Nom Nom Nom: Prehistoric Human Bones Show Signs of Cannibalism

Human cannibals likely took a big bite out of their fellow humans about 10,000 years ago, according to a study that examined prehistoric bones with scratch and bite marks on them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Human cannibals likely took a big bite out of their fellow humans about 10,000 years ago, according to a study that examined prehistoric bones with scratch and bite marks on them.

The bones, discovered in the Santa Maria Caves (Coves de Santa Maria) in Alicante, Spain, may be the first instance of cannibalism in the western European Mediterranean region dating to the Mesolithic period, the researchers said. (The Mesolithic period last from about 10,200 to 8,000 years ago on the Iberian Peninsula. "Mesolithic" means middle stone, and it's between the Paleolithic, or old stone, and Neolithic, or new stone, periods.)

The human bones were an accidental find, said study lead researcher Juan Morales-Pérez, a researcher in the Department of Prehistory, Archeology and Ancient History at the University of Valencia in Spain. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

"I was studying the remains of Mesolithic animals from the Santa Maria site, and suddenly I identified a human distal humerus — an elbow — and it was full of cuts," Morales-Pérez wrote in an email to Live Science.

He quickly told his thesis director, "Emili, we have a man here!" before searching for more bones, Morales-Pérez said. In the end, they discovered 30 bones belonging to three individuals: a robust adult, a gracile adult and an infant. However, the infant had only one complete bone (a shoulder blade, or scapula) that did not show signs of cannibalism, the researchers said.

The bones date to between 10,200 and 9,000 years ago, Morales-Pérez said. The last of the hunter-gatherer communities lived during this time, and evidence suggests that their culture was more organized and complex than it was during the Paleolithic period.

"A good example [of this complexity] is the appearance of the first cemeteries," Morales-Pérez said. "There are also these strange examples of cannibalism."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, there's evidence of human cannibalism in northwestern Europe that dates to the Mesolithic, he said. But the practice goes way back: there's even evidence of Neanderthal cannibalism in Belgium and Spain from more than 40,000 years ago, when they went extinct, Live Science previously reported.

Tooth marks

Morales-Pérez and his colleagues wanted to be certain that the bones showed evidence of human cannibalism, not just signs that a carnivore had been gnawing on human bones.

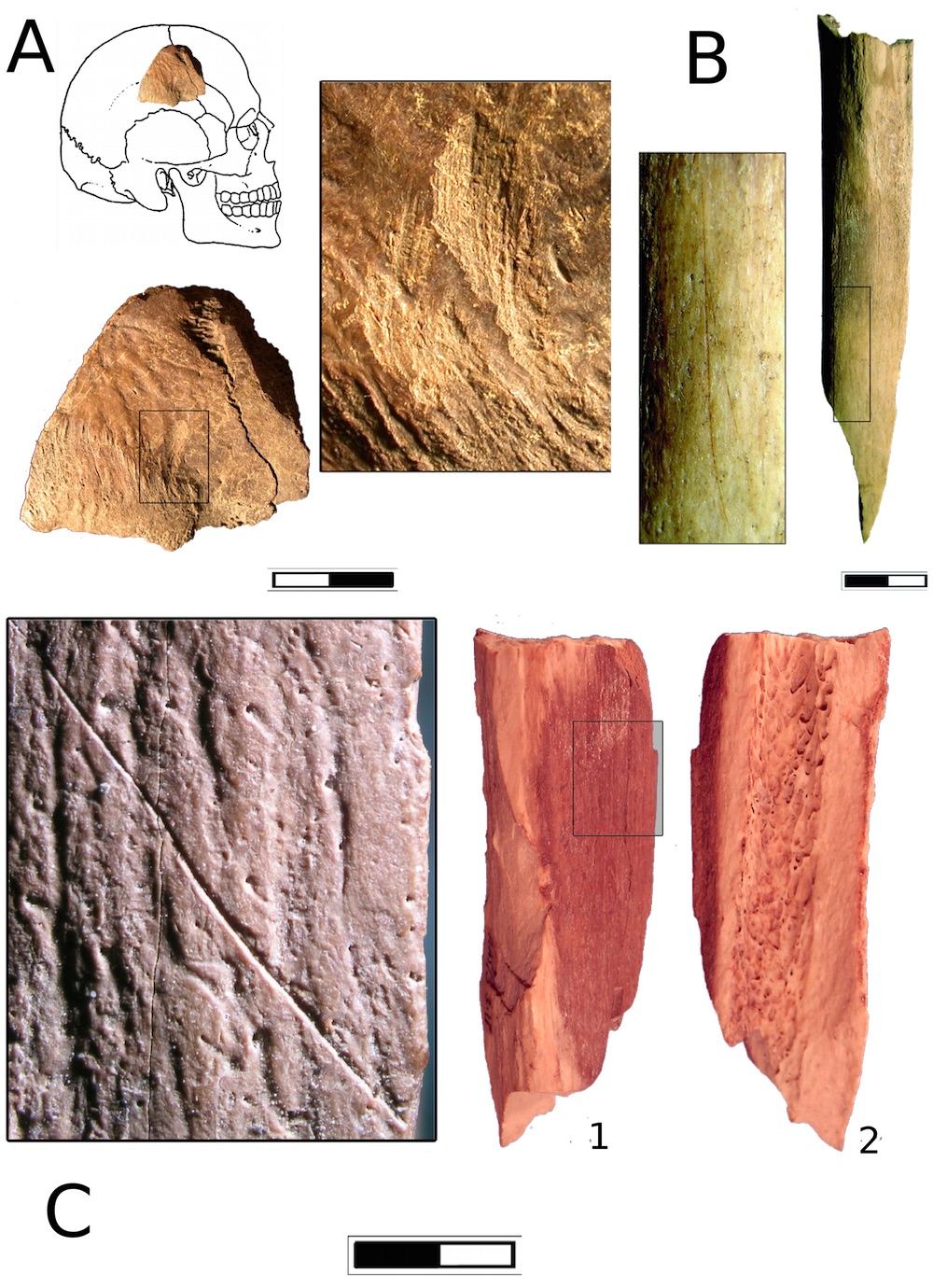

"Distinguishing bite marks made by different carnivores and omnivores — including humans — is a complicated task," the researchers wrote in the study. "However, when the marks result from human biting and gnawing, the intensity of the bite is normally lower and there are no scratches or pit marks, while bones affected by carnivores present clear, intensive tooth marks."

To be sure, the researchers compared the bite marks in the prehistoric bones to human bite marks on modern-day rabbit bones, and found that the marks were similar in shape. Moreover, they found human bones within human coprolites (mummified human poop) within the cave, the researchers said.

Eight of the bones, including a skull fragment, had stone-made cut and scrape marks. These marks were likely made to cut through ligaments and deflesh the muscles from the bones, according to the scientists. What's more, 19 of the bones had burn marks on them that were likely made after the meat was removed but before they were broken, the researchers said.

However, it's unclear if this cannibalism was performed because of hunger or rather some kind of ritual. For instance, these marks could have resulted from violence, war, funeral rituals or supernatural beliefs, the researchers said.

"It was a fantastic find, and very curious," Morales-Pérez said.

The study was published in the March issue of the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus