'It was probably some kind of an ambush': 17,000 years ago, a man died in a projectile weapon attack in what is now Italy

A new analysis of a skeleton uncovered 50 years ago provides some of the earliest evidence of intergroup conflict between humans to date.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Around 17,000 years ago, a man fell victim to a bloody ambush in what is now Italy, with an enemy launching sharp, flint-tipped projectiles that left gashes on his thigh and shin bones, a new study finds.

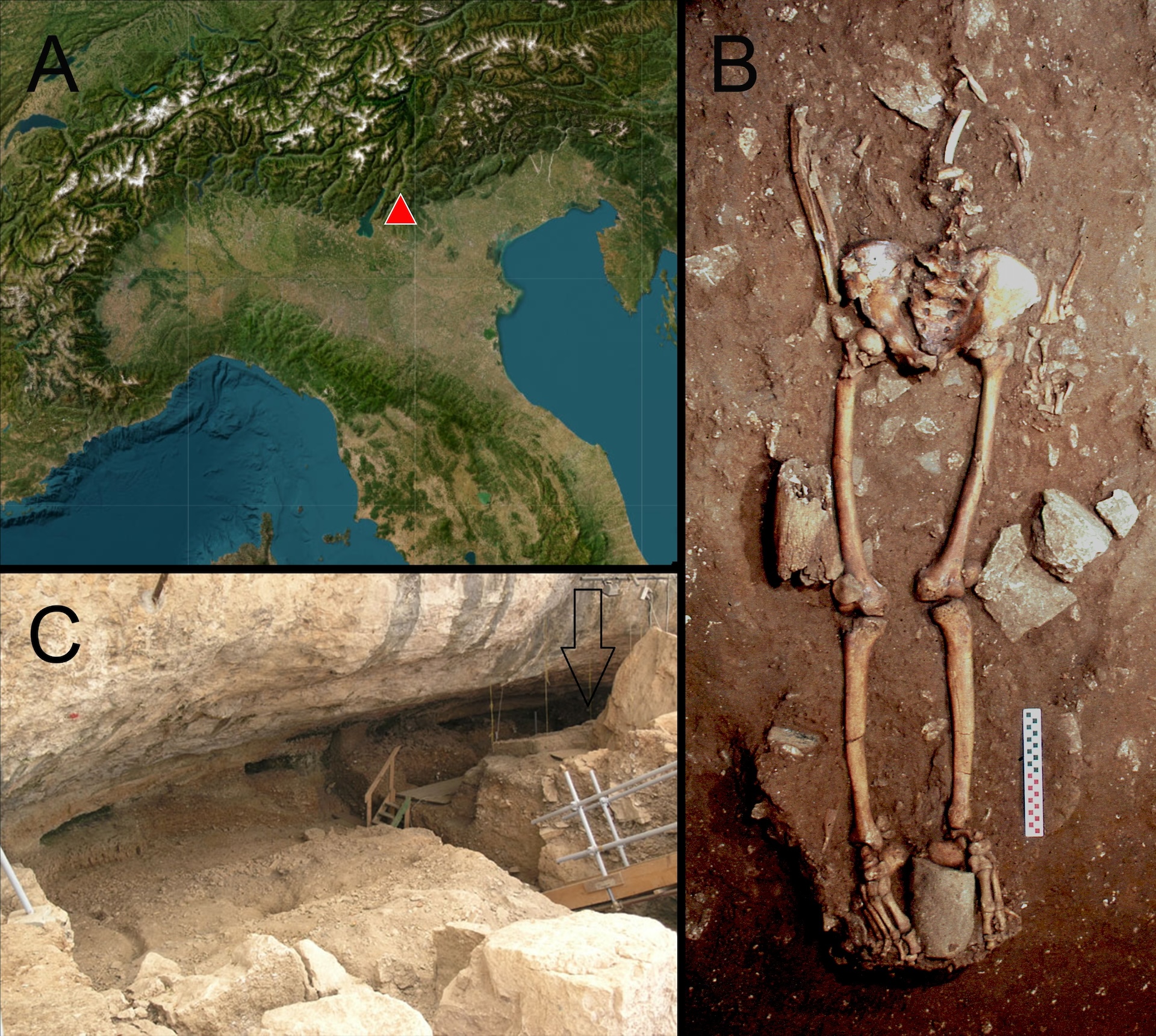

Researchers have known about this man, called Tagliente 1, since 1973, when his remains were uncovered during excavations at the Riparo Tagliente rock shelter in northeastern Italy. But the circumstances around his death had been a mystery. Now, a new discovery of cut marks on his leg bones reveals that this hunter-gatherer had a violent death, researchers reported in the study, which was published on April 28 in the journal Scientific Reports.

The finding is some of the earliest evidence of "projectile impact marks" in the human paleobiological record, the researchers wrote in the study.

When Tagliente 1 was first unearthed, disturbances during the dig led to the recovery of only his lower limbs and fragments of his upper body. But he is known to have lived during the Late Epigravettian period (circa 17,000 to 14,500 years ago), just after the Last Glacial Maximum, the coldest part of the last ice age.

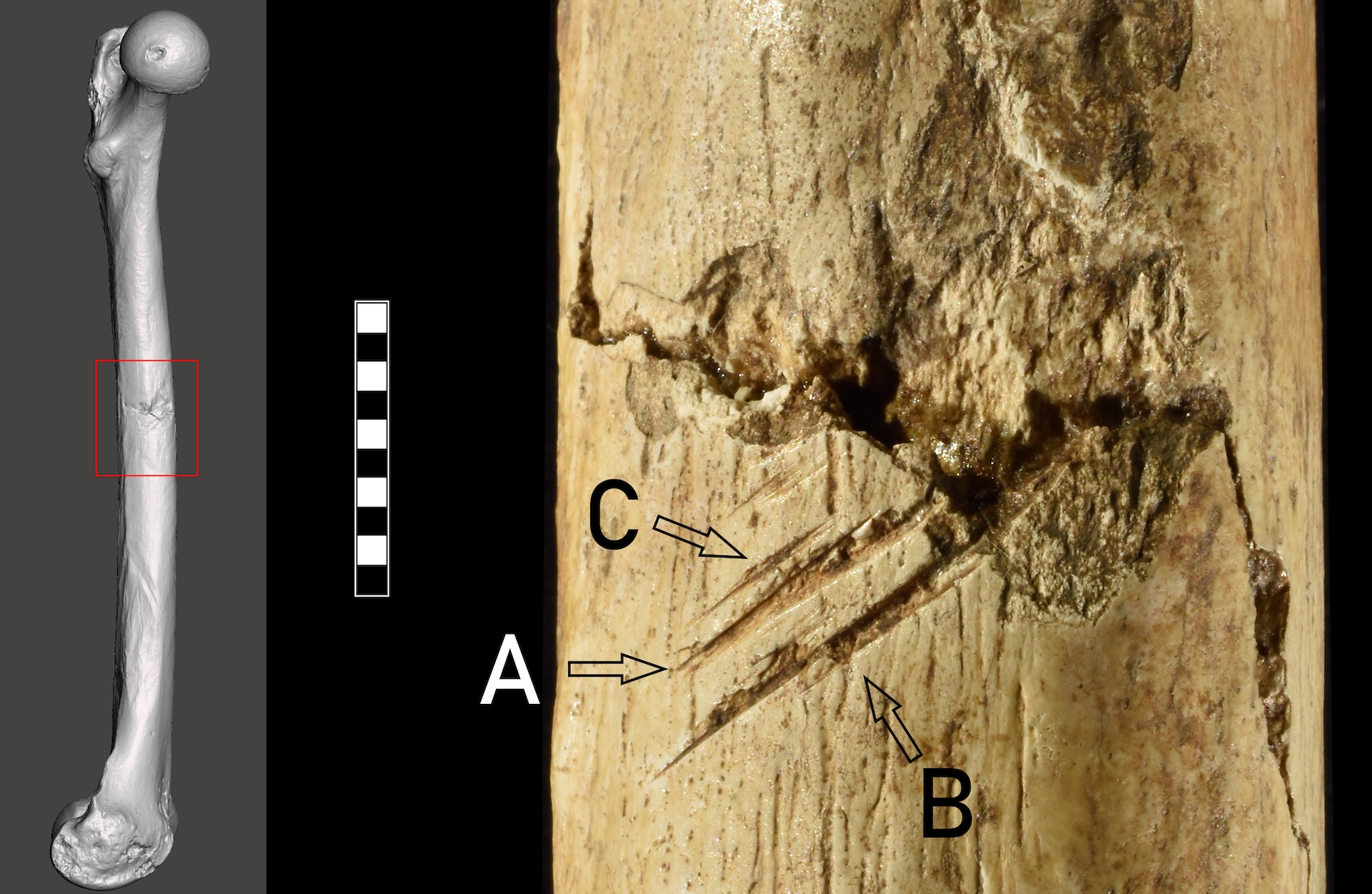

To learn more about Tagliente 1, who died between the ages of 22 and 30 according to a 2024 analysis of his leg bones, pelvis and teeth, Vitale Sparacello, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Cagliari in Italy and a co-author of the new study, took a deeper look at the Stone Age man's remains. While analyzing 3D images of Tagliente 1's bones, he noticed three parallel lines on the left femur, or thigh bone.

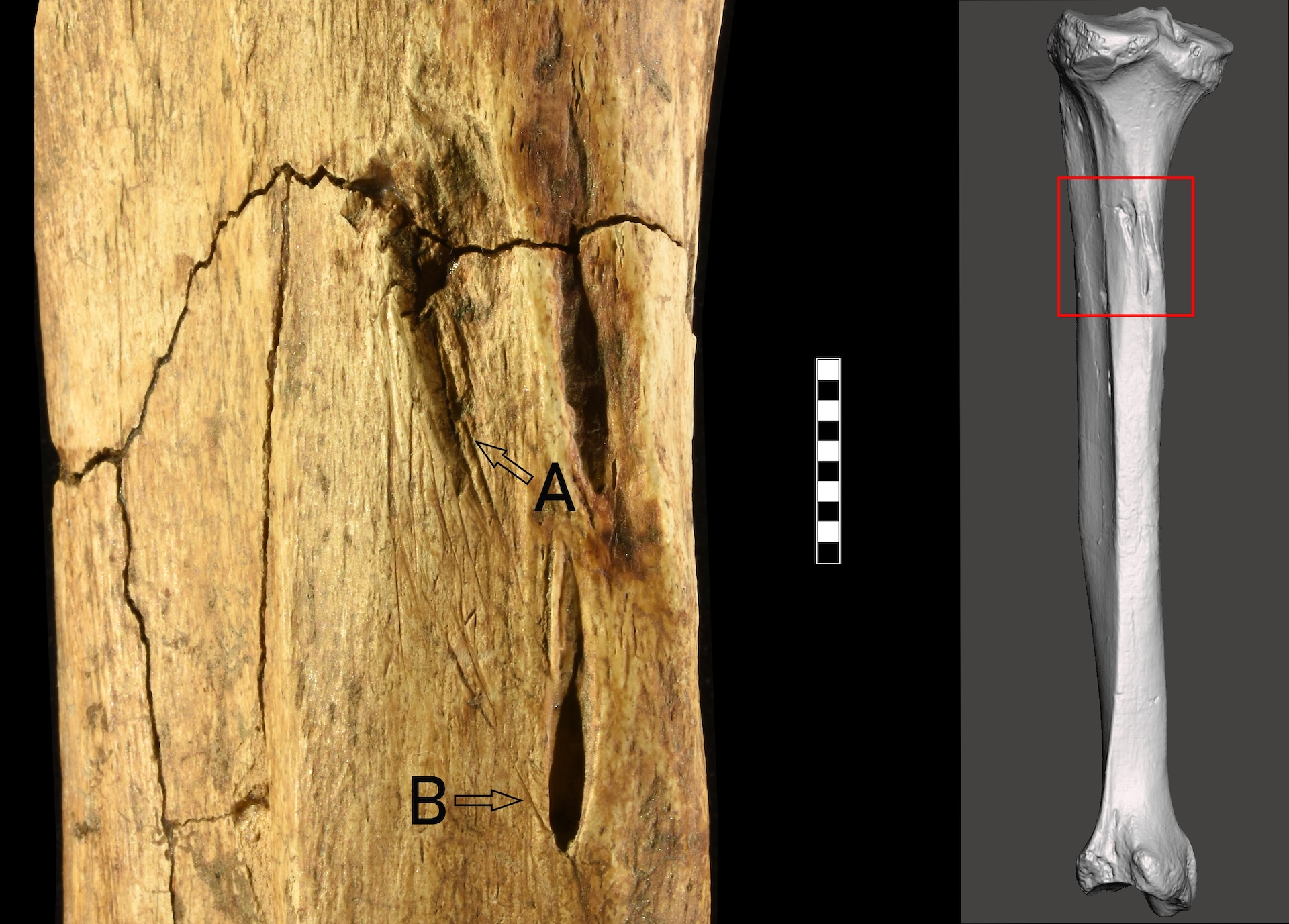

"My mind started running," Sparacello told Live Science. When his colleagues went to the Natural History Museum of Verona to inspect the bones themselves, they found two more marks on the tibia, or shinbone, he said.

Related: Stone Age Europeans mastered spear-throwers 10,000 years earlier than we thought, study suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Prehistoric projectiles

Traces of Paleolithic violence are rare, the researchers said, making new finds like Tagliente 1's remains valuable for piecing together the histories of past peoples.

After discovering five straight cuts on the left femur and tibia, the team used a scanning electron microscope to determine features such as the shape and depth of the grooves, which revealed that one side of each lesion was steeper than the other.

Then, the researchers compared Tagliente 1's lesions with those produced during previous experiments with exact replicas of different Late Epigravettian projectile weapons on wild sheep and goat carcasses. In that study, researchers examined the marks on the animal skeletons that were caused by flint-tipped arrows, and how they differed from those produced by carnivores or decay.

All analyses pointed toward four of the five lesions on Tagliente 1's bones resulting from flint-tipped projectile weapons that were thrown at high speeds. He was hit from the front and behind, suggesting that there were either multiple assailants or that he was struck while running away, the researchers found.

"Well, it could be an accident, but, like, what kind of accident is that?" Sparacello said. "So it was probably some kind of an ambush attack."

Stone Age violence

Tagliente 1's bones showed no sign of healing, which indicates that he died soon after the attack, the researchers noted. The lethal blow may have been where one projectile hit close to the femoral artery.

"It's very, very possible that this was a rapid death, because once your femoral artery is pierced, you have basically a few minutes before it's too late," Sparacello said.

It's impossible to know who attacked Tagliente 1, but previous research offers clues. A study published in the journal Nature in 2016 suggested that projectile weapons indicate intergroup conflict rather than other forms of violence, like personal rivalries. And while it's unknown what triggered the attack, the researchers have an idea: They think the violence was sparked because of climate change, with the receding glaciers opening up new territories and prompting competition for resources.

Stone Age quiz: What do you know about the Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic?

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus