of various parasitic worms. The team thinks that a majority of the parasite eggs were served to the Neolithic builders in undercooked meat dishes enjoyed at large winter feasts, the leftovers of which were likely fed to the dogs. This is the oldest evidence of parasitic worms in the U.K. that can also be traced back to their original source, according to the statement.

"This is the first time intestinal parasites have been recovered from Neolithic Britain, and to find them in the environment of Stonehenge is really something," study lead researcher Piers Mitchell, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., said in the statement.

Related: 'Wonderfully-shaped feces' found inside ancient fish skull. What left the pretty poops?

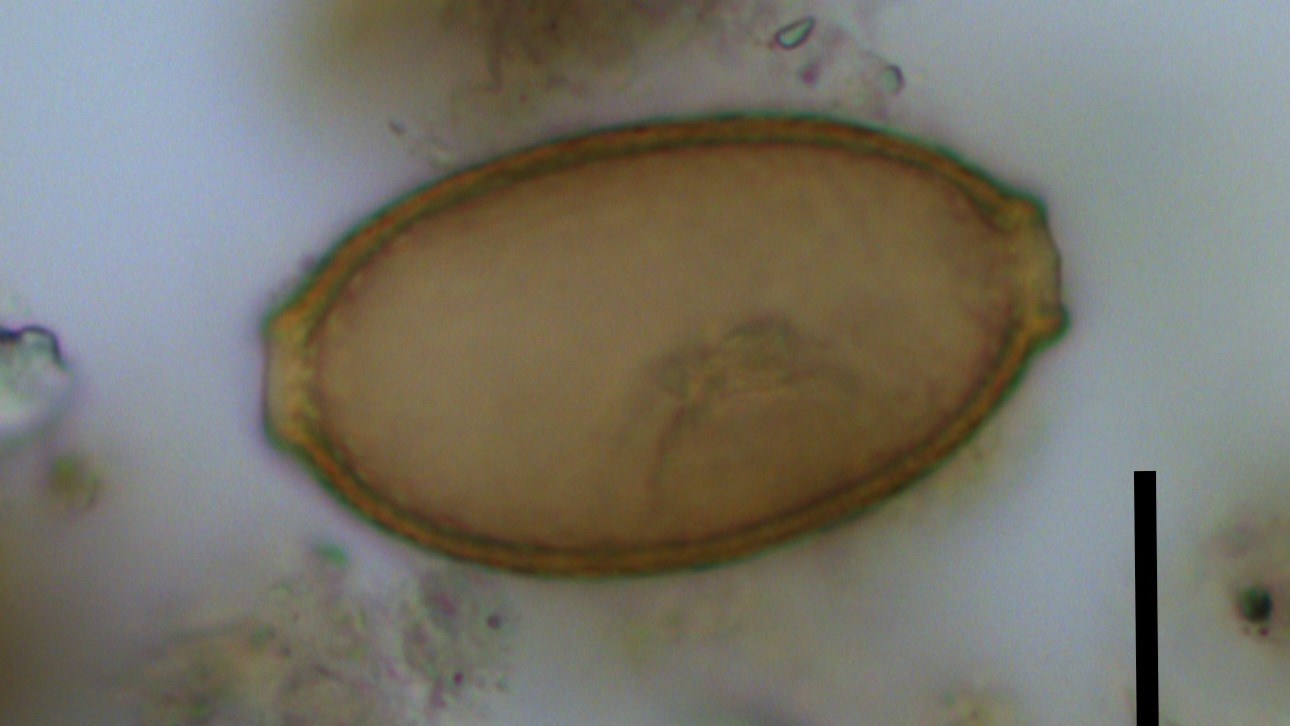

Four of the five contaminated samples, including the human excrement, contained lemon-shaped eggs belonging to unknown species of capillariid worms, a type of parasitic worm that grows within the internal organs of several animals including rodents, monkeys and livestock such as cows, sheep and pigs.

Capillariid worms have an unusual life cycle that involves at least two other animals. First, the worms infect animals — such as rats — that accidentally ingest the eggs from their environment. The eggs then attach to the animal's internal organs, such as the liver, lungs and intestines. The eggs hatch and as the worms grow, they start to devour the organs before eventually reproducing asexually to produce more eggs. The infected animals are then predated upon by larger predators and the eggs are passed through the predator's digestive tract before being excreted back into the environment to be ingested by another host.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Modern humans are known to be infected by two species of capillariid worms: Capillaria hepatica and Capillaria philippinensis. When these worms begin to devour a person's organs, the disease is called capillariasis, and it can be fatal if not treated properly, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, in this case, the Stonehenge builders and their dogs were likely not infected by the worms. If they had been infected, the eggs would not have made it into their stool because they would have settled in their internal organs and hatched. Instead, they likely ate meat from an infected animal and passed on the eggs much like a predator would in the wild, according to the statement.

"The type of parasites we found are compatible with previous evidence for winter feasting on animals during the building of Stonehenge," Mitchell said. Feasts were more common in winter because that was when a majority of workers traveled to Stonehenge: During the rest of the year, they returned home elsewhere in the U.K. and building work slowed down, according to the statement.

The builders likely acquired the eggs after eating offal, the intestines and other internal organs, from cattle, the researchers suspect. Previous studies have shown that builders may have herded cattle more than 62 miles (100 km) to be consumed at these feasts, and capillarid eggs can infect cattle and other ruminants, according to the statement.

Offal is not eaten widely today (although it is still common among some Asian cultures), but was a popular food among Neolithic communities, according to the statement.

This particular offal may have been undercooked. "Pork and beef were spit-roasted or boiled in clay pots, but it looks as if the offal wasn't always so well cooked," study co-author Mike Parker Pearson, an archaeologist at University College London in the U.K., said in the statement.

In 2021, another study from the Durrington Walls site revealed that the ancient builders also ate 'energy bars' made from berries, fruit and meat.

The final dog coprolite contained eggs of a tapeworm, most likely Dibothriocephalus dendriticus, which is normally found in freshwater fish. Since there is no evidence that fish was consumed at the Durrington Walls feasts, the researchers suspect that this dog likely ate an infected fish before the builders traveled to Stonehenge for the winter.

The study was published online May 18 in the journal Parasitology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus